About 9,000 years ago, part of Antarctica’s eastern ice sheet collapsed astonishingly fast, driven by warmer ocean water. The study focuses on the East Antarctic Ice Sheet, a vast body of land ice in East Antarctica.

Altogether, Antarctica’s ice holds enough water to raise sea levels by about 190 feet if it melted. Fresh evidence from seafloor sediments near Japan’s Syowa Station now links that ancient collapse to warm deep ocean currents.

The work was led by Prof. Yusuke Suganuma at the National Institute of Polar Research (NiPR) in Tokyo, Japan. His research focuses on how Antarctic ice sheets responded to past climate warming, to better understand future sea level changes.

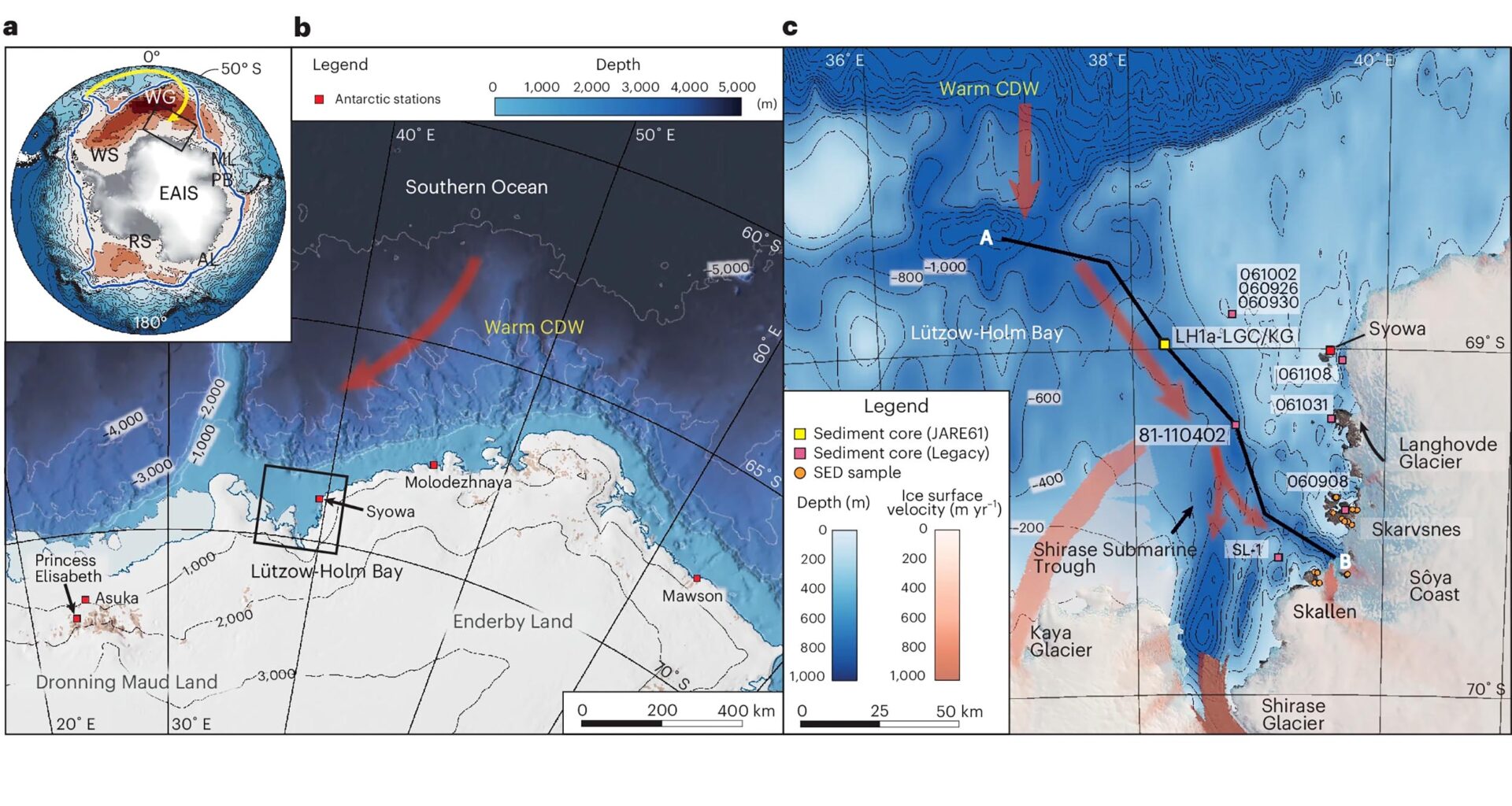

In a recent study, the team traced the collapse using sediment cores taken from Lutzow-Holm Bay’s seafloor.

Layers of mud captured changes during the early Holocene, a warm stretch after the last ice age, when temperatures exceeded today’s.

By measuring rare beryllium isotopes and tiny marine fossils, the group pinned the timing of ice-shelf breakup to around 9,000 years ago.

The key player is circumpolar deep water, a relatively warm salty current circling Antarctica, which flows hundreds of feet below the surface.

Around 9,000 years ago, that deep water surged onto the continental shelf, undercutting floating ice shelves and stripping away their structural support.

Once those shelves fractured, they no longer braced the ice sheet behind them, so inland ice flowed faster toward the ocean.

Climate and ocean models indicate that warm deep water lingered in the bay before collapse, showing a strong, repeated pulse of ocean heat.

Feedback loop feeds on meltwater

The team found that the ice and ocean formed a positive feedback loop. Meltwater from Antarctic regions freshened the surface ocean, allowing warm deep water to move landward in what researchers call a “cascading positive feedback”.

That extra fresh water increased stratification, the layering of lighter water above heavier water, which stopped cooler surface water from mixing downward.

As more ice melted, more fresh water spread around Antarctica, locking in warm deep water and accelerating the loss of floating shelves.

Speed of previous Antarctica collapse

Several factors came together in Dronning Maud Land to make the collapse rapid, including rising sea level and the shape of the seafloor.

As the ice sheet lost mass, glacial isostatic adjustment, a slow rebound of Earth’s crust, briefly raised sea level along this coast.

The bay contains a deep submarine trough, a long narrow underwater valley, that guides warm deep water straight toward the ice front.

Higher local sea level let the ice float easily, so warm deep water penetrated farther beneath the shelves and ungrounded inland ice.

Map for sediment core locations and oceanographic features in LHB, East Antarctica, comparable to collapse 9,000 years ago. Credit: Nature Geoscience. Click image to enlarge.West Antarctic glaciers

Map for sediment core locations and oceanographic features in LHB, East Antarctica, comparable to collapse 9,000 years ago. Credit: Nature Geoscience. Click image to enlarge.West Antarctic glaciers

In West Antarctica, observations show that Thwaites Glacier is thinning as warm seawater intrudes beneath the grounded ice.

Measurements near Thwaites’s ice shelf show a thickening layer of modified deep water at the seabed.

These modern observations echo the Holocene pattern, with warm deep water thinning shelves from below and encouraging the grounded ice upstream to retreat.

Other West Antarctic outlets, including Pine Island Glacier, also show rapid retreat where deep water can reach their undercut grounding zones.

East Antarctica stability

For years, many scientists viewed East Antarctica as relatively stable because much of its ice sits on bedrock above sea level.

The new reconstructions show that even sectors grounded largely on rock can thin quickly if warm water finds hidden pathways beneath the ice.

Recent satellite and gravity measurements reveal ongoing ice loss from East Antarctic coastal sectors, including vulnerable outlets like Totten and Denman.

The Holocene collapse in Dronning Maud Land shows that once the ocean warms and freshens enough, a stable region can begin rapid retreat.

Troubling Antarctic climate system

Around Antarctica, the Antarctic Circumpolar Current, a strong ring of water flowing west to east, transports heat and freshwater around the Southern Ocean.

The Holocene simulations suggest that meltwater entering this circulation changed water density in the Southern Ocean, steering warm deep water toward East Antarctica.

Modern climate models find that freshening from Antarctic melt can reduce mixing in the Southern Ocean, sending heat closer to the ice edge.

When that happens, the line between a slow, manageable loss of ice and a runaway retreat can become dangerously thin.

Antarctic collapse and sea levels

If East Antarctica began to collapse, losing ice at Holocene-like rates, global sea levels would rise much faster than current projections assume.

No one expects the ice sheet to vanish overnight, yet even a few feet of sea level this century would redraw many coastlines.

The new results underline that future Antarctic ice loss depends strongly on how much heat the ocean absorbs from human greenhouse gas emissions.

Ice sheet models that omit these meltwater feedbacks may underestimate how fast shelves can break apart and release inland ice into the ocean.

Rapid sea level rise would bring higher storm surges, more frequent nuisance flooding, and saltwater intrusion to coastal cities and low-lying islands worldwide.

Because ice sheets change slowly compared with human lifetimes, decisions over the next few decades will shape sea level for many generations.

The story recorded in those Antarctic sediments shows that once warm water and meltwater collaborate, ice systems can respond in surprisingly abrupt ways.

By piecing together what happened 9,000 years ago, researchers are narrowing the range of futures we face as greenhouse gas levels rise.

The study is published in Nature.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–