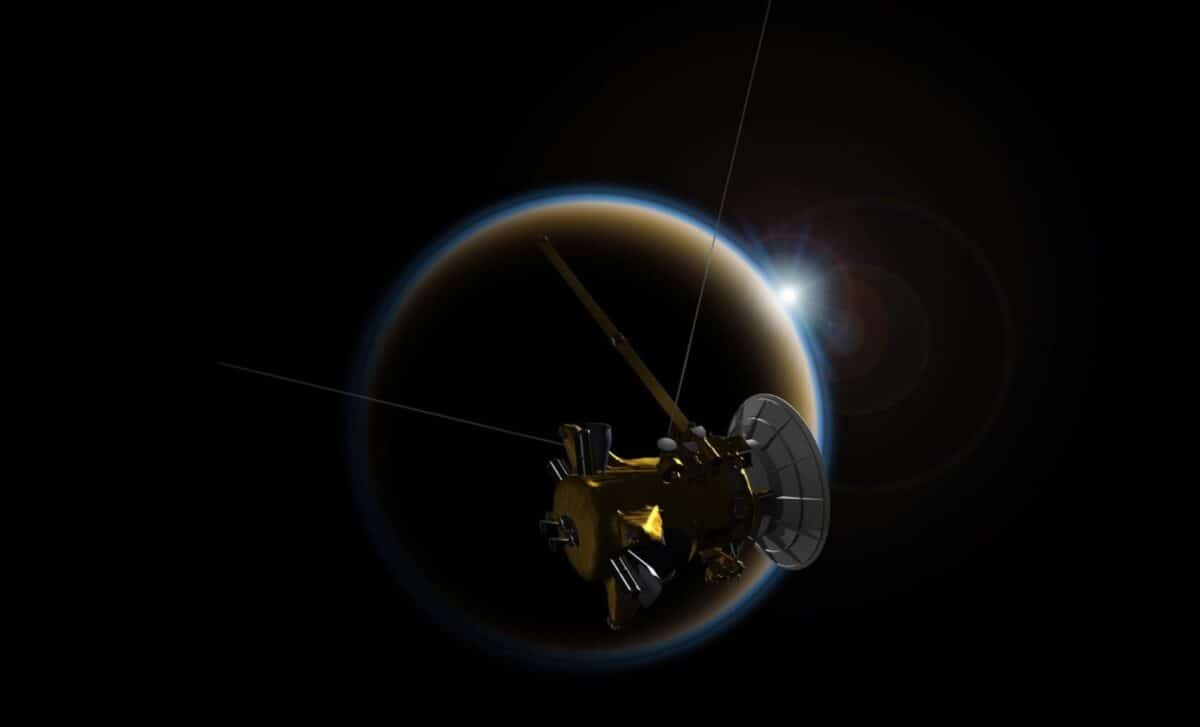

Saturn’s moon Titan may no longer be the ocean world scientists once believed it was. A new analysis of data from NASA’s Cassini mission points to a slushy interior instead of a global subsurface ocean.

Re-examining gravity and tidal flexing data from the Cassini spacecraft, researchers have proposed a different structure beneath Titan’s icy crust: not a vast sea of water, but a semi-solid mix of ice and slush. While this finding alters Titan’s place in the rankings of potentially habitable moons, it doesn’t rule out localized pockets of liquid water beneath the surface.

Titan’s Hidden Ocean May Never Have Existed

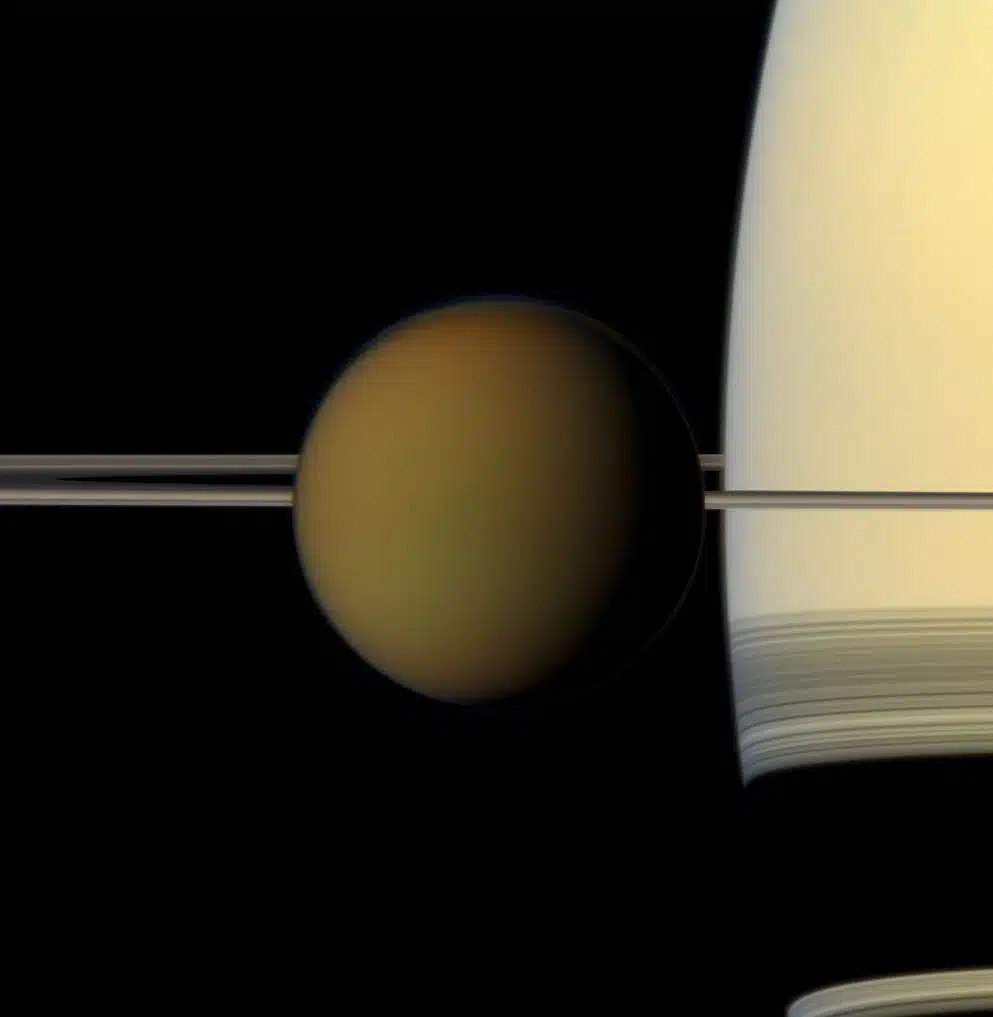

Titan has long been a key target in the search for extraterrestrial habitability due to its dense atmosphere, surface lakes of methane, and, until now, the belief that it harbored a deep liquid ocean beneath its outer shell.

The original conclusion, drawn in 2008, was based on how Saturn’s gravity caused Titan to stretch and flex, a behavior interpreted as evidence for a liquid layer inside. These tidal distortions affected the spacecraft’s velocity in measurable ways, which scientists tracked using radio signals. In a press release from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, senior research scientist Julie Castillo-Rogez stated:

“It is important to remember that the data these amazing spacecraft collect lives on so discoveries can be made years, or even decades, later as analysis techniques get more sophisticated,” he added “It’s the gift that keeps giving.”

🚨: This is NOT a blurred photo of Earth.

It’s Saturn’s largest moon Titan and the only other known world with liquid on its surface.

Captured by James Webb Telescope 🤩 pic.twitter.com/gHjFM3Kcsu

— All day Astronomy (@forallcurious) November 2, 2025

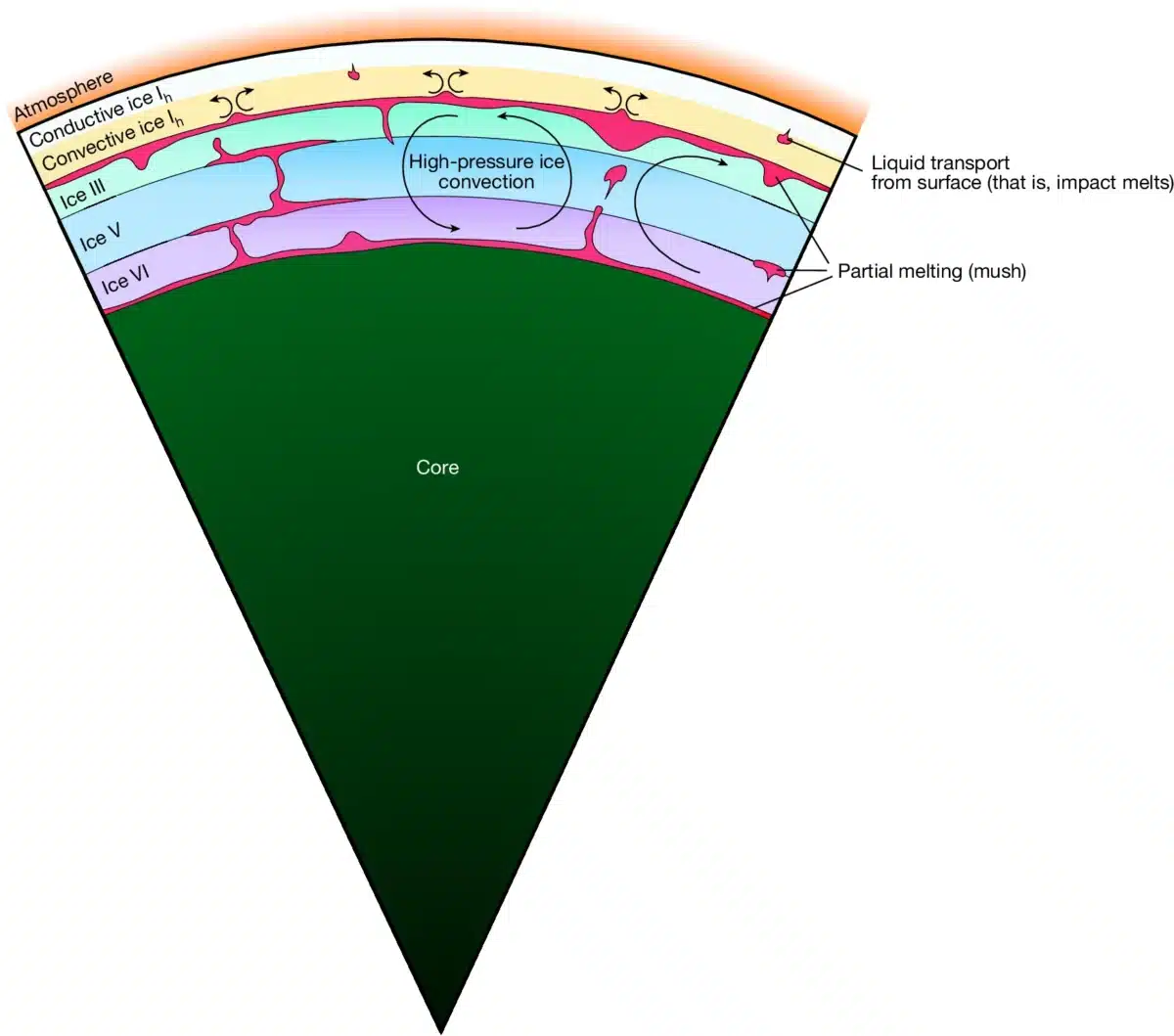

A Slushy Core Replaces The Ocean Hypothesis

The re-analysis, published on December 17, 2025, in Nature, introduced a new model of Titan’s interior that replaces the earlier ocean theory with a thick, partially frozen mixture of ice and water. Using a technique to better filter out noise from the Doppler data gathered by Cassini, researchers found stronger-than-expected energy dissipation, inconsistent with a global liquid ocean.

This higher energy loss supports a structure where the moon’s interior is flexible enough to deform under Saturn’s gravitational pull, but not fluid enough to sustain a true ocean. The earlier theory had assumed that tidal forces created enough heat to maintain a full ocean of liquid water beneath the crust. But the new interpretation shows that the heat may be absorbed and dispersed by the slushy layers before a true melt occurs.

This slushy composition would still allow for tidal flexing, the very phenomenon used to propose the ocean in the first place, but with a different thermal outcome. The moon’s shell behaves in a way that mimics a liquid-bearing world, though the actual state of the interior is more complex and significantly less oceanic than previously believed.

Titan’s deep interior exposed in new analysis. Credit: Nature

Titan’s deep interior exposed in new analysis. Credit: Nature

Pockets Of Warmth May Still Exist Below

While a global subsurface ocean may no longer be on the table, Titan isn’t completely frozen solid. According to Flavio Petricca, a postdoctoral researcher at JPL and lead author of the study, Titan likely contains pockets of liquid water trapped near its rocky core.

“Our analysis shows there should be pockets of liquid water […] cycling nutrients from the moon’s rocky core through slushy layers of high-pressure ice to a solid icy shell at the surface,” he noted.

This finding is especially significant because these localized environments could still host the basic conditions for life, or at least prebiotic chemistry. Unlike a uniform ocean, isolated reservoirs of liquid water offer different scenarios for how chemical compounds might interact over time. It doesn’t eliminate Titan from the conversation on habitability, it just changes the terms.

Titan drifts past Saturn in this striking image from NASA’s Cassini mission. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

Titan drifts past Saturn in this striking image from NASA’s Cassini mission. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

Cassini Data Continues To Deliver After Two Decades

The reassessment underscores the enduring scientific value of legacy mission data. Though Cassini ended its mission in 2017, the data it transmitted continues to challenge and update planetary models.

“This research underscores the power of archival planetary science data,” said Castillo-Rogez of JPL.

Researchers used sharper techniques to analyze Doppler shift data, those tiny frequency changes in the spacecraft’s radio signals that hint at how Titan’s gravity behaves. By cleaning up the noise in the old signals, they were able to map out the moon’s interior more clearly than ever before.