Louise Bourgeois was 70 when the Museum of Modern Art in New York finally gave her a retrospective in 1982. A portrait was needed for the catalogue, so off she went in a shaggy monkey fur coat to be photographed by Robert Mapplethorpe.

Intimidated by the prospect of being shot by a man famous for his sexual images of nude men, she took with her as a prop Fillette (1968), her garish latex sculpture resembling a gigantic phallus (or a female torso, depending on the angle). In the photo, it’s tucked under her arm like a baguette, and she meets our gaze with a mischievous grin. “I knew that I would get comfort from holding and rocking the piece,” she told a captive audience years later. “Actually, my work is more me than my physical presence.”

That may be so, but, as this meticulously researched and deeply personal biography shows, Bourgeois the little girl, the young woman, the adult is just as captivating and surprising as Bourgeois the artist, most famous for her giant steel spiders.

Written in French by Marie-Laure Bernadac and lucidly translated by Lauren Elkin, Knife-Woman traces Bourgeois’ life and work from her birth in 1911 to her death in 2010. It is the first big biography of the artist and has been written by someone who knew her well; Bernadac had spent time with her and organised several exhibitions of her provocative work.

When Bourgeois died, Bernadac, a curator as well as an author, wanted to write about her to discover what was hiding behind that mischievous grin. “Who was this strong but delicate person, with her keen sense of humour, who escaped all categories and classifications?”

Bourgeois was born on Christmas Day in Paris. “I was a pain in the ass when I was born. To all these people, they had their oysters and champagne and there I came.” The middle child of three, she was beautiful and bright and quickly became her parents’ favourite.

Her grandmother restored and sold tapestries; her grandfather was a granite cutter. “Sewing on one side, sculpture on the other,” Bernadac writes. “Louise’s art came directly from this double maternal inheritance: to repair, restore, carve, cut.” In 1910 her mother and father, Joséphine Fauriaux and Louis Bourgeois, had taken over the family business, dealing in antiques and restoring tapestries, which would give Louise her start in art.

• The best books of 2025 — chosen by our critics

What at first seemed like a happy and privileged childhood became bitter and twisted over time. In her endlessly inventive drawings, paintings, sculptures, and fabric pieces, Bourgeois repeatedly explores themes of abandonment (her father was called up to fight in 1914), the beleaguered body (she never forgot seeing wounded soldiers) and sex (her father had a lengthy affair with the children’s young English nanny).

Her relationship with both parents toggled between love and hate, but Louis bore the brunt. In 1974 she imagined the tyrannised family devouring him for revenge in a visceral installation called The Destruction of the Father. Her abandonment of him was gradual: having grown up in a free-thinking household, she turned to religion as a young woman. She studied maths at the Sorbonne before switching to art, delighting in describing the life-drawing models’ inadvertent erections: “That was how she understood masculine fragility,” Bernadac writes.

In 1938 she met the American art historian Robert Goldwater, and 19 days later they were married. They sailed for New York, where he resumed his job as a professor at New York University, and she fought to be seen as more than his French wife.

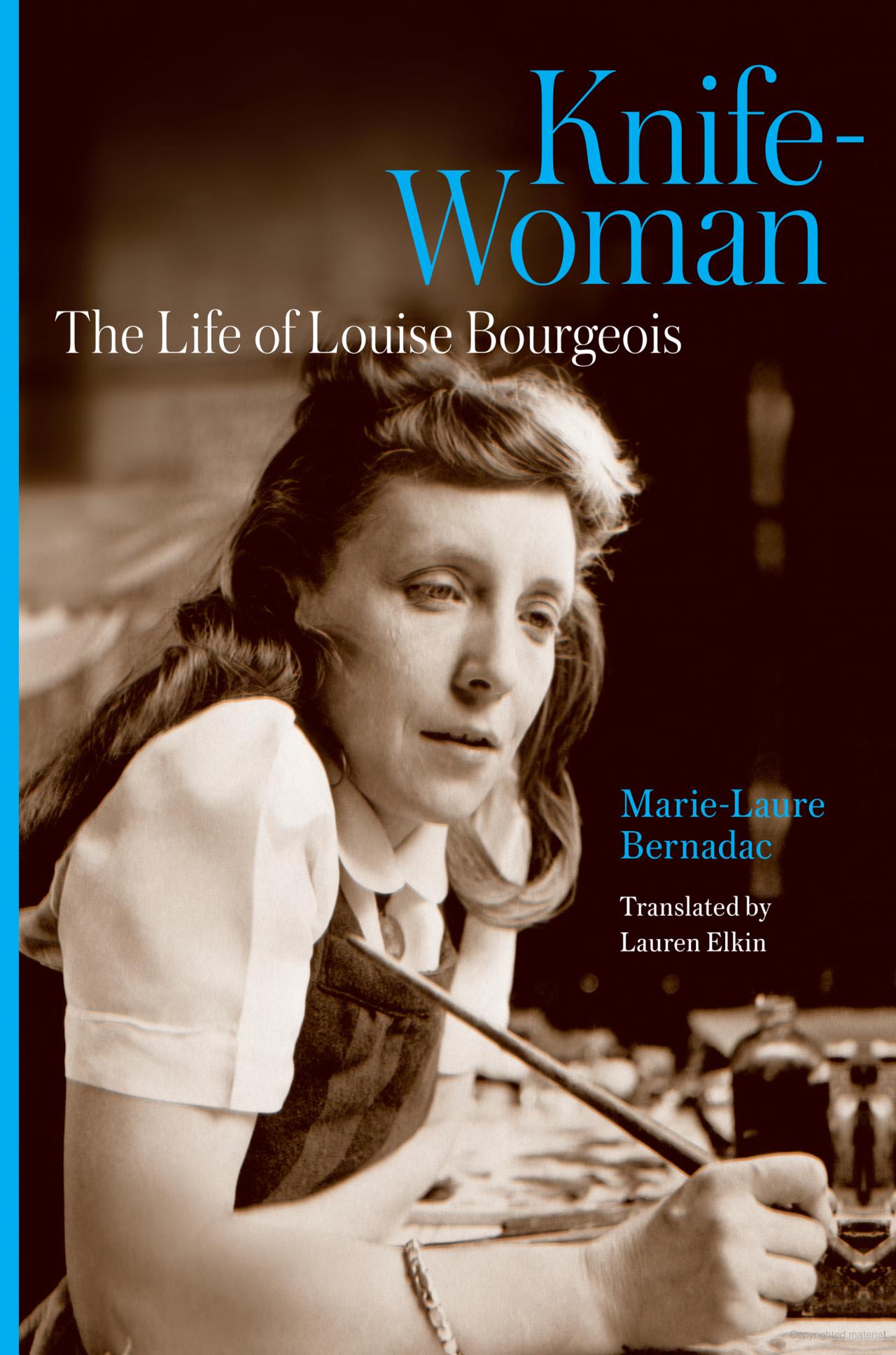

Bourgeois in her New York studio, c 1946

THE EASTON FOUNDATION/VAGA AT ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK

The issue of children was for Bourgeois “the most important one in life”, and in her 1939 diary she tracked the dates of her period, appointments with her gynaecologist and the days she ovulated. Worried that she was infertile, in 1939 she and Goldwater adopted a French orphan, Michel, before going on to have two biological sons, Jean-Louis and Alain. The drawings she made in the 1940s evoke pregnancy, motherhood and a relentless battle between maternal instinct and artistic ambition. She was, she said, “divided inside”, her children “wild beasts” who clung to her skirts and kept her from working.

Soon after Bourgeois’ death, her vast archive was made available. What a treat it must have been for Bernadac. The best bit about this cradle-to-grave narrative is how present, and deliciously unfiltered, Bourgeois is on the page. A compulsive writer, she kept a diary from the age of 11, obsessing over feelings of anxiety, love, depression, jealousy and shame in a mix of French and English — as Bernadac puts it, “her own Franglais”. She kept everything: those diaries, family letters and the psychoanalytic texts she wrote during long-term analysis in the 1950s and 1960s.

• Read more book reviews and interviews — and see what’s top of the Sunday Times Bestsellers List

In New York she found herself surrounded by artists and writers, whom she regularly bad-mouthed — a reaction, maybe, to a macho environment and her thwarted efforts to find a gallery as a young artist and a mother.

Marcel Duchamp, she wrote, “looked very fine and debonair, but he suffered like a dog”. Although she admired Francis Bacon’s work, she felt his face was “fat, squashed and contorted as if someone had sat on an overripe melon”. As for Joan Miró’s assemblages: “There is more to sculpture than a blob of clay with a fork in it.”

Basically, Bourgeois liked only those who liked her work. “My knives are like a tongue — I love you, I hate you. If you don’t love me, I am ready to attack.” And although she had admirers, it was not until the MoMA retrospective that she took her rightful place among the most daring and original artists of the 20th century.

Her sculpture Maman (1999) at Tate Modern

MIKE KEMP/IN PICTURES/GETTY IMAGES

From the 1990s onwards, everyone wanted to show her work. She represented the US at the Venice Biennale in 1993, and in 2000 was the first artist to command the cavernous Turbine Hall at Tate Modern with one of her looming spiders. People wanted to interview and film her. “Every time, she found the filming inconvenient, but every time, she took wicked pleasure in it,” Bernadac writes.

Bourgeois lived to 98 and made outlandish art until the very end. In her words: “My early work is the fear of falling. Later on it became the art of falling. How to fall without hurting yourself. Later on it is the art of hanging in there.”

Knife-Woman: The Life of Louise Bourgeois by Marie-Laure Bernadac, translated by Lauren Elkin (Yale £30 pp472). To order a copy go to timesbookshop.co.uk. Free UK standard P&P on orders over £25. Special discount available for Times+ members