Light already carries our phone calls, videos, and emails across the world through optical fibers, but the same light has a deeper, quantum side that could revolutionize how we communicate.

If we can send information using single particles of light, called photons, we could build communication systems that are almost impossible to hack. The challenge has been finding a reliable way to generate these single photons under real-world conditions.

Now, researchers in Japan have demonstrated a way to achieve this. They can make a carbon nanotube emit exactly one photon from a single, precisely chosen spot, even at room temperature and at wavelengths used in today’s telecom networks.

The problem of unpredictable light

For quantum communication to work, light sources must emit photons one at a time, not in random bunches. Several materials can do this, but most require extreme conditions like very low temperatures.

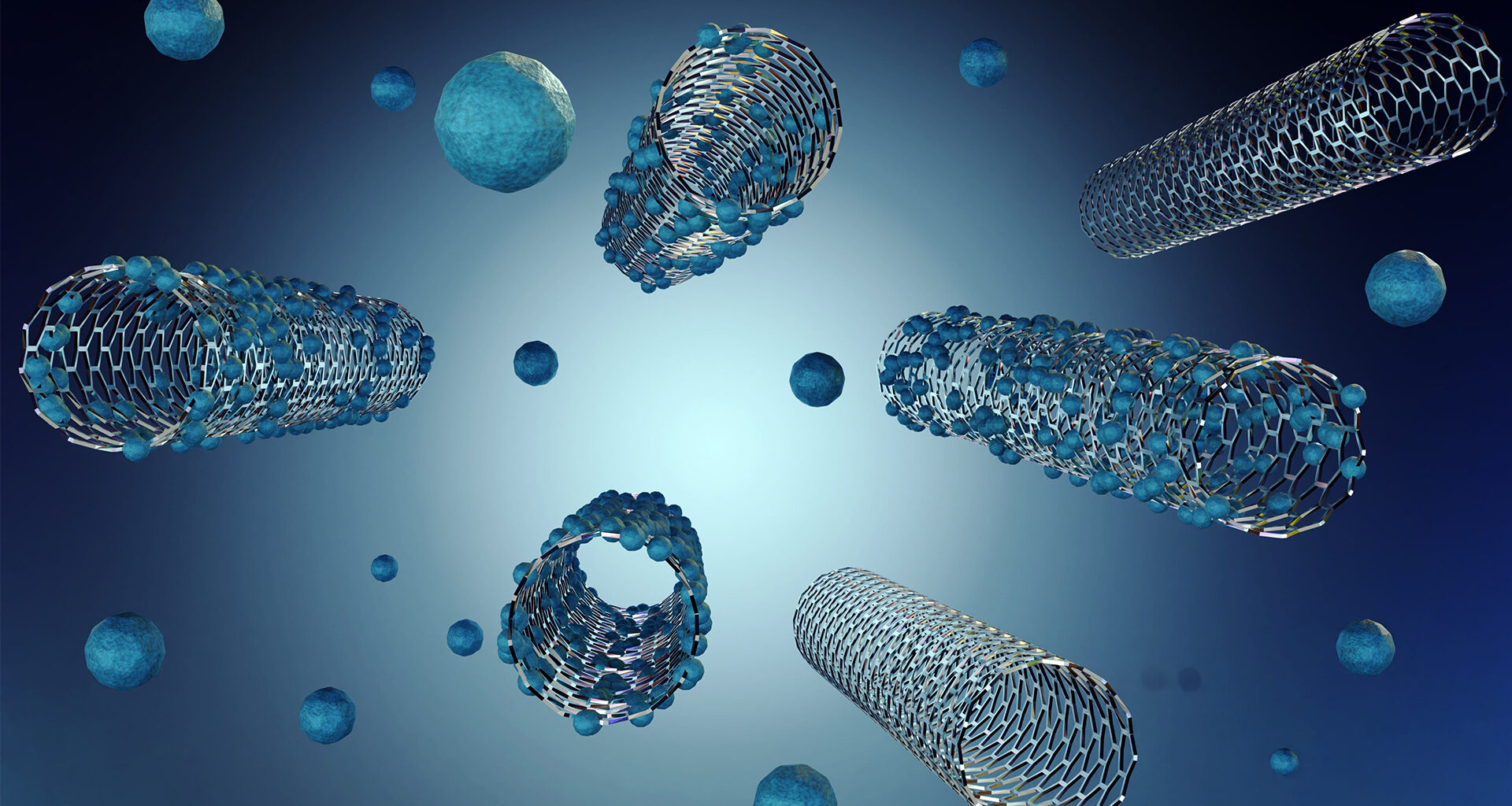

Carbon nanotubes (tiny cylinders made of carbon atoms) stand out because they can emit single photons at practical temperatures and wavelengths. This makes them highly attractive for practical devices.

However, they have had a stubborn problem. Along their length, multiple spots can emit light, and scientists had little control over how many such spots formed or where they appeared.

Without precise control, the emitted light becomes unpredictable, which is unacceptable for quantum technologies. Until now, no method could reliably create just one light-emitting site at a known location on a nanotube.

Making carbon nanotubes emit a single photon

Kato and his team solved this by combining careful fabrication with real-time monitoring. First, they suspended a single carbon nanotube across a trench only a few micrometers wide.

This setup isolated the nanotube and made it easier to control what happened along its length. They then exposed the nanotube to a vapor of iodobenzene, a chemical that can react with carbon under the right conditions.

Next came the key step. The researchers focused an ultraviolet laser beam onto one specific point on the nanotube. The ultraviolet light triggered a reaction between the nanotube and the iodobenzene molecules, creating a tiny defect in the carbon structure.

This defect, known as a color center, is a precisely engineered quantum defect that traps excitons, bound pairs of electrons and holes, and releases their energy as light in the form of single photons. In other words, it acts as the nanotube’s quantum light source.

To make sure only one color center formed, the team continuously monitored the light coming from the nanotube. As soon as they detected a change in the light that signaled the creation of a color center, they immediately stopped the reaction.

“By monitoring discrete intensity changes in photoluminescence spectra, we achieve precise control over the formation of individual color centers,” the study authors note. This careful timing prevented additional defects from forming.

Moreover, by moving the laser beam, they could choose where the color center appeared, controlling its position to within about a micrometer. “This level of control paves the way for the development of atomically defined technology for scalable quantum photonic circuits, operating at room temperature within the telecom band,” the study authors added.

Next comes the chip

This advancement would allow the direct integration of carbon nanotubes into existing optical fiber networks. In the long term, such devices could enable ultra-secure communication systems where any attempt to intercept the signal would be immediately detectable.

However, scaling up the process so that many identical single-photon emitters can be manufactured reliably will take more time and effort. Integrating these nanotubes into complex photonic circuits on chips is another hurdle.

However, the researchers are already looking forward. Their next goal is to build chip-based devices.

“We want to integrate them into photonic circuits on chips, and then once we have a chip, we can probably start talking to photonics manufacturers about real-world applications,” Kato said.

The study is published in the journal Nano Letters.