Every so often, astronomers will witness an incredible and mysterious phenomenon – startlingly bright, electric blue flashes in the night sky that blaze for days and then fade away, leaving behind a whisper of X-rays and radio waves.

With barely more than a dozen on record, these events, which are known as luminous fast blue optical transients (LFBOTs), have defied easy categorization.

Were they weird supernovae? Gas slurped by a lurking black hole? The brightest burst yet, spotted in 2024 and cataloged as AT 2024wpp, finally tipped the scales.

Source of the bright flashes

A team of experts at UC Berkeley now argues that these flashes are the calling card of an extreme tidal disruption: a hefty black hole, up to about 100 times the mass of the Sun, tearing its massive stellar companion to pieces in a matter of days.

“The main message from AT 2024wpp is that the model that we started off with is wrong,” said lead optical analyst Natalie LeBaron. “It’s definitely not caused by an exploding star.”

Astronomers first met this class in 2018 with AT 2018cow – the “Cow” – whose cheeky nickname sparked a barnyard of successors (the Koala, the Tasmanian Devil, the Finch).

LFBOTs rise fast, glow a striking blue in optical light, pour out ultraviolet and X-rays, and then fade on timescales of days to weeks. AT 2024wpp, nicknamed the Woodpecker, outshone them all.

It was five to ten times more luminous than the Cow and sitting on the outskirts of a star-forming galaxy about 1.1 billion light-years away.

LFBOTs vs. supernovae

The Berkeley team analyzed AT 2024wpp through two separate studies. One, led by postdoc A.J. Nayana, traced its X-ray and radio emissions. The other, led by LeBaron, focused on mapping the optical, ultraviolet, and near-infrared light.

When the researchers tallied the radiated energy, the numbers ruled out a supernova hypothesis. The outburst emitted roughly 100 times what a normal stellar explosion could plausibly produce in such a short window.

This output is equivalent to converting an unthinkable fraction of a Sun’s rest mass into light in mere weeks. No traditional core-collapse event could power such a burst.

“The sheer amount of radiated energy from these bursts is so large that you can’t power them with the collapse and explosion of a massive star – or any other type of normal stellar explosion,” LeBaron explained.

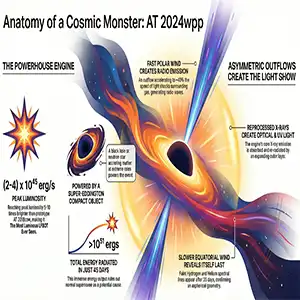

Anatomy of a stellar shredding

If not a supernova, then what? The data point to a black hole-star binary with a long and complex history.

Over time, the black hole siphoned material from its companion, building a bloated shroud of gas around itself. The gas was too distant to be swallowed outright and dense enough to shape what followed.

At last, the companion wandered too close. Gravity did the rest. The star was stretched and torn, then flung into a whirling accretion disk.

Fresh debris plowed into the older envelope, creating violent shocks that blazed across the spectrum in X-rays, ultraviolet, and that signature blue light.

Some of the newly liberated gas funneled toward the black hole’s poles, where magnetic fields launched twin jets.

Blasting outward at roughly 40 percent of the speed of light, the jets slammed into surrounding material and lit up the radio sky – a clear sign for outflows powered by accretion.

LFBOTs are truly cosmic monsters, powered by the shredding of a massive star by a black hole the mass of 100 suns. An LFBOT discovered last year, AT 2024wpp, provided the data astronomers needed to narrow down the origins of these bursts. Credit: Raffaella Margutti/UC Berkeley. Click image to enlarge.Wolf-Rayet stars

LFBOTs are truly cosmic monsters, powered by the shredding of a massive star by a black hole the mass of 100 suns. An LFBOT discovered last year, AT 2024wpp, provided the data astronomers needed to narrow down the origins of these bursts. Credit: Raffaella Margutti/UC Berkeley. Click image to enlarge.Wolf-Rayet stars

The team’s modeling suggests a black hole in the elusive “intermediate-mass” regime – tens to one hundred solar masses – paired with a big, hot star at least ten times the mass of the Sun.

One leading candidate is a Wolf-Rayet star, an evolved giant stripped of much of its hydrogen.

That would neatly explain the weak hydrogen emission seen from AT 2024wpp while matching the star-forming neighborhood where such massive stars are common.

Tracing an extreme black hole

These black holes are catnip for astronomers. While mergers of black holes heavier than 100 Suns have appeared in gravitational wave detectors like LIGO, observing such objects outside of mergers has been rare.

“Theorists have come up with many ways to explain how we get these large black holes, to explain what LIGO sees,” said UC Berkeley’s Raffaella Margutti, senior author of both studies.

“LFBOTs allow you to get at this question from a completely different angle. They also allow us to characterize the precise location where these things are inside their host galaxy, which adds more context in trying to understand how we end up with this setup – a very large black hole and a companion.”

By stitching together observations from telescopes around the world, the team reconstructed the sequence of events.

It began with a brilliant flash as debris slammed into preexisting gas, followed by a slower ultraviolet and optical cool-down.

A pulsing X-ray signal then emerged from near the black hole, and a final radio surge marked jets energizing the surrounding material.

What LFBOTs are really telling us

LFBOTs like 2024wpp appear to be less a single phenomenon than a new window into extreme binaries.

They demonstrate how diverse – and how dramatic – stellar deaths and near-deaths can be when a black hole is nearby.

These events also offer a testbed for accretion physics under extraordinary conditions, where infalling matter collides with older outflows and where jets ignite almost immediately after a star is torn apart.

Because LFBOTs erupt in the outskirts of star-forming galaxies, they carry clues about where and how hefty black holes pair up with massive companions in the first place.

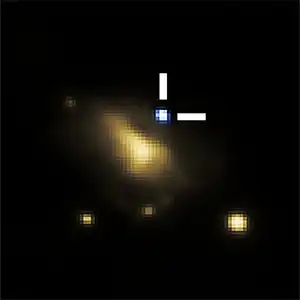

AT 2024wpp, a luminous fast blue optical transient, or LFBOT, is the bright blue spot at the upper right edge of its host galaxy, which is 1.1 billion light-years from Earth. Credit: Aidan Martas/UC Berkeley. Click image to enlarge.New ways to find LFBOTs

AT 2024wpp, a luminous fast blue optical transient, or LFBOT, is the bright blue spot at the upper right edge of its host galaxy, which is 1.1 billion light-years from Earth. Credit: Aidan Martas/UC Berkeley. Click image to enlarge.New ways to find LFBOTs

Right now, the pipeline delivers about one LFBOT a year, which is hardly enough for a census. That’s poised to change.

These events are UV powerhouses, so dedicated ultraviolet observatories will be game-changers.

Two missions – ULTRASAT and UVEX, the latter with strong ties to Berkeley’s Space Sciences Laboratory – are slated to bring sensitive, wide-field UV eyes to the problem in the coming years.

Catching LFBOTs early, before they peak, will let astronomers dissect their rise, map their environments, and see how varied the progenitor systems really are.

“Once we have UV telescopes in place in space, then finding LFBOTs will become routine, like detecting gamma-ray bursts today,” said Nayana.

Routine doesn’t have to mean dull. Each new flash serves as a fresh laboratory for studying gravity, radiation, and raw celestial chaos.

It’s another opportunity to watch a black hole in action and to uncover how the universe forges the monsters that LIGO detects colliding in the cosmic dark.

Preprints of the two articles can be found on arXiv.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–