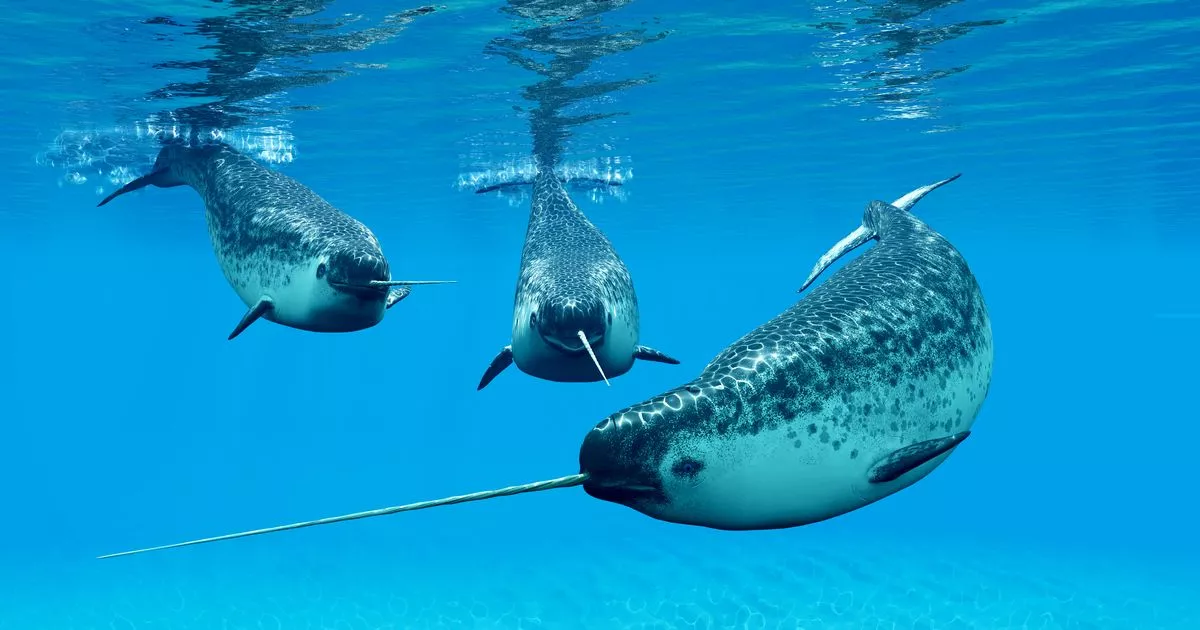

The species of whale is commonly referred to as the ‘unicorn of the sea’ Narwhal whales live in social groups called pods and inhabit the Arctic Ocean; males have distinctive tusks.(Image: Getty Images)

Narwhal whales live in social groups called pods and inhabit the Arctic Ocean; males have distinctive tusks.(Image: Getty Images)

A team of specialists in Cork examined the remains of a species of whale that has never been seen before in Ireland and confirmed that it was a rare narwhal, typically native to the Arctic.

The small whale carcass washed up in Donegal last weekend and was reported to the Irish Whale and Dolphin Group, who then transported it down to the Regional Veterinary Lab in Cork, where it was examined by a group of marine mammal ecologists and pathologists.

They soon confirmed it as a narwhal, making it the first on record to appear in Ireland. It was a young female, measuring 2.42m in length and in quite poor condition.

The Narwhal, sometimes referred to as the ‘unicorn of the sea’, is a toothed whale found exclusively in the Arctic waters of the North Atlantic, north of 60°. They are rarely recorded outside the Arctic, with the last stranding record in western Europe a young male washed up dead in Belgium in 2016. Prior to that record, two females were stranded in the Thames Estuary, England, in Kent in 1949.

The only sightings are of two off Orkney and one off Aberdeenshire in Scotland in 1882, and one in the Hebrides in 1976. This is only the 10th recorded stranding of a narwhal in western Europe, and it is the fourth female recorded. As a young female, there was no tusk – only males, and occasionally females, have one.

There are an estimated 170,000 living narwhals worldwide. The population is threatened by the effects of climate change, such as a reduction in ice cover and human activities, such as pollution and hunting. Narwhals have been hunted for thousands of years by Inuit in northern Canada and Greenland for meat and ivory, and regulated subsistence hunting continues to this day.

The skeleton has been kept by the IWDG to prepare the skeleton for the National Museum of Ireland (Natural History).

Speaking about the discovery, Minister for Nature, Heritage and Biodiversity Christopher O’Sullivan TD said: “I’d like to thank everyone who was involved in retrieving the stranded Narwhal for their rapid response and collaboration, from the young people who initially spotted it on the beach and raised the alert, to the dedicated teams in the Irish Whale and Dolphin Group, the Regional Veterinary Laboratory in Cork and the National Parks and Wildlife Service of my own Department.

“This is a significant event and it is important that we try to find out more about why this species arrived on our coastline. An examination is underway which I hope will reveal important details about its life and history, and shed some light on the reasons why it arrived on our shores. The Narwhal is an arctic species that is mainly found in cooler waters. Findings like this are a stark reminder of the vulnerability of wildlife in the face of a changing climate, and the need to protect them.”

Earlier this year, a huge whale carcass, measuring over 17m long, washed up on Barleycove Beach in West Cork. Fin whales are common around Ireland’s southern coasts and can be over 25 metres long, according to the National Biodiversity Data Centre.