Sign up for the Starts With a Bang newsletter

Travel the universe with Dr. Ethan Siegel as he answers the biggest questions of all.

Out there, in the vast Universe, are clumps of matter that come in many different sizes and masses. We might be most familiar with galaxies like our Milky Way: with hundreds of billions of solar masses worth of stars, even more gas and plasma, and more than a trillion solar masses worth of dark matter. At smaller masses, however, it takes longer, and becomes more and more difficult, for clouds of normal matter to collapse. If these low-mass clumps of matter do collapse, they’ll form stars, with the radiation from those stars often blowing the remaining gaseous matter away, but it’s also possible that — with enough externally injected energy — those clumps will never collapse.

That’s the idea behind what astronomers call a RELHIC: a Reionization-Limited HI Cloud, or a cloud of neutral hydrogen found within a more massive dark matter halo that’s in thermal equilibrium with the cosmic ultraviolet background. Although starless gas clouds have been found before, they:

- are usually rotating, indicating the presence of a collapsed disk,

- are typically high in mass, of around 100 million solar masses or more,

- and have fairly weak limits on how few stars could be located inside, usually not dropping below 100,000 solar masses worth of stars.

But with the discovery of a new starless gas cloud known as “Cloud 9,” coupled with deep Hubble imaging of that same field-of-view, we just might have stumbled upon the first RELHIC known to humanity. Here’s what we’ve found, plus the story of what it all means.

Discovered back in 1781, galaxy Messier 94 is one of the closest and brightest galaxies to Earth: located a mere 16 million light-years away. Its main disk is further surrounded by sweeping spiral structures that are actually forming the majority of stars within this galaxy at present.

Credit: R Jay Gabany (Blackbird Obs.)

First, let’s start with “Cloud 9” itself, and what makes it such an interesting find. Above, you can see the galaxy Messier 94: a close, bright, massive galaxy located just 16 million light-years away. Although it’s marginally smaller than the Milky Way, there are around 20 known satellite galaxies around it, all of which contain significant quantities of stars and which appear to be gravitationally bound to Messier 94 itself.

That’s probably only the tip of the proverbial iceberg, however. It’s very likely that there are more satellite galaxies around Messier 94, as the nearest galaxies with the highest-resolution imagery show evidence for there being anywhere from 30-100 small satellites for every Milky Way-like galaxy that’s out there.

To search for these suspected additional satellites, researchers in China took the world’s largest ground-based radio telescope — FAST, or the Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical radio Telescope — and surveyed the area around Messier 94 in a comprehensive fashion back in 2023. In addition to confirming the presence of the already-known satellites around it, it discovered several new satellite candidates by detecting the hydrogen gas within them.

This 2025 image shows the largest single-dish radio telescope in the world: the Five-hundred-meter Spherical Aperture Telescope, or FAST. Full completed in 2020, it surpassed the previous record-holder, Arecibo, which collapsed in December of that year. FAST now stands alone as the only radio telescope in its class.

Credit: SCJiang/Wikimedia Commons

Most of those detected gas clouds corresponded to large masses of gas: of tens of millions (or more) of solar masses worth of neutral hydrogen. But one of them — the ninth one found by FAST — had a large, extended distribution of neutral hydrogen gas, but only a small amount of it. Spanning over 4000 light-years in extent, it contained “only” around one million solar masses of neutral hydrogen. And, perhaps even more remarkably, the other imaging we had conducted of that region, including with a variety of optical, infrared, and radio telescopes, showed no conclusive evidence for the presence of stars within that gas cloud at all.

That caught the interest of a wide variety of astronomers, and led to an interesting follow-up project: to deeply view this region of space with not just other radio telescopes, but to acquire deep imaging of it with the Hubble Space Telescope. This would enable us to see if “Cloud 9” was truly a starless gas cloud, to the limits of our ability to observe small numbers of stars at a distance of 16 million light-years, or whether there were actually stars inside of it after all, and whether this was only initially designated as a potentially starless cloud because our observations simply weren’t of sufficiently high quality.

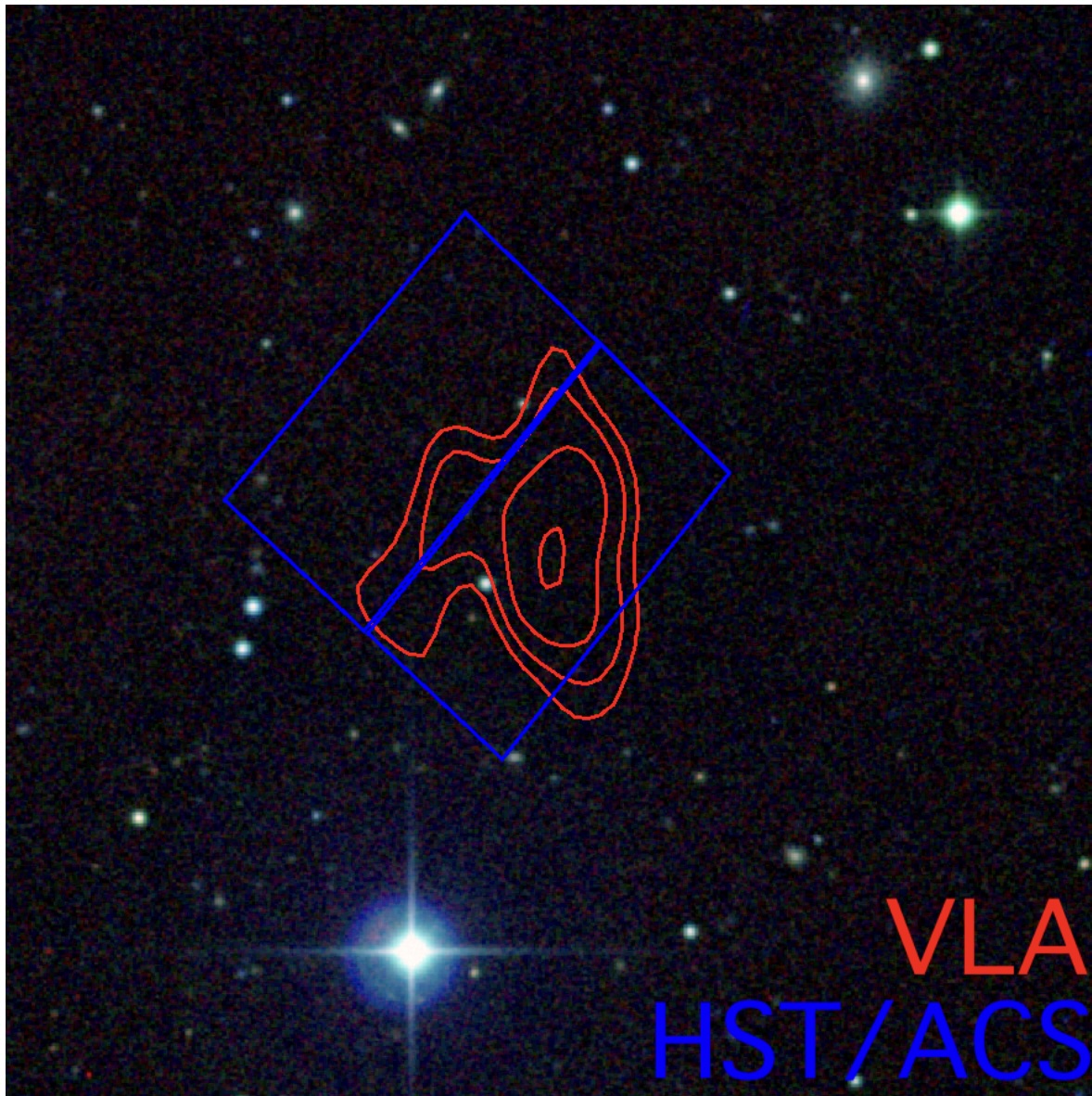

This overlay shows the region where “Cloud 9” on the outskirts of Messier 94 is located, with the detection of neutral hydrogen from the Very Large Array shown in red contours. The Hubble imagery was conducted primarily in the blue boxed regions, yet failed to deliver a detection of any stars co-identifiable with that object across the entirety of its observations.

Credit: G. Anand et al., Astrophysical Journal Letters, 2025

It’s not as straightforward a task as it might seem. You might think, “oh, all I’ll have to do is take my high-quality observations, see if there are any individual stars revealed by those observations, and then, if there are, to infer what to total mass of stars is given the distance that this object is at.”

But the reality is much more complicated. At a distance of 16 million light-years, this could easily be a faint dwarf galaxy, particularly a low-surface-brightness galaxy, whose stars are simply beyond the limits of telescopes to resolve. When a ground-based telescope can’t detect stars above the overall background sky brightness, it’s enough to limit the total mass in stars to a few hundred thousand solar masses for an object like Cloud 9.

By going to space, however, there’s no longer any atmospheric/all-sky brightness to contend with. Hubble imagery can reveal, in the same location where the radio data indicates the greatest densities of hydrogen gas, whether there are any detectable stars or not. If there are stars that appear in that data, then we can use a mix of direct observations and simulations to infer what the overall stellar mass of that region is.

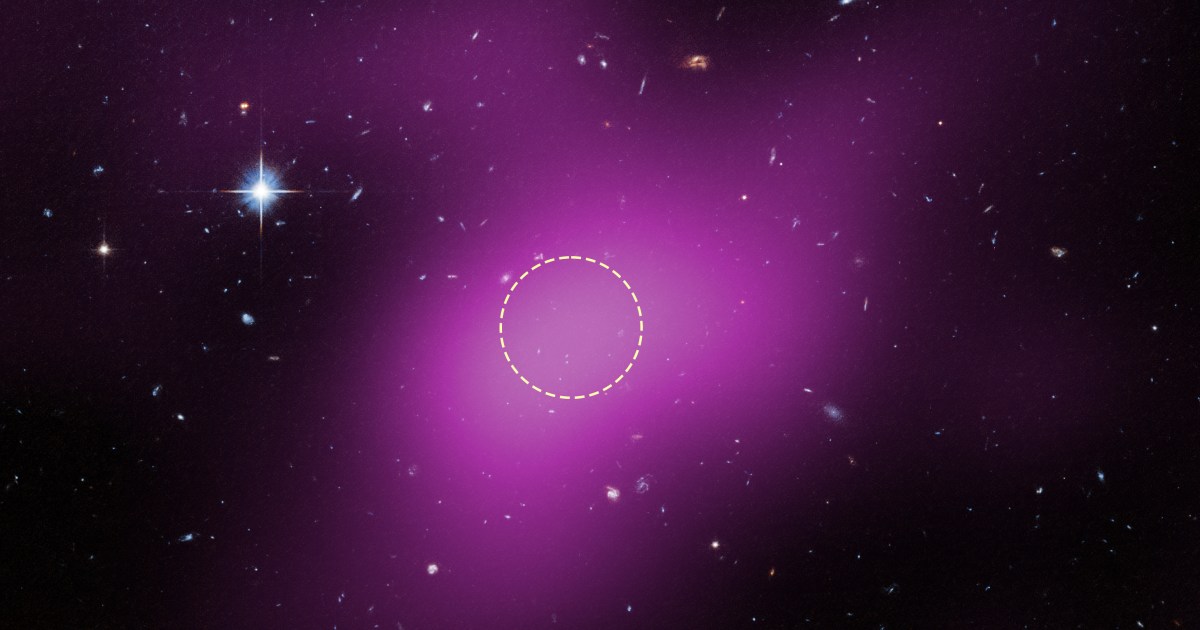

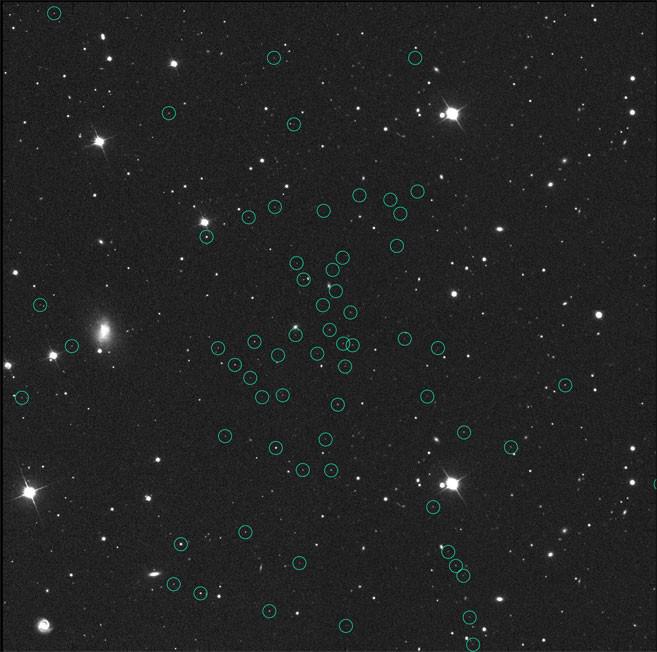

This animated image shows the raw Hubble field of the region centered on the location of “Cloud 9” on the outskirts of Messier 94, with data from the Very Large Array superimposed in pink atop it, showing the density of neutral hydrogen. No stars can be identified within the relevant area of interest.

Credit: NASA, ESA, VLA, Gagandeep Anand (STScI), Alejandro Benitez-Llambay (University of Milano-Bicocca); Image Processing: Joseph DePasquale (STScI)

But if no stars appear, we can use what we learn from those observations and simulations to place an upper limit on how many stars could possibly be contained within that region. As you can see, from the VLA data overlaid atop the raw Hubble image of the field, there doesn’t appear to be any evidence for the presence of stars in the region of interest highlighted here.

In fact, there are several features that make Cloud 9 such a compelling candidate for being a reservoir of hydrogen gas that has never formed stars throughout its history. They include:

- the fact that it recedes from us at a speed of just over 300 km/s, the precise same speed that Messier 94 recedes from us,

- the fact that it’s located around 250,000 light-years from Messier 94,

- the fact that it exhibits such a strong signature of neutral hydrogen without any stars,

- and the fact that, to have all of this hydrogen present with no stars, a significant “halo” of dark matter, in excess of a billion solar masses, must be present.

You see, if you have a dark matter halo with neutral hydrogen gas within it, if it were in total isolation, you’d expect to form stars so long as you had enough mass gathered together in one place. When the astronomers who researched this gas cloud brought the Hubble imagery data together with the rest of the observations that had been acquired, however, they were able to place very tight constraints on the stellar populations that were allowed inside.

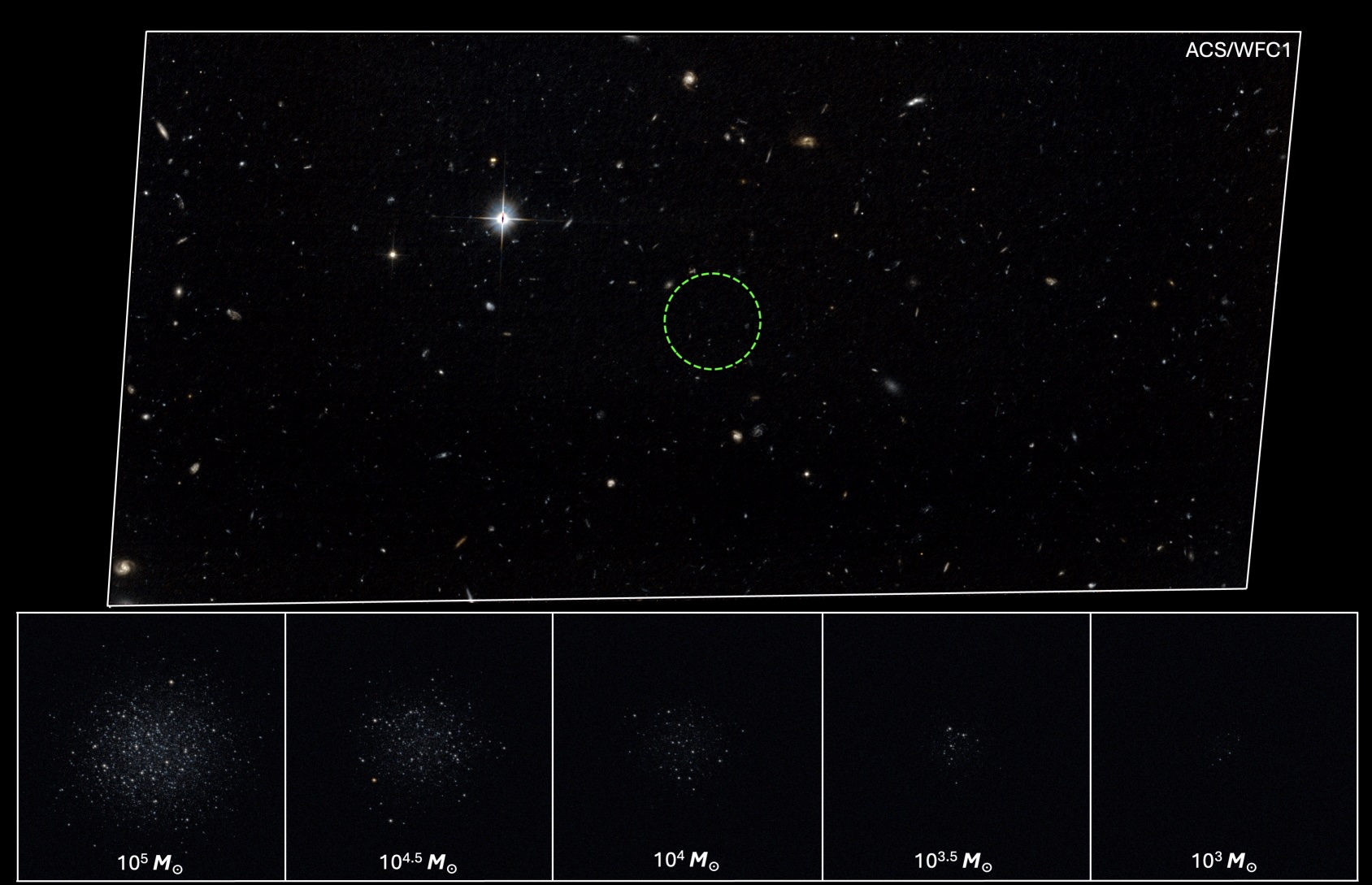

The raw Hubble image of the region around the allegedly starless gas cloud “Cloud 9” fails to show any evidence for stars at all. The expected signals that should have shown up for a variety of stellar masses, from around 300,000 solar masses down to around just 1000 solar masses, as shown from left-to-right at the bottom of the image above, strongly favors the lowest stellar mass contents for this object.

Credit: G. Anand et al., Astrophysical Journal Letters, 2025

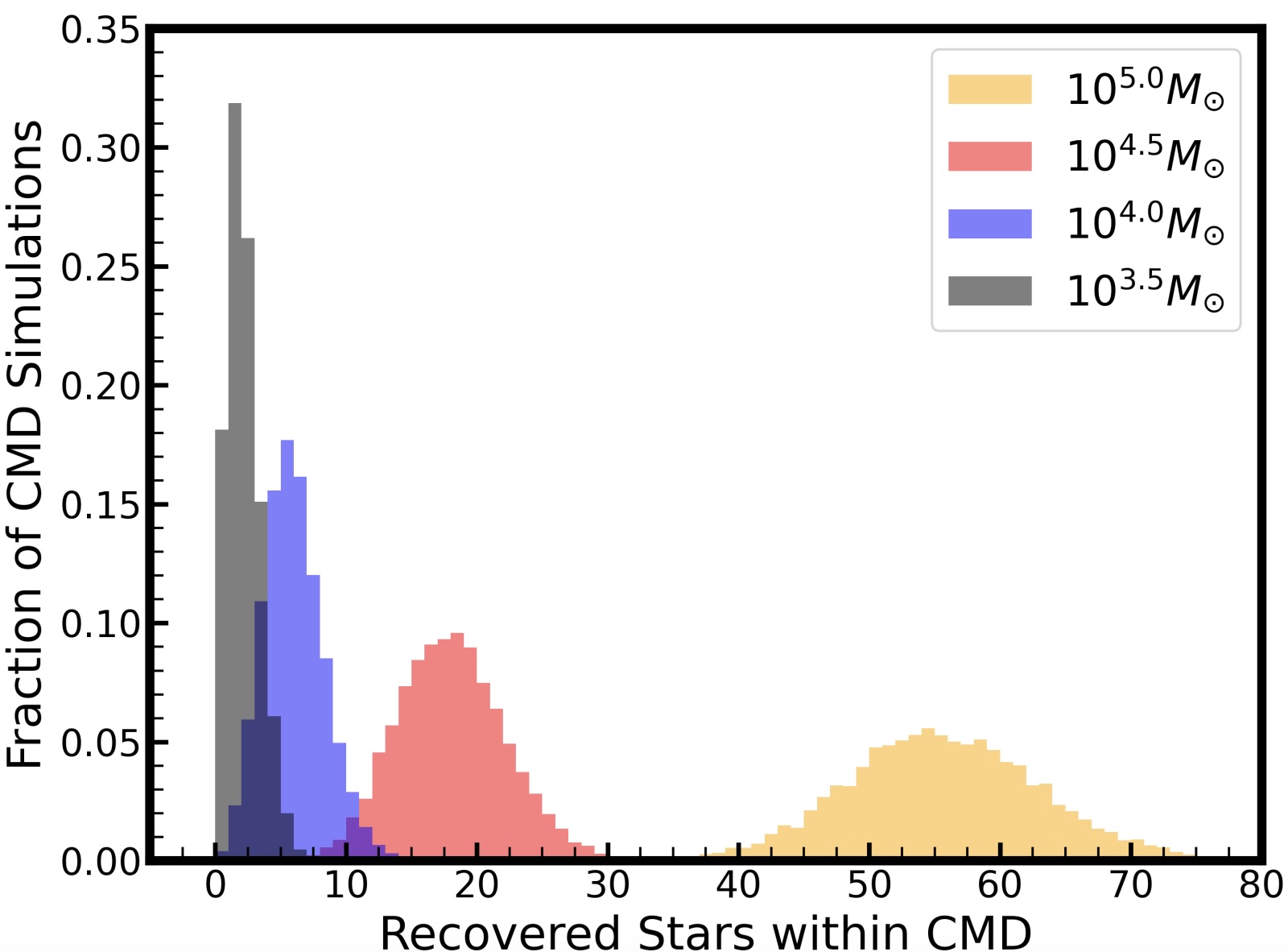

With ground-based imaging, we could only say, “well, there aren’t many hundreds of thousands of stars in there,” but we weren’t able to place any tighter constraints than that. With Hubble imaging, however, they were able to rule out stellar masses of 100,000, of 30,000, of 10,000, and even of 3,000 solar masses. All told, it looked like no more than about 1000 solar masses worth of stars could exist inside of this object: a remarkably small figure given a million solar masses of neutral hydrogen gas present within this gas cloud.

The way the researchers went about determining constraints on the allowable masses for the stars inside was to simulate the following:

- if we had this number of total stars inside of it,

- then what would the range of the number of individual stars be that appeared in the Hubble data,

- and, given that we have seen at most 1 excess star (above the normal background) in the Hubble data and given what we know about the color/magnitude of stars, how significantly can we rule out the higher stellar mass values?

At greater than 5-σ significance (the gold standard for astrophysics and particle physics science), stellar masses above 10,000 solar masses are ruled out entirely. Stellar masses of 10,000 solar masses are ruled out at the 99.5% confidence level (around 3-σ), and stellar masses around 3000 solar masses are ruled out at about the 95% (or 2-σ) confidence level.

Simulated numbers of excess stars that should appear within the CMD region of Cloud 9 as viewed with the Hubble Space Telescope. Because there is at most 1 excess star over the background, these simulations can rule out stellar masses of 10^5, 10^4.5, and 10^4 solar masses quite robustly. 10^3.5, or around 3000 solar masses, is about the highest allowable stellar mass that remains consistent with the Hubble observations.

Credit: G. Anand et al., Astrophysical Journal Letters, 2025

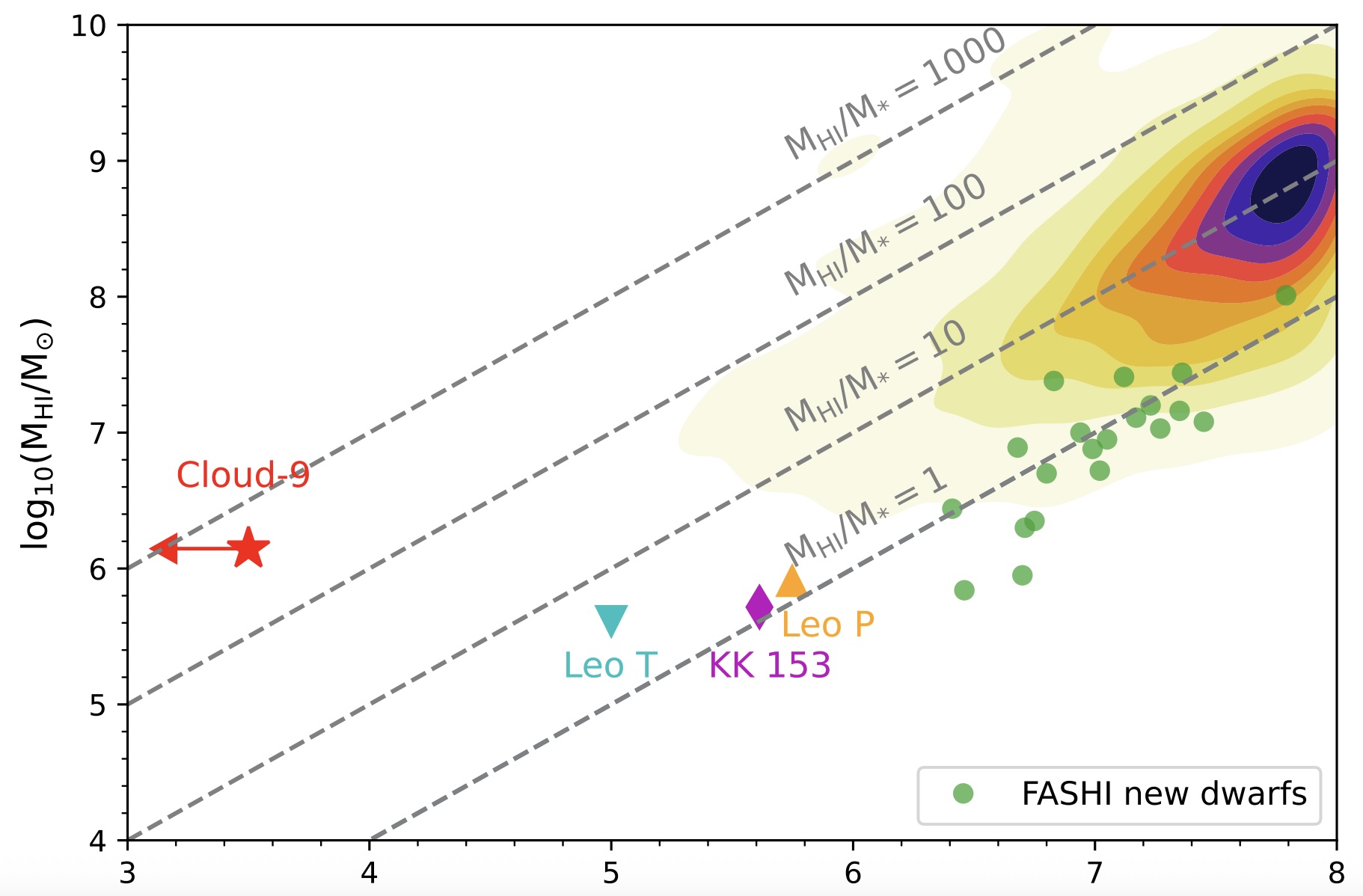

With this detailed analysis, supported by a visual inspection of the Hubble data, the researchers rightfully conclude that this object, Cloud 9, observed (with the Green Bank Telescope) to have 1.4 million solar masses worth of neutral hydrogen, can have no more than about 3000 solar masses worth of stars. That’s a ratio of more than 400:1 in terms of gas-to-stars, which is a tremendous outlier among dwarf galaxies.

Typically, what happens is:

- a large, massive dark matter halo,

- also draws in large amounts of gas,

- then when enough of that gas accumulates in one place, it cools and collapses,

- and that collapse leads first to a disk and then to the formation of stars,

- and those stars, if they’re massive and energetic enough, blows the rest of the gas out of the galaxy,

- leaving only a series of stars embedded in a deep dark matter halo.

We see this for all sorts of dwarf galaxies in the nearby Universe, including for galaxies like Segue 1 and Segue 3, which are nearby galaxies with the lowest stellar mass contents — of only a few hundred (or perhaps up to 1000) solar masses — while displaying relative speeds (or velocity dispersions) that indicate hundreds of thousands of solar masses worth of dark matter. It’s by contrasting this new object, Cloud 9, with the previously known (and more common) dwarf galaxies that we find in the Universe, that we can truly see how remarkable Cloud 9 is.

Only approximately 1000 stars, totaling ~175 solar masses, are present in the entirety of dwarf galaxies Segue 1 and Segue 3, the latter of which has a gravitational mass of an impressive 600,000 Suns. The stars making up the dwarf satellite Segue 1 are circled here. As we discover smaller, fainter galaxies with fewer numbers of stars, we begin to recognize just how common these small galaxies are as well as how elevated their dark matter-to-normal matter ratios can be; there may be as many as 100 for every galaxy similar to the Milky Way, with dark matter outmassing normal matter by factors of many hundreds or even more.

Credit: Marla Geha/Keck Observatory

That’s because this standard “story” we tell about dwarf galaxies corresponds to the overwhelming majority of dwarf galaxies that we’ve found. However, there’s another possible story to their evolution as well. In this scenario:

- you begin with a dark matter halo,

- and large amounts of neutral hydrogen fall into it,

- but the hydrogen remains diffuse and has difficulty cooling,

- largely due to the presence of ultraviolet radiation from all the stars formed throughout the cosmos (i.e., the cosmic ultraviolet background),

- which gradually ejects some (or most) of the hydrogen gas inside,

- leaving only a small reservoir of hydrogen inside a large, massive dark matter halo,

- where only a small number, or perhaps even zero, stars have formed inside.

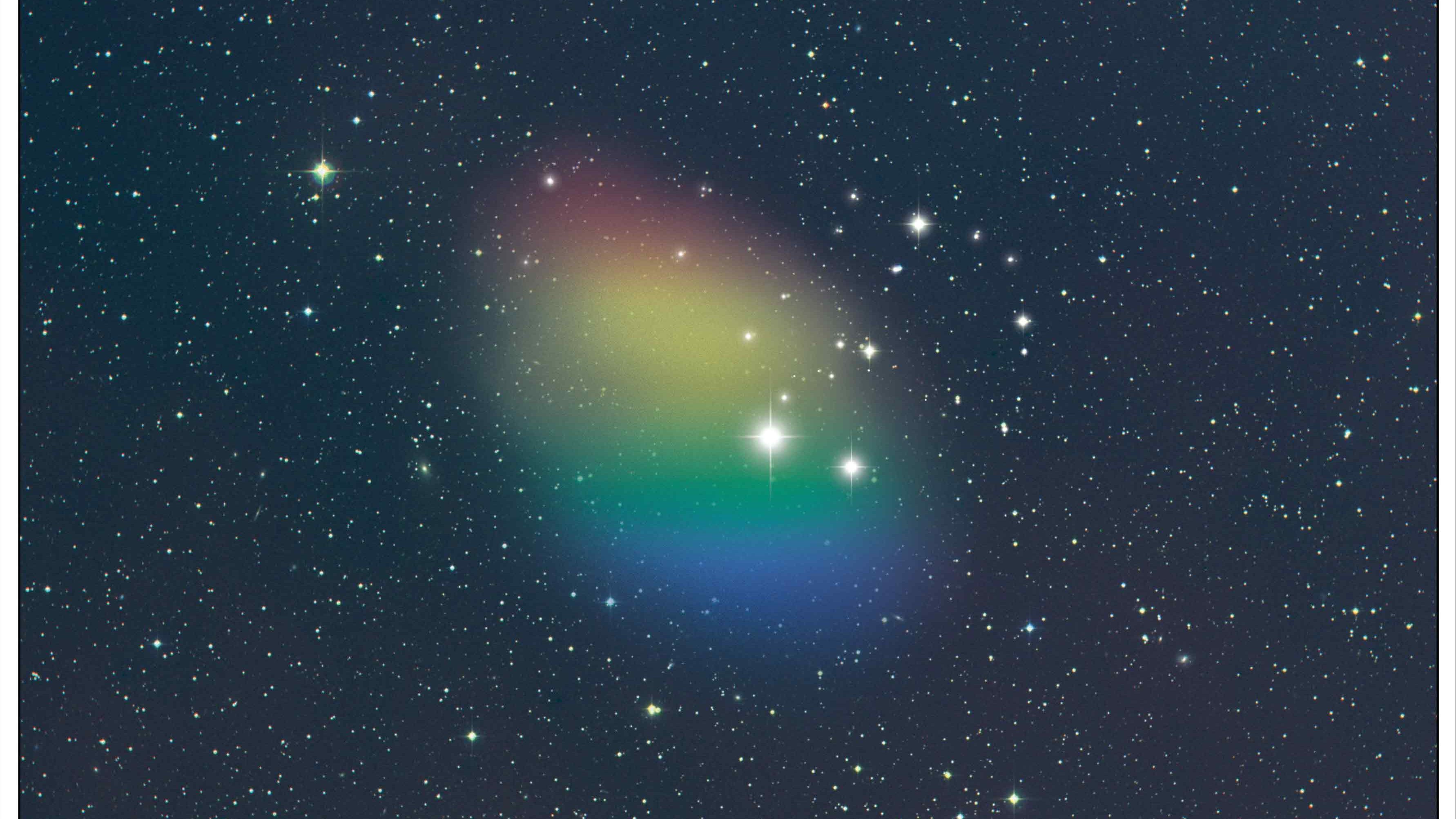

Two years ago, the Green Bank Telescope “accidentally” (because of an operator error) observed a region of sky that wasn’t supposed to have a target of interest within it, but it led to an incredible discovery. What has since become known as a dark, primordial galaxy appears to have somewhere around a billion solar masses worth of hydrogen gas in it, but no visible stars at all. However, the gas is indeed rotating and in a disk configuration, and is high enough in mass to strongly suggest that there are indeed stars within it, just below the detection limits of the tools we’ve used to observe it so far.

This star field shows a region of space with no known extragalactic sources in it, but where the Green Bank Telescope observed evidence for a large amount of neutral gas in motion, illustrated with the visible colors shown here (red/blue indicates motion away from/toward us). This might be the first dark, primordial galaxy ever discovered.

Credit: STScI POSS-II; Visualization: NSF/GBO/P.Vosteen

But Cloud 9 is an entirely different story: representing a discovery that could be our first example of a long-predicted, but never-before-observed population of astronomical objects. In theory, you fully expect that there will be systems that form with both dark matter and neutral gas, and while most of the systems with gas will collapse-and-cool to form stars, some won’t. Some, instead, will be heated up by the cosmic ultraviolet background light so that the normal matter won’t collapse, won’t form a disk, and won’t lead to the creation of stars. Instead, they might actually be reservoirs of truly pristine material: material that has not been part of the life cycle even a single star since the Big Bang.

If that’s true for this newly discovered and probed Cloud 9 system, it would be an incredibly exciting find. If there are background quasars shining through the cloud, we could perform absorption spectroscopy to detect the presence of hydrogen, helium, and nothing else. If the cosmic ultraviolet background is gradually ionizing the hydrogen within the cloud, we should be able to detect faint, diffuse emission line signatures that could reveal which elements are and aren’t present, and in what abundance. And because we already see that there’s no evidence for rotation within Cloud 9, we can conclude that this isn’t a system that’s formed a disk out of its normal matter, disfavoring any recent or ongoing star-formation episodes.

This figure illustrates the stellar masses (x-axis, logarithmically) found in stars within a galaxy versus the mass of neutral hydrogen gas (y-axis, also logarithmically) found within that same galaxy. While most SDSS galaxies follow the contours at right, and while low-mass dwarf galaxies follow the green and other-colored points at lower-right, the galaxy associated with Cloud 9 is a clear outlier, with a huge neutral gas-to-stars ratio, which is still consistent with there being no stars at all.

Credit: G. Anand et al., Astrophysical Journal Letters, 2025

Interestingly, the authors of the most recent paper about this system dutifully considered a number of plausible-sounding alternatives to this interpretation of Cloud 9.

- Could it be a foreground high-velocity gas cloud in the Milky Way? That’s disfavored by the precise match between the recessional velocity of Cloud 9 to the suspected host galaxy Messier 94.

- Could Cloud 9 instead be part of the Magellanic streams located a few hundred thousand light-years away? It’s not impossible, but the streams are located in the opposite direction of the sky to where Messier 94 is located.

- Could it be a neutral gas cloud in thermal equilibrium with the hot, ionized circumgalactic medium surrounding Messier 94? It fits many of the observed criteria, but not this one: the Universe is 13.8 billion years old, but the ongoing ram pressure interactions would destabilize the gas cloud on timescales of ~10 million years, or a factor of 1000 faster than the observed lifetime of Cloud 9.

All of this points to the REHLIC (or Reionization-Limited HI Cloud) interpretation as the leading explanation for Cloud 9. Remarkably, future observations — either longer-period observations with Hubble or superior, longer-wavelength observations with JWST — could directly probe this object to see whether the upper limit on the number of stars inside can be lowered even further, or could even be confirmed to be zero. As is so often the case in astronomy, by using different observatories sensitive to different wavelengths of light together, we can glean more comprehensive information about a system, and its nature, than even by using the newest and best observatory on its own. In astronomy, more is better, but different is also better.

Sign up for the Starts With a Bang newsletter

Travel the universe with Dr. Ethan Siegel as he answers the biggest questions of all.