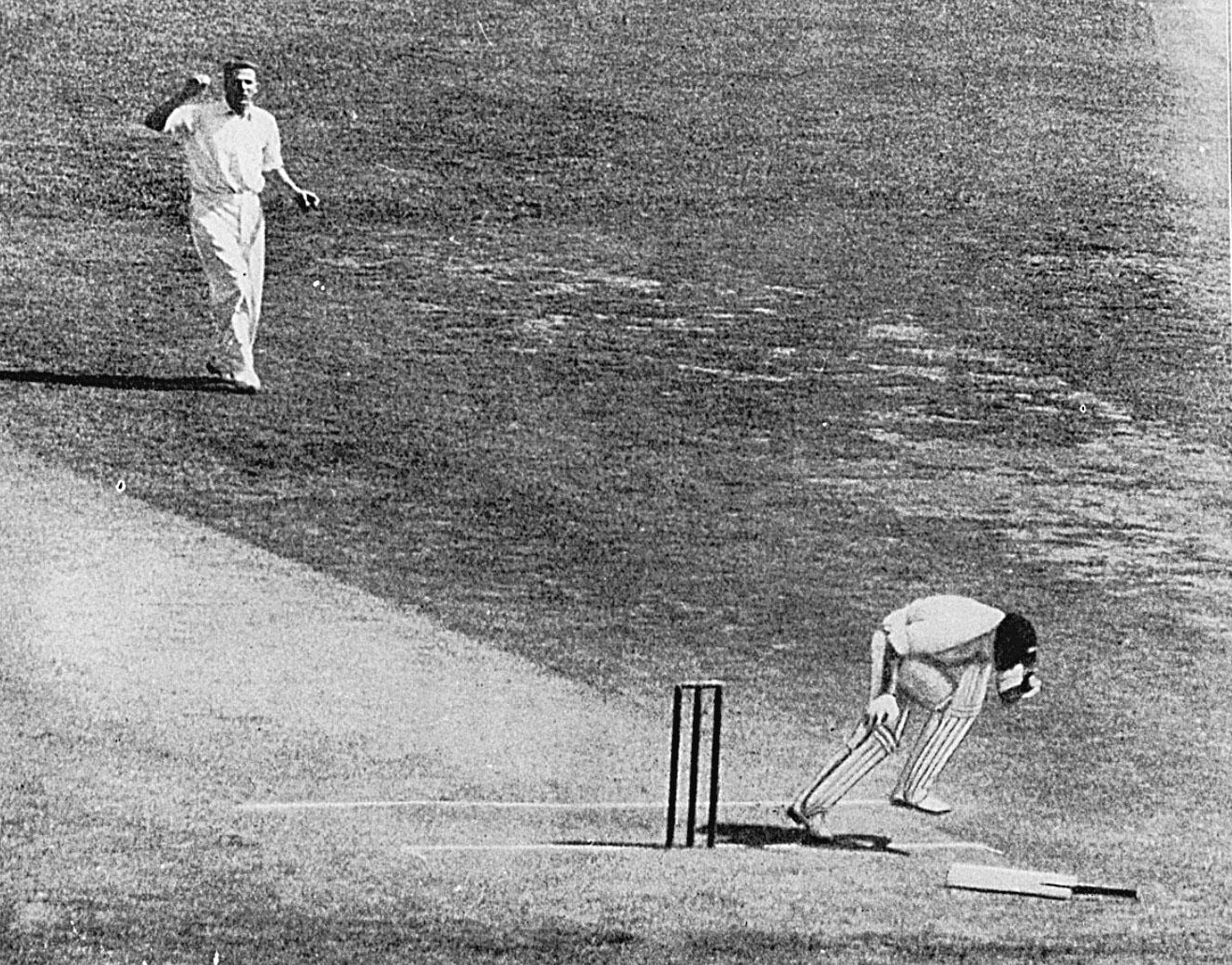

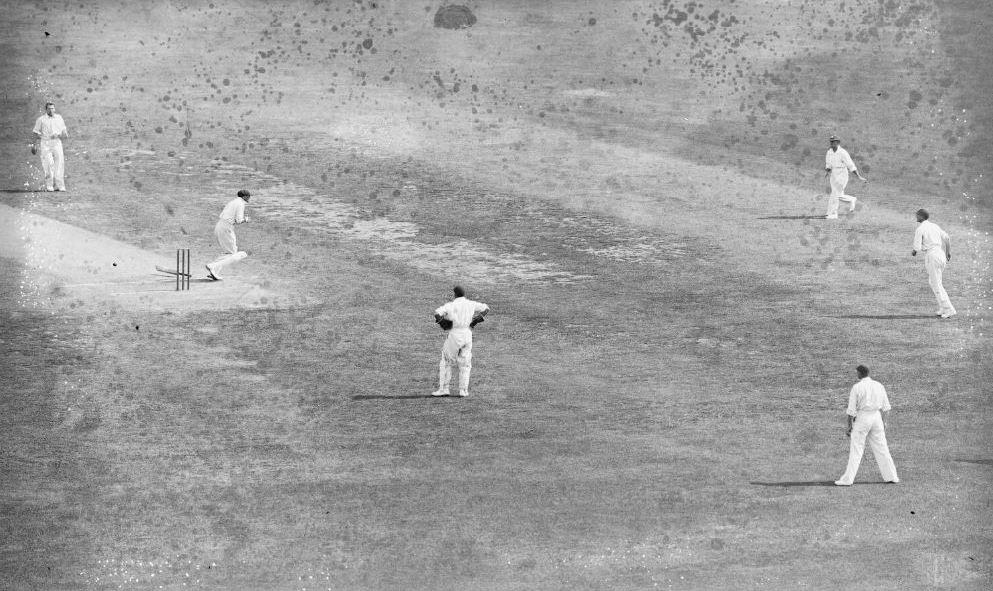

Two images burn brightest at the centre of the Bodyline controversy, the greatest flashpoint in Ashes history. One is of Bill Woodfull, Australia’s captain, clutching the area over his heart as his bat tumbles to the ground after he had been struck by a ball from Harold Larwood; the other is of team-mate Bert Oldfield staggering from the crease after top-edging a ball from Larwood into his skull. Both incidents occurred during the pivotal third Test of the 1932-33 series at the Adelaide Oval.

Conveying better than any words the impact of Douglas Jardine’s uncompromising tactics, they helped strengthen local opinion against the English team as soon as they appeared in Australian newspapers — although ironically they would never have been so graphic without the groundbreaking work of an English immigrant based in Sydney, Herbert Henry Fishwick.

A fierce Larwood delivery strikes Oldfield in the head at the Adelaide Oval in 1933

FAIRFAX MEDIA

Fishwick was born in Devon in 1882, the son of a master mariner, and in his twenties moved to Australia, where he quickly earned plaudits as an outdoor photographer. In the years after the First World War he had ordered equipment from London to develop a pioneering telescopic camera measuring 4ft in length, and astonished everyone with the close-up action shots he secured of the Ashes series in 1920-21.

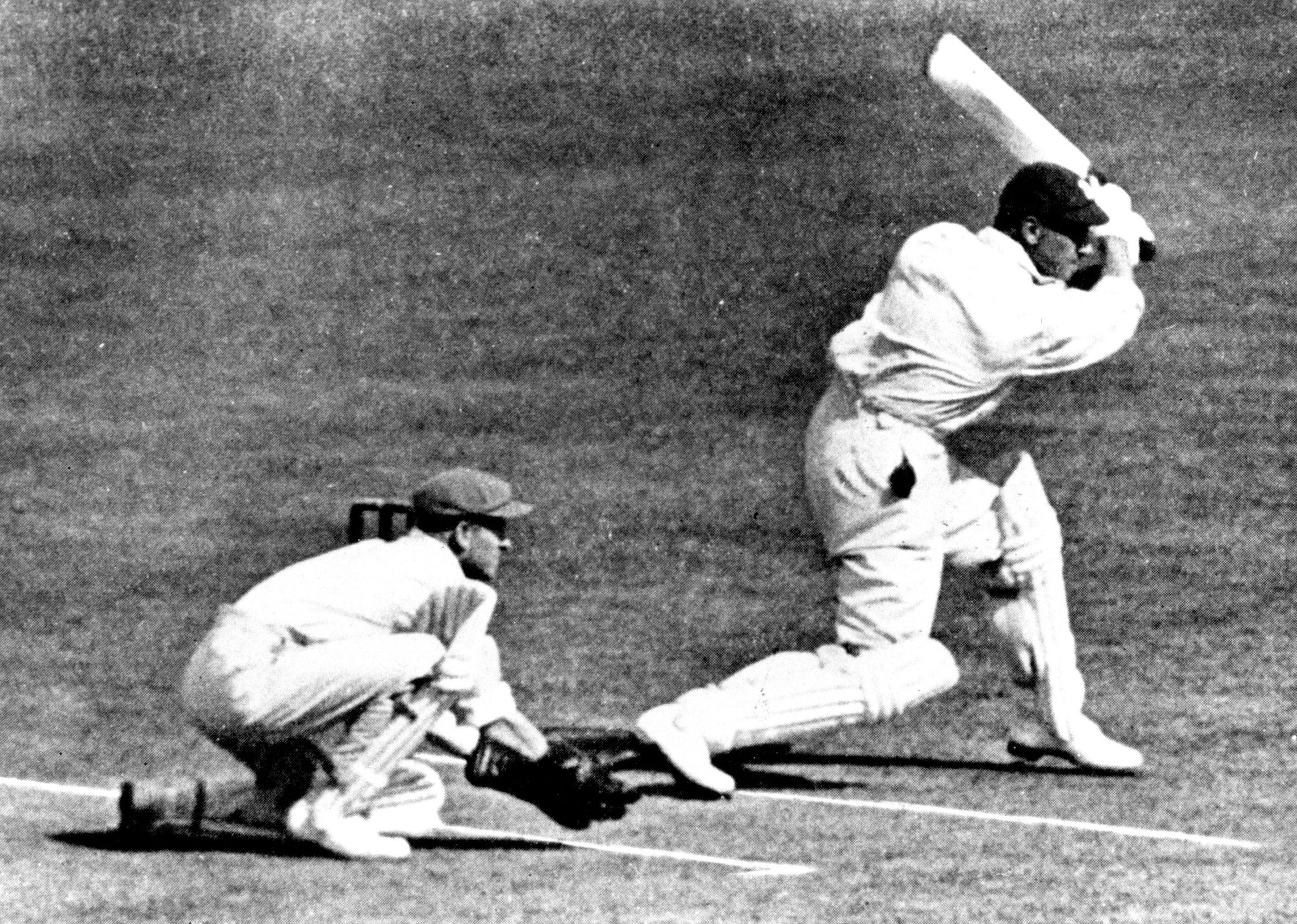

English players were so impressed that they ordered photographs of themselves from him before returning home. In 1928 he took what is regarded as one of the finest of all cricketing photographs of Wally Hammond cover driving at the Sydney Cricket Ground.

Hammond goes on the drive in one of sport’s most famous images

H H FISHWICK/FAIRFAX MEDIA

For the Bodyline tour, Fishwick was assigned to cover Jardine’s team extensively, even travelling the 2,400 miles to Perth by train to meet them off the boat from England. Throughout the tour he was credited as “the [Sydney Morning] Herald’s special photographer with the English cricketers”.

What has not been recorded until now is that he carried out his extraordinary work amid personal tragedy only days after taking one of his most enduring shots of Woodfull being hit.

Fishwick’s innovative approach prompted others to imitate his methods but he remained the leader in the field. Photographers were restricted in where they could situate themselves inside cricket grounds but he favoured angles from fine leg or third man so that he could take in the many close fielders as well as batsman and bowler. This was especially significant during the Bodyline Tests.

Woodfull clutches his chest after being hit by Larwood

H H FISHWICK/FAIRFAX MEDIA

This was the position from which he captured the image of Woodfull, probably from the top of the famous Adelaide scoreboard, which was a regular eyrie for cameramen. The incident happened on the second day of the game, a Saturday on which there were 50,962 inside the ground.

The spectators were incensed at Woodfull’s injury — there were fears that some might scale the picket fence around the field and a heavy police presence was needed to keep control — but it took time for the story to spread across Australia and reach Britain.

There was radio commentary of the matches but only 375,000 licence holders among an Australian population of 6.6million, and newsreel companies were also at the game but their coverage was rarely quickly available. Newspapers had the widest immediate audiences, with the Sydney Morning Herald being distributed to rural regions under its sister title, the Sydney Mail.

The Sydney Sun, an evening paper, published a crude photograph of the Woodfull incident on the Monday under the heading, “The Ball that Hit Woodfull”, but Fishwick’s superior shot appeared the next morning in the Herald.

Alongside it were other images from Fishwick showing England’s packed leg-side field, including one of Don Bradman — the principal target of Jardine’s strategy after he had scored a record 974 runs in the Ashes Tests in England in 1930 — being caught there by Gubby Allen off Larwood for eight.

The English cricket team before the 1928 Ashes series

H H FISHWICK/FAIRFAX MEDIA

These photographs did not appear sooner for logistical reasons. The Sydney Sun said that its shots from Adelaide were “rushed to Sydney by train, car and aeroplane”. How the Herald got its images back to the offices is unclear, but since 1929 it had possessed the capacity to wire picture-grams from Melbourne, though they took 90 minutes to send.

Fishwick’s shot of Bradman being bowled first ball by Bill Bowes during the second Test in Melbourne was sent by picture-gram in time to appear in the next morning’s paper. Whether the same thing could be done from Adelaide is uncertain.

Today’s sports photographers can take about 30 images a second but Fishwick was far more restricted. Even so, he was marking new territory at this time. His was described as “the most powerful telephoto lens ever produced” while he used “special Kodak super-sensitised panchromatic film, enabling fully exposed negatives to be obtained at a speed of 1/1,000th of a second”.

The mood against Bodyline took a decisive shift in the days after Woodfull was hit on the Saturday and Oldfield on the Monday — an image of the Oldfield incident appeared on the front page of the Melbourne Herald less than 24 hours later — by which time other factors were at play.

Someone in the Australian dressing room leaked an account of what Woodfull had said to Pelham Warner, the England manager, after Warner had paid a visit to ask about Woodfull’s wellbeing. Woodfull famously replied: “I don’t want to see you, Mr Warner. There are two teams out there. One is trying to play cricket and the other is not.” Woodfull had previously kept his views on Bodyline private. Now they were out in the open. The source of the leak was unknown but it is now widely accepted that it was Bradman.

Fishwick, left, the English immigrant based in Sydney whose work is considered groundbreaking

FAIRFAX MEDIA

Two days after the leak was reported, and a day after Fishwick’s photographs appeared, the Australian Cricket Board voted 8-5 to send a cable of protest to MCC in London. This triggered a series of exchanges that almost led to the cancellation of the tour and ultimately resulted in MCC, the ruling body of English cricket, scapegoating Jardine and Larwood to ensure Australia toured England in 1934.

As only four of the 13 delegates attended the Adelaide Test, it is reasonable to assume that their views were at least partly shaped by the media coverage.

While the diplomatic exchanges between the two countries unfolded, Fishwick made use of the three-week gap before the fourth Test in Brisbane to take a short holiday with his 17-year-old daughter, Muriel.

Three days after the conclusion of the Adelaide Test, the car Fishwick was driving from Batemans Bay to Wollongong, south of Sydney, overturned on a sharp bend on the Gerringong Road. Muriel was thrown from the vehicle and her skull crushed by the car’s bonnet. Herbert was helped out from under the car by a passer-by, and remarkably was unhurt.

At a coroner’s inquiry two weeks later Fishwick appeared to blame himself for his daughter’s death, saying he had misjudged the curve, but the coroner ruled that the corner where the incident occurred was dangerous and gave a verdict of accidental death. The incident made news across the country.

A week later Fishwick was back working at the Brisbane Test, his camera capturing Woodfull being hit again by Larwood’s bowling, though less seriously. England won the match to go 3-1 up and regain the Ashes.

Such was the originality of Fishwick’s work that just over two weeks after the England team returned from Australia, a display of his pictures was put on at Shell-Mex House in London. The Daily Express called it “a remarkably fine exhibition of high-speed action photographs”. Several reviews of the photographs said they showed Bradman and Bill Ponsford ducking to balls “only waist high” — in other words, that Australia had been overstating the dangers.

The display was opened by Warner, whose speech was his first public utterance on Bodyline since coming home. He pleaded for peace between England and Australia, saying: “I hope that everyone will refrain from any comment which will in any way add fuel to the flames.”

The Sydney Mail closed in 1938 and Fishwick went freelance but he never stopped advancing his art, pioneering a camera designed to allow colour printing. He became an expert in animal photography. He died in 1957 but his contribution to cricket’s greatest episode was largely forgotten in England. He was not given an obituary by Wisden until almost 60 years after his death.

Mike Bowers, who wrote A Century of Pictures, Celebrating 100 Years of Herald Photography, said: “Fishwick revolutionised the way cricket was photographed and rewrote the rules on all sports photography. I believe the birth of long-lens photography can be traced to the Sydney Morning Herald. I’m sure his photographs influenced public opinion on Bodyline.”