Forty years ago when Dolores Mucu arrived in Carolina, the area in Guatemala’s tropical province of Alta Verapaz was covered in rain forest.

“There used to be a river that ran by the main town area,” she recalls.

Back then, there were streams and creeks around Carolina which local families used for washing and catching fish, says 66-year-old Mucu.

Now, the river has run dry and towering African oil palm trees cover much of the surrounding land. “There’s no water any more because the palm company diverted it,” she says.

Full-grown African oil palm trees stand at over 18m tall with deep roots and produce about 22kg of fruit every few weeks.

Inside the oil palm fruit is a versatile red liquid that is now widely found in processed foods, cosmetics and biodiesel.

Dolores Mucu on the land recently reclaimed from the local palm oil plantation in Carolina. Photograph: Hannah McCarthy

Dolores Mucu on the land recently reclaimed from the local palm oil plantation in Carolina. Photograph: Hannah McCarthy

Amid high global demand, Guatemala is now one of the fastest-growing producers of palm oil outside Southeast Asia. The plantation in Carolina opened in 2011 and initially covered about 14 hectares of land bought from the Guatemalan state.

Residents say that the company offered low-wage jobs with poor conditions and within five years, the plantation expanded into land belonging to the Carolina community, tearing down and burning existing rainforest and underlying peatland.

The loss of humid forests in tropical areas have a particularly harmful impact on climate as they store about a quarter of the world’s carbon emissions, regulate weather systems which have an impact on rainfall and have dense levels of animal and plant biodiversity.

After several years of campaigning and protests, locals in Carolina recently returned to living in one patch of land reclaimed from the oil palm plantation.

“Our children need a place to live,” says Elizabeth Chemax (57). “That’s why we fought for that land – because if we hadn’t, they would have planted even more palm trees.”

As the number of African oil palm trees swelled, local residents say they began to experience water shortages.

Most households in Carolina have a small well, but they now routinely dry up during the increasingly long hot season.

Elisabeth Chemax: ‘people are suffering from strong fevers, with coughing and stomach pain.’ Photograph: Hannah McCarthy

Elisabeth Chemax: ‘people are suffering from strong fevers, with coughing and stomach pain.’ Photograph: Hannah McCarthy

Chemax says that wells located near deep rooted oil palm trees were particularly affected. For the past two years, some households have spent nearly three weeks without any water during the hot season. When that happens, locals are forced to travel to wash themselves and their clothes.

“I almost met death last year,” says Chemax, describing how she nearly drowned while washing clothes in an unfamiliar river in June 2024. “We didn’t really know how deep the water was or where the currents were strong. It looked calm, but the river can be treacherous.”

Chemax says: “We’re suffering so much because of the [dried-up] river [in Carolina].”

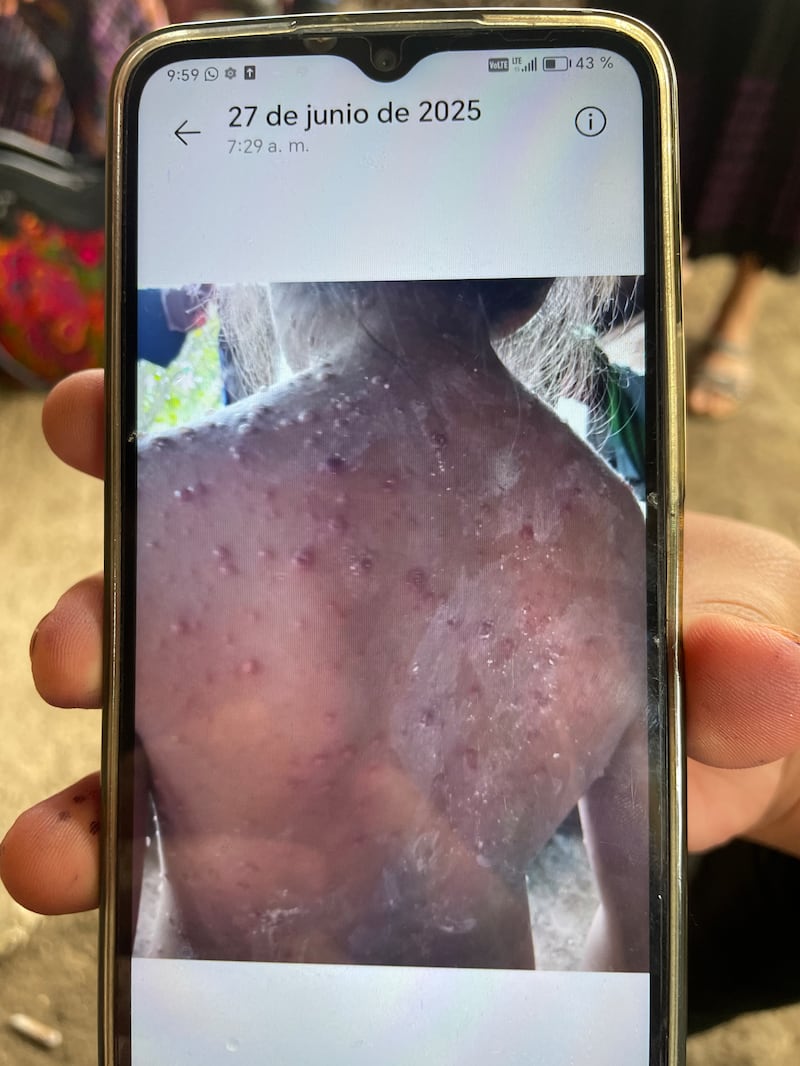

Residents say the lack of water and changes in the climate in Carolina have increased the number of flies and pests and skin diseases are now common.

“In the community, we see that children are getting very sick – so many illnesses,” says Chemax. “These past months there have been lots of fevers. Right now, people are suffering from strong fevers, with coughing and stomach pain.”

Residents say pests and skin diseases are now common. Photograph: Hannah McCarthy

Residents say pests and skin diseases are now common. Photograph: Hannah McCarthy

The expansion of the plantation in Carolina has coincided with a degradation in soil quality.

“Most oil palm, whether grown by large companies or smallholders, is cultivated in intensive monocultures,” says David Gaveau, who founded TheTreeMap, a French company that monitors forests.

“These systems rely heavily on fertilisers and pesticides, which degrade soils, pollute water, and increase vulnerability to pests, deadly fungi and drought.”

“When the summer comes, the ground becomes so hard that we can’t plant anything,” says Chemax. “The corn barely grows. If we use fertiliser, we can harvest a little; if not, nothing comes up.”

According to the World Atlas of Desertification, 75 per cent of the world’s soils are now degraded, with a direct impact on 3.2 billion people. Photograph: Hannah McCarthy

According to the World Atlas of Desertification, 75 per cent of the world’s soils are now degraded, with a direct impact on 3.2 billion people. Photograph: Hannah McCarthy

Fertiliser is unaffordable for many local farmers but in the nearby village of Pecjaba, the Irish NGO Christian Aid is spearheading an agricultural training programme with a local partner called Congcoop to help farmers create their own organic fertiliser.

As part of an effort to reduce deforestation globally, the EU, the world’s third-largest importer of palm oil, enacted the Regulation on Deforestation-free products in 2023. After a delay, the regulation, known as EUDR, is due to start coming into effect at the end of 2025 and will require operators exporting or importing palm oil in the EU to show that it did not originate from recently deforested land.

Under the regulation, if a palm oil exporter from Guatemala includes oil from a single uncertified farm in a consignment that would render the entire lot ineligible for export to the EU.

Lax enforcement and oversight of supply chains, alongside EU incentives for biofuels, has however created an opportunity for operators to mislabel palm oil as used cooking oil, which can be imported as biofuel that will not be subject to the EUDR.

“Biofuels legislation requires certification of the raw material origins by the EU ‘Voluntary Schemes’. But these schemes are not supervised by any public body. They are honour systems that nobody checks,” says James Cogan, an industry and policy adviser for Irish renewable energy manufacturer Clonbio.

The renewables firm said a mistake in a 2024 report from Ireland’s National Oil Reserves Agency shows that the Irish state could have imported millions of litres of palm oil falsely labelled as biofuel in 2024.

Critics of the EUDR have said that the regulation could disproportionately impact small farmholders with expensive compliance obligations.

An official EU briefing document says that farmers can map their land using a smartphone and free-to-use digital applications, such as geographic information systems, but many farmers lack land title documentation.

Tania Li, a professor of social science at National University of Singapore says policymakers should be encouraging smallholders to grow oil palm, rather than corporate plantation. “Smallholders adapt their planting regime to the soil, the climate and everything – and as the climate changes, they adapt. They have to, [in order] to survive,” says Li.

A worker operates a tractor carrying bunches of African oil palm fruit at a plantation in Guatemala. Photograph: Victor J. Blue/Bloomberg/Getty Images

A worker operates a tractor carrying bunches of African oil palm fruit at a plantation in Guatemala. Photograph: Victor J. Blue/Bloomberg/Getty Images

Gaveau says recent research suggests that the use of “forest islands” – or patches of native trees within monoculture plantations – could improve biodiversity and soil quality.

“This kind of palm oil agroforestry could make palm oil genuinely sustainable, both ecologically and economically.”

He says: “Palm oil is an indispensable food ingredient for half of the global population and plays a crucial role in various industrial processes. Moreover, compared to other oil crops, palm oil cultivation requires less land to produce a higher oil yield per hectare, making it a more efficient choice. Switching to alternative vegetable oils would require even more land, leading to further deforestation.”

“The fundamental problem is not the crop. It’s who’s going to grow this crop on whose land, on what basis, and who’s going to profit and who’s going to lose,” says Li.

“[There is] no history of people prospering with the plantation model.”

simon cumbers

simon cumbers

Supported by the Simon Cumbers Media Fund