The question of whether environmental factors can alter traits in future generations through epigenetic changes rather than DNA sequence mutations has long been controversial in genetics. Observations of disease and metabolic changes in offspring following parental exposure to stress, toxins, or poor nutrition have suggested such inheritance might occur, but proving causality has remained elusive.

“The germline-specific epigenome editing system developed in this study enabled us to validate the inter/transgenerational inheritance theory directly”Takuro Horii et al.

The challenge lies in distinguishing whether observed changes result from true transmission of altered epigenetic marks, or whether those marks are first erased after fertilisation and then independently re-established during development. To address this directly, Takuro Horii and colleagues at Gunma University developed a germline-specific epigenome-editing system that enables targeted modification of DNA methylation patterns in developing sperm without altering the underlying genetic sequence.

»Epigenome editing using a ‘dead’ Cas9 (dCas9), which does not introduce genetic changes and can rewrite the epigenetic information at a target locus, may be a direct method that can help solve this problem,« the authors note in a paper that was published Nature Communications on Christmas Day.

The research team engineered mice to express epigenome editing machinery exclusively during spermatogenesis. To this end, they used a catalytically inactive Cas9-SunTag system, driven by the spermatogenesis-specific Stra8 promoter, to recruit the TET1 demethylase catalytic domain to target loci during sperm development.

This system was designed to remove DNA methylation at the H19 differentially methylated region (H19-DMR), a genomic imprinting control element in which methylation status determines parent-of-origin-specific gene expression. In healthy individuals, the paternally inherited H19-DMR is heavily methylated whilst the maternal allele remains unmethylated, a pattern that regulates expression of the growth-promoting Igf2 gene. Loss of paternal methylation at this locus in humans causes Silver-Russell syndrome, characterised by severe intrauterine growth restriction.

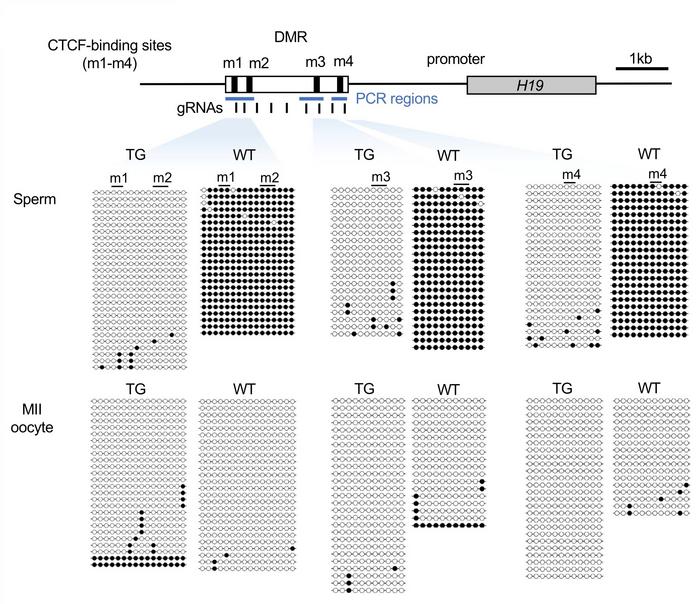

Figure 1. Complete erasure of DNA methylation at H19-DMR in edited sperm. Adopted from Figure 2d in Horii et al. (2025) Nature Communications, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Figure 1. Complete erasure of DNA methylation at H19-DMR in edited sperm. Adopted from Figure 2d in Horii et al. (2025) Nature Communications, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Bisulfite sequencing confirmed complete erasure of DNA methylation across the H19-DMR in sperm from transgenic males, with minimal off-target effects (see Figure 1). When these males were crossed with wild-type females, offspring exhibited reduced birth weight, altered Igf2 and H19 expression levels, postnatal growth retardation, and body asymmetry.

Critically, offspring that did not inherit the transgene construct still displayed these phenotypes, confirming that the effects resulted from inherited loss of methylation rather than continued expression of editing factors.

»The germline-specific epigenome editing system developed in this study enabled us to validate the inter/transgenerational inheritance theory directly, because it involves editing of the germline epigenome alone and not the genome,« the authors conclude. »Induced loss of DNA methylation at the DMR in sperm was partially transmitted to the F1 offspring, which exhibited resulting phenotypes.«

However, detailed methylation analysis revealed an unexpected finding. Whilst sperm carried completely demethylated H19-DMR, newborn offspring showed partial restoration of methylation, particularly at the 5′ end of the regulatory region. Time-course experiments demonstrated that this recovery began during preimplantation development, with substantial remethylation occurring by the morula stage. The discovery of this ‘intergenerational DNA methylation recovery’ suggested the existence of epigenetic memory that instructs the placement of new methyl groups at specific genomic locations despite loss of the original methylation mark.

“H3K9me3, which is deposited shortly after fertilization, is required for the subsequent de novo DNA methylation at the H19-DMR”Takuro Horii et al.

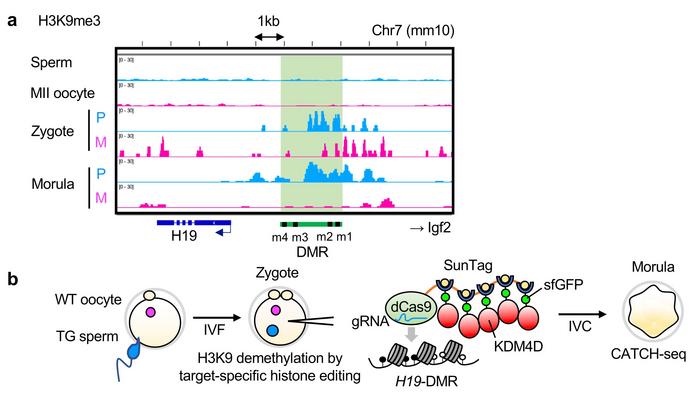

To identify the molecular basis of this memory, the researchers examined histone modifications using an ultra-sensitive chromatin profiling technique called CATCH-seq. They discovered that tri-methylation of histone H3 at lysine 9 (H3K9me3) appears at the paternal H19-DMR around five hours post-fertilisation, precisely when DNA methylation is absent (see Figure 2). This mark accumulates during early cell divisions, and its distribution corresponds to regions where DNA methylation subsequently recovers most robustly.

Figure 2. Target-specific removal of H3K9me3 around H19-DMR. a) H3K9me3 appears at paternal H19-DMR after fertilisation and accumulates through the morula stage. b) CRISPR-based histone editing with KDM4D eliminates this mark. Adopted from Figure 5ab in Horii et al. (2025) Nature Communications, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Figure 2. Target-specific removal of H3K9me3 around H19-DMR. a) H3K9me3 appears at paternal H19-DMR after fertilisation and accumulates through the morula stage. b) CRISPR-based histone editing with KDM4D eliminates this mark. Adopted from Figure 5ab in Horii et al. (2025) Nature Communications, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

The critical test came from removing H3K9me3 during early embryonic development. The team injected zygotes with RNA encoding KDM4D, an enzyme that removes H3K9me3 marks, targeted to the H19-DMR using a CRISPR-Cas-based histone editing system. Embryos lacking H3K9me3 at H19-DMR failed to restore DNA methylation during development and showed more severe growth retardation than controls. Control experiments using a catalytically inactive enzyme or targeting different histone marks did not prevent methylation recovery, demonstrating specificity. The authors conclude that »H3K9me3, which is deposited shortly after fertilization, is required for the subsequent de novo DNA methylation at the H19-DMR.«

The findings reveal a two-component epigenetic memory system at imprinted loci. DNA methylation and H3K9me3 normally co-exist at the paternal H19-DMR, providing robust genomic imprinting throughout development. When methylation is artificially removed in sperm, H3K9me3 deposited after fertilisation guides partial restoration of the missing methylation pattern. However, this recovery is not perfectly faithful, and the extent varies between individuals, correlating with offspring birth weight.

Analysis of subsequent generations demonstrated that whilst the methylation defect was partially transmitted from F0 sperm to F1 offspring, it did not persist transgenerationally. Sperm from F1 males showed restored methylation at H19-DMR, and their F2 offspring exhibited normal methylation and growth. The work thus provides experimental evidence for partial intergenerational inheritance but no transgenerational inheritance at this model locus.

The germline epigenome editing approach offers advantages over previous methods by modifying only epigenetic information whilst leaving the DNA sequence intact. Questions remain about what initially recruits H3K9me3 to the paternal H19-DMR after fertilisation, since the modification is absent in sperm.

The researchers speculate that DNA-binding proteins might recruit H3K9 methyltransferase enzymes, creating the initial mark that subsequently guides DNA methyltransferases. Identifying these upstream factors represents an important direction for understanding how epigenetic memory is encoded during mammalian development.

The work was led by Takuro Horii and Izuho Hatada at Gunma University in Japan. It was published in Nature Communications on 25 December 2025.

To get more CRISPR Medicine News delivered to your inbox, sign up to the free weekly CMN Newsletter here.

HashtagArticleHashtagCMN HighlightsHashtagNewsHashtagEpigenome editing (e-GE)HashtagdCas9