PORTLAND, Maine — Grace Hartigan “cursed like a sailor, often dressed in men’s clothing, and prized work over family life,” says the Museum of Modern Art’s frankly riveting short online biography of the mostly-forgotten mid-20th-century American painter. In simplest terms, she did what she had to — to work, to paint, to scrape together a career in a time and place, 1950s New York, dominated by the burgeoning all-American machismo of Abstract Expressionism. Its biggest names — Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline — all drank and smoked and swore and drank some more; to be even mildly demure was to be set aside, like most of their equally talented partners and spouses: the artist Lee Krasner, Pollock’s long-suffering wife, whose painting career suffered along with her; Elaine de Kooning, a remarkable painter and writer herself. Both would be largely subsumed by their partners’ out-loud ambitions, only to be rediscovered many years later. Hartigan would defer to no one, come what may.

What didn’t come was success — materially, at least. But Hartigan set a different path, and on her own terms. It brought little in the way of renown — or money; she was resolutely poor — but paid her back in kinship and a creative blossoming all her own. “Grace Hartigan: The Gift of Attention,” now on view at the Portland Museum of Art, follows that path from 1952 to 1968, the most fertile span of her creative life. It tells us much about not only her unlikely journey, from teen mom in 1940s Newark to the center of the American art world, but also reminds us how much of American culture has been pushed aside by its dominant strains, and the riches to be discovered amid those, like Hartigan, relegated to the fringes.

A viewer with Grace Hartigan’s “Dido,” 1960, at the Portland Museum of Art.Courtesy of Portland Museum of Art

A viewer with Grace Hartigan’s “Dido,” 1960, at the Portland Museum of Art.Courtesy of Portland Museum of Art

Just inside the exhibition, Hartigan’s 1952 piece “The Persian Jacket” all but seems to quiver in a warm pool of light. It’s both her breakthrough and the point of departure that would take her far from the mainstream current of popular appeal. Acquired the next year by Alfred Barr, MoMA’s director and the chief supporter of the AbEx movement, the piece is alive with Hartigan’s exuberant brush strokes — rough, deliberate swipes of red, a whirl of orange, jagged slashes of white, all on a background of heavy smears of black. But the piece was not abstract, the dominant ethic of the moment; a face, a hand, a seated figure all emerge from the murk. While the AbEx crew was straining to craft their own version of pictorial purity, Hartigan was looking to old masters, like Velazquez. On the threshold of renown, she was already pulling away.

It makes sense. Convention hardly suited her. Hartigan’s story could be a pulp fiction novel: Born working class in Newark in 1922, she got married at 17, right out of high school, and had her first child, a son, less than a year later. When the United States entered World War II in 1941, she started working as a mechanical draftsman in an airplane factory while her husband fought overseas. With a toddler at home and her husband across the ocean, she took night courses at a local engineering college, where a classmate first showed her pictures of paintings by the revolutionary French painter Henri Matisse. She was, in her own words, “hooked,” and dropped everything for art — including her husband. She took up with her new painting teacher, Isaac Lane Muse, and she and her son moved to Manhattan with him in 1945, where the AbEx revolution was quickly gaining momentum.

Grace Hartigan, “The Persian Jacket,” 1952, at the Portland Museum of Art.Murray Whyte/Boston Globe

Grace Hartigan, “The Persian Jacket,” 1952, at the Portland Museum of Art.Murray Whyte/Boston Globe

Hartigan became an habitué of the Cedar Tavern, the Greenwich Village hub of the AbEx crowd; MoMA was barely 15 years old, a radical upstart that was quickly morphing into the platform that would make Abstract Expressionism the dominant global movement of its time. Hartigan appealed to Pollock and Krasner for help, and became friendly with the de Koonings. Living lean on “oatmeal and bacon ends,” according to a 2015 book on her life, painting was everything and all. She began showing as “George Hartigan,” surely an attempt to sidestep the disdain women artists often received when exhibiting their work in public — Louise Nevelson, an eventual doyenne of the downtown scene, could tell her all about that. But their painting, with its muscular slashes and swipes of raw energy on canvas, was not her painting, and she was always destined to break away.

When MoMA acquired “The Persian Jacket,” neither Krasner nor Elaine de Kooning had been given much of a serious look by major museums. That made Hartigan a first, and her departure all the more puzzling. In Portland, wildly accomplished works like “Orange Field,” 1958, a fiery 7-foot-tall canvas of tangerine scarred by expressive slashes of dark blue, yellow, black, and green, come close to raw abstract fury; Hartigan intended it as a landscape. Across the room, “East Side Sunday,” 1956, shrugs off any doubt about her intentions. Boxes of lemons and limes, as seen from her Lower East Side studio window of the fruit stand below, emerge from an explosion of painterly bliss. Nearby is “Grand Street Brides,” 1954, a wholly figurative vision of mannequins decked out in a bridal shop window in her gritty urban neighborhood. A huge canvas overcome in heavy shades of black and gray, its loose contours and heavy strokes of paint freight it with expressive unease. “I have found my ‘subject,’” she once declared. “It concerns that which is vulgar and vital in American modern life.”

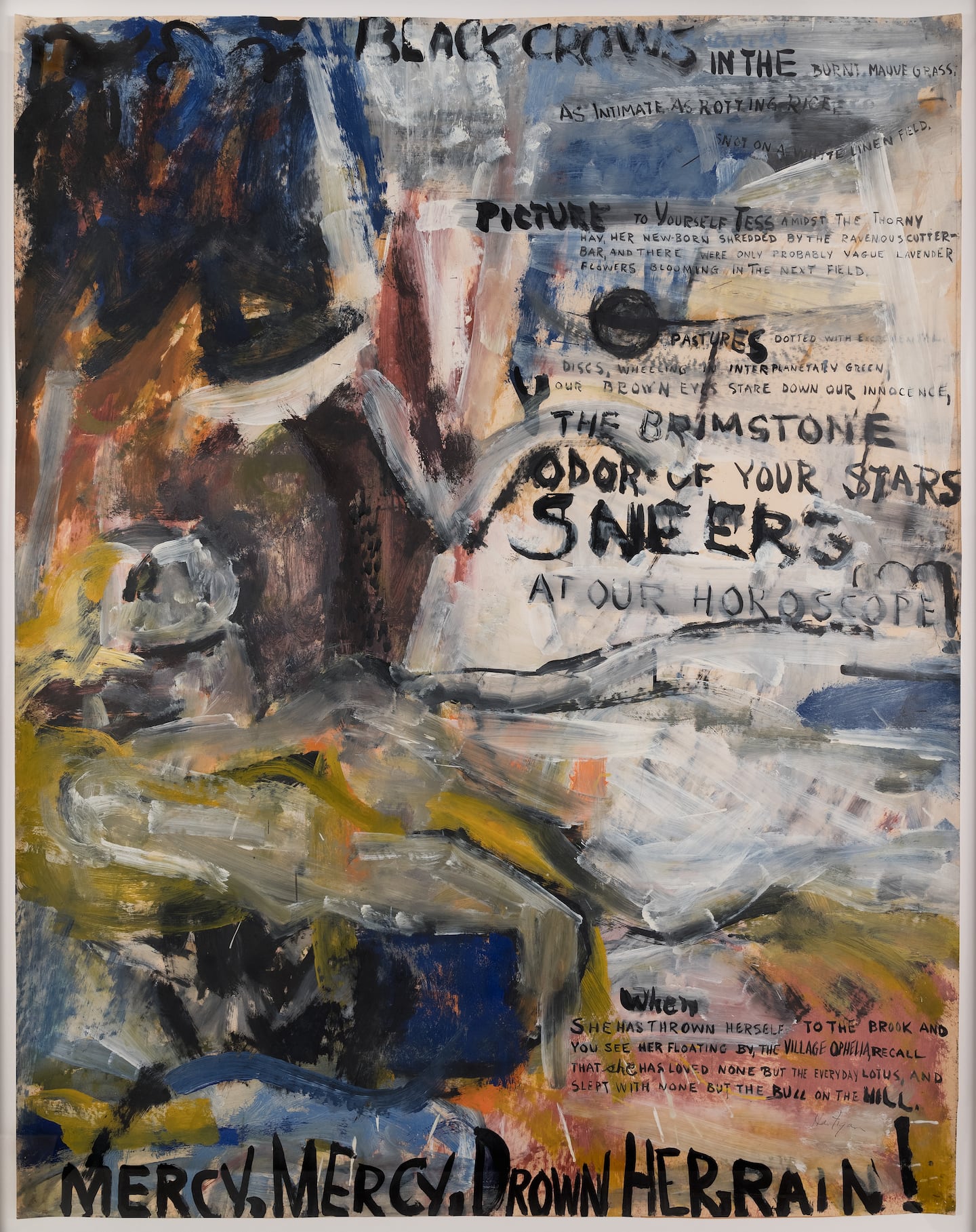

Grace Hartigan, “Black Crows (Oranges No. 1),” 1952. University of Buffalo Art Galleries. Nicholas Ostness

Grace Hartigan, “Black Crows (Oranges No. 1),” 1952. University of Buffalo Art Galleries. Nicholas Ostness

Hartigan found her creative home in the downtown poetry scene that would catalyze much of her most satisfying work. The poet Frank O’Hara had helped connect her with Barr, after Hartigan had produced “Black Crows (Oranges No. 1),” in 1952, a vibrant fusion of her energetic brushwork and his spare, haunting text (“Oranges” was the name of a series of his poems.) It might be the best thing here, and that’s saying something: Snippets of text float in the wash of her heavy painterly gestures, a haunting convergence of the particular and the ineffable. She had found her calling.

Hartigan took refuge in her poetic milieu — O’Hara, of course; James Schuyler, who had written favorably about her painting in the art press; James Merrill, the poet and scion of Charles Merrill, the Merrill Lynch cofounder, who helped promote and finance her work. But none catalyzed her creative fire like Barbara Guest, who would become a close collaborator in the 1960s. “The Hero Leaves His Ship,” her first crossover with Guest in 1960, is a series of black and white ink drawings matched to her poetry series of the same name. Visceral and spare in black and white, they’re as wildly alive as anything here.

Grace Hartigan, “Dido,” 1960. Collection of The McNay Art Museum. Courtesy of Portland Museum of Art

Grace Hartigan, “Dido,” 1960. Collection of The McNay Art Museum. Courtesy of Portland Museum of Art

Guest’s fascination with classical mythology tethered Hartigan to firm ground. Character and story nurtured something in her that abstract purity could not. She remained loose, exuberant, oblique; “Dido,” 1960, drawn from Guest’s reading of the tragedy of Dido, abandoned by Aeneas and dead of a broken heart, is a fog of melancholic gloom, deep blue adrift in a sea of angry red, collapsing in its center.

But it meant something specific, as her work always would — maybe never more than with “The Hero,” 1960, with its steel-gray haze climbing up from the canvas’s lower reaches, swallowing the bright chaos above. Another riff on Guest’s poem, it embodied the hero’s journey into the unknown; but Hartigan, newly married to a Baltimore epidemiologist and art collector and soon to leave her beloved New York poetry world for good, was untethered — the hero of her own life’s story, once again adrift.

GRACE HARTIGAN: THE GIFT OF ATTENTION

Through Jan. 11. Portland Museum of Art, 7 Congress Square, Portland, Maine. 207-775-6148, portlandmuseum.org

Murray Whyte can be reached at murray.whyte@globe.com. Follow him @TheMurrayWhyte.