A new study published on the pre-print server arXiv is shedding fresh light on one of the galaxy’s strangest high-energy objects. Using the powerful VERITAS telescope array, a team of astronomers has revisited HESS J1857+026, a mysterious gamma-ray source discovered in 2008 , and uncovered new details that bring us closer to understanding what powers this enigmatic cosmic emitter.

A Gamma-Ray Mystery Lingers Since 2008

First discovered by the High Energy Stereoscopic System (HESS) in 2008, HESS J1857+026 belongs to a class of very high energy (VHE) gamma-ray sources that remain poorly understood. While many such sources are linked to known cosmic phenomena like blazars or binary systems involving compact objects, this one stands apart. Despite being located near the pulsar PSR J1856+0245, no associated supernova remnant (SNR) or extended structure has ever been clearly identified in X-rays or other wavelengths.

That lack of clear counterparts has kept astronomers guessing for more than 15 years. Was the gamma-ray emission coming from the pulsar? From an unseen nebula? Or could it be something entirely different? The absence of conclusive evidence has kept HESS J1857+026 firmly in the “unidentified” category, until now.

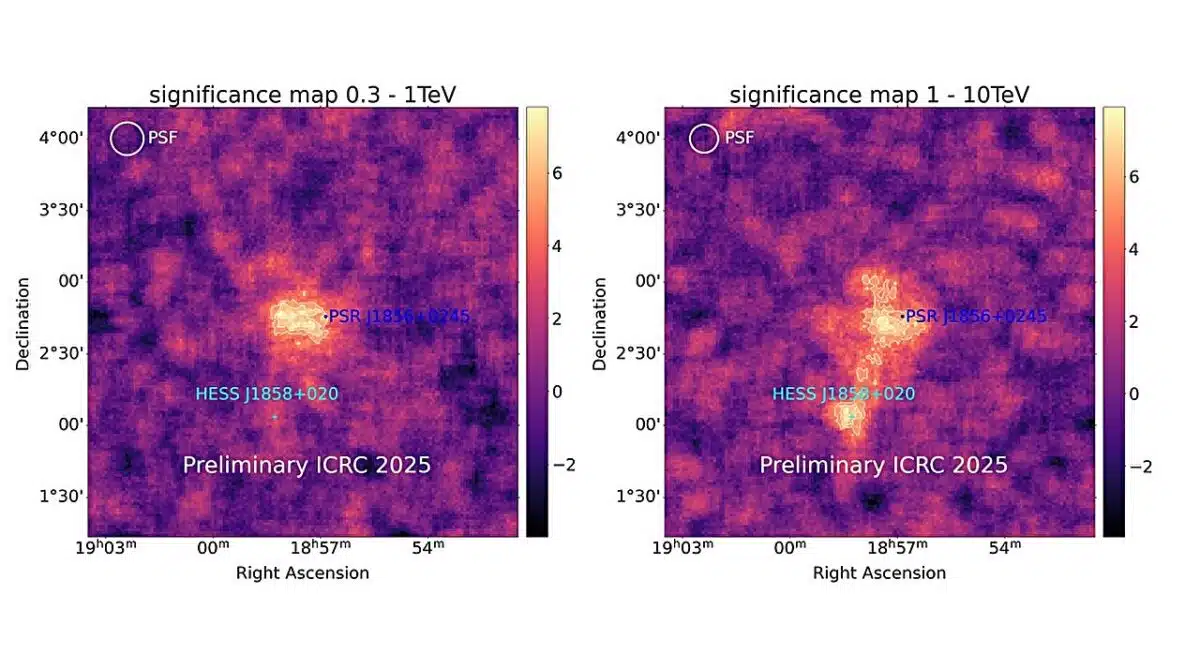

Significance map of region around HESS J1857+026 in 0.3–1 TeV (left) and in 1–10 TeV (right). The white contours represent significance values of 5, 6, and 7 𝜎. The blue dot marks the location of PSR J1856+0245. Credit: Chen et al., 2025.

Significance map of region around HESS J1857+026 in 0.3–1 TeV (left) and in 1–10 TeV (right). The white contours represent significance values of 5, 6, and 7 𝜎. The blue dot marks the location of PSR J1856+0245. Credit: Chen et al., 2025.

Deep Observations With VERITAS Reveal Structural Complexity

To investigate further, a team led by Yu Chen of UCLA turned to the Very Energetic Radiation Imaging Telescope Array System (VERITAS), a powerful array of four gamma-ray telescopes located at the Fred Lawrence Whipple Observatory in Arizona. VERITAS is designed to detect gamma rays in the range of 100 GeV to beyond 30 TeV, with a sharp angular resolution of under 0.1 degrees at 1 TeV.

“VERITAS has observed the region of HESS J1857+026 from 2008 to 2016, including serendipitous observation of other targets, e.g., the supernova remnant W44, in the FOV [field-of-view]. After quality selection requiring good weather and a stable trigger rate, about 30 hours of data are used in this analysis,” the researchers explain.

The findings, published on arXiv on December 19, include a detailed gamma-ray significance map of the region. What stands out is that the strongest emission center appears displaced from the location of the nearby pulsar. This spatial offset adds weight to a long-standing hypothesis: that the gamma rays may not come directly from the pulsar itself, but from a pulsar wind nebula (PWN), a cloud of high-energy particles blown outward by the pulsar’s magnetic field.

A Northern Component Suggests More Than One Source

Perhaps the most surprising aspect of the VERITAS data is the discovery of a northern component in the emission profile. This structure only appears at energies above 1 TeV and could mean one of two things: either there is a second, separate gamma-ray source in the area, or the emission region of HESS J1857+026 is larger and more complex than previously thought.

The researchers calculated that the diffusion length, the distance high-energy electrons travel before losing energy, is roughly 321 light-years. They also estimate that the cooling time for these electrons is on the order of tens of thousands of years. Both values are significant. The long cooling time suggests that the energetic electrons have persisted over time scales comparable to the age of the pulsar, and the low diffusion rate, an order of magnitude lower than the galactic average, indicates something is slowing the spread of these particles.

This points again to a possible PWN scenario, but one that is more extended and slower-evolving than models typically predict.

A Case That’s Still Wide Open

Despite the progress made, the study does not settle the debate about the true nature of HESS J1857+026. While the pulsar wind nebula hypothesis remains the front-runner, the presence of the additional northern structure and the offset emission raise fresh questions. Could there be two overlapping sources? Are we seeing the result of complex shock interactions in the surrounding interstellar medium? Or might an entirely new class of gamma-ray object be hiding in plain sight?

The authors emphasize that more observations are needed, particularly at multiple wavelengths. Future data from instruments like the Cherenkov Telescope Array (CTA) and next-generation X-ray telescopes could offer the resolution and sensitivity needed to disentangle the competing theories.

For now, HESS J1857+026 remains a mystery, but thanks to VERITAS, it’s a mystery that’s beginning to give up its secrets.