The planet, roughly the size of Saturn, was detected and weighed during a rare gravitational lensing event observed from both the ground and space.

For decades, scientists have suspected that countless such “homeless” planets float through the galaxy, either ejected from their original systems or formed in complete isolation. Until now, no free-floating object of this kind had been definitively confirmed as a planet due to the difficulty of measuring both its mass and distance. That has now changed.

The study, breaks new ground by identifying the object’s mass and distance with precision, transforming rogue planets from a long-standing theory into observable reality. The researchers say their findings support the idea that the galaxy could be teeming with similar dark, starless worlds.

A Discovery Made Possible By Gravity and Luck

Detecting planets typically depends on their interactions with stars. Methods like the transit technique or radial velocity require a host star’s light or motion to reveal a planet’s presence. Without a star, a planet becomes almost invisible to telescopes, it emits little to no light and leaves no clear signal.

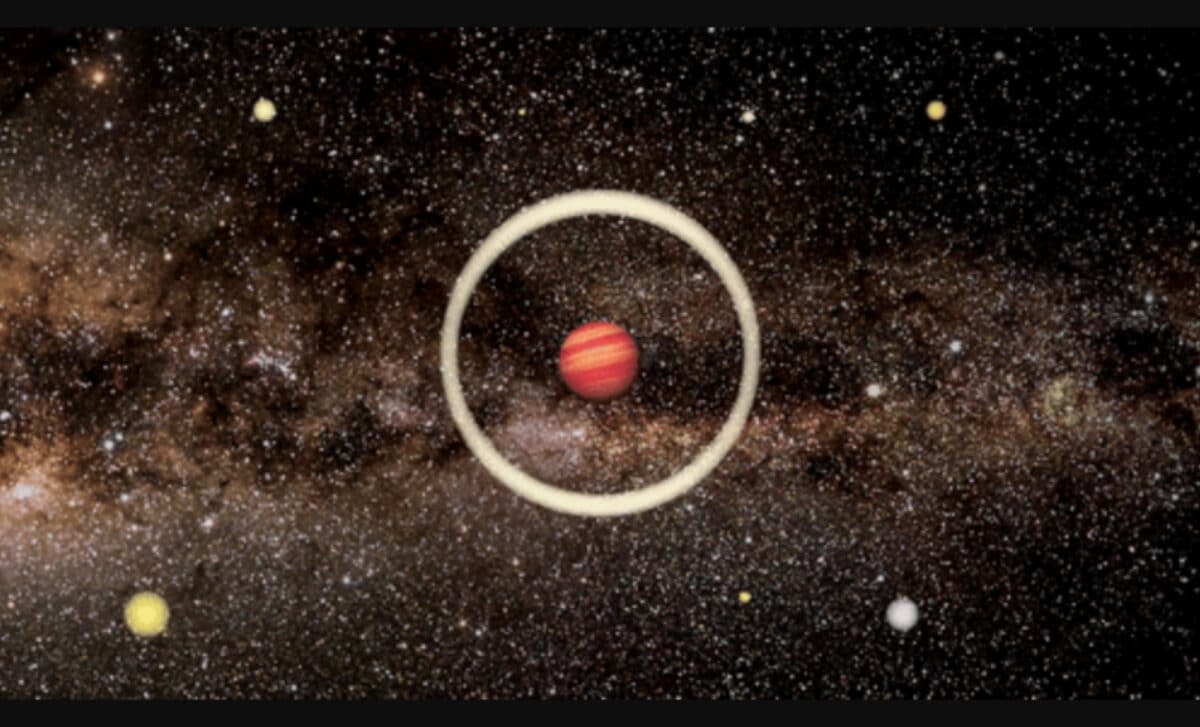

Astronomers have instead turned to gravitational microlensing to search for these elusive objects. This phenomenon occurs when a massive object, such as a planet, passes in front of a distant background star. Its gravity bends and magnifies the star’s light, briefly making it appear brighter. The brightening alerts scientists that something unseen has crossed the line of sight.

But microlensing on its own has limits. It cannot distinguish between a nearby small object and a larger one farther away. This ambiguity, known as mass–distance degeneracy, has prevented astronomers from confirming whether previously detected objects were truly planets, or more massive bodies like brown dwarfs.

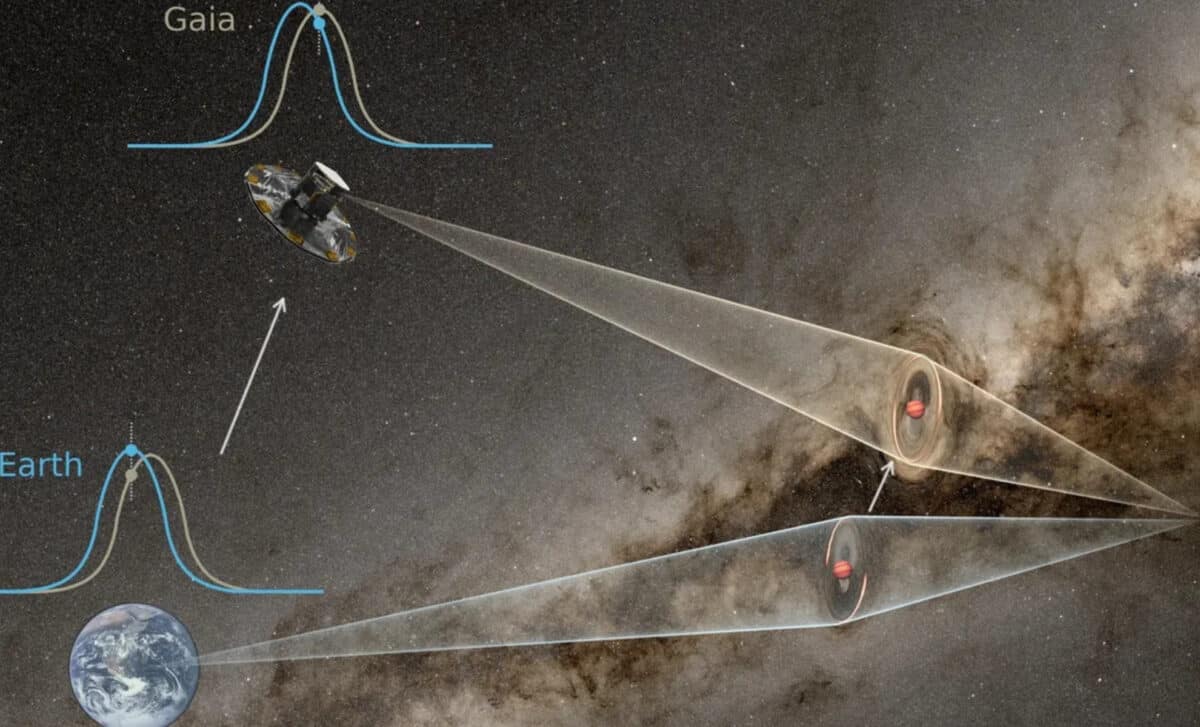

In the case of this newly confirmed object, designated KMT-2024-BLG-0792/OGLE-2024-BLG-0516, that uncertainty was resolved by a fortunate alignment. The European Space Agency’s Gaia spacecraft, which orbits far from Earth, happened to observe the same microlensing event from a different vantage point. This rare geometry caused the event to appear slightly different from space compared to the ground.

Parallax Measurement Breaks The Degeneracy Barrier

The different perspective offered by Gaia was key. Because it observed the event from a position nearly perpendicular to its precession axis, Gaia saw a slightly shifted timing of the microlensing signal. This subtle variation allowed scientists to calculate microlensing parallax—a measurement that directly reveals how far away the lensing object is.

According to the researchers, Gaia observed the event six times over a 16-hour period, beginning just before peak magnification. With that data, the team was able to accurately determine the distance of the object to be around 3,000 parsecs, or just under 10,000 light-years.

Once the distance was known, scientists could then calculate the object’s mass. The analysis showed it to be about 22 percent the mass of Jupiter, or roughly 70 times the mass of Earth, placing it just under Saturn in size.

Adding to the reliability of the measurement, the team also identified the background star involved in the event as a red giant. This detail helped refine the calculations and confirm that the object in question is neither a brown dwarf nor a stellar remnant, but a true, starless planet.

Filling A Gap In Planetary Mass Range

The mass of the newly identified planet is significant not only for confirming its planetary status, but also for where it falls on the spectrum of celestial objects. The planet lies within what researchers call the Einstein desert, a previously underpopulated range between lower-mass planets and higher-mass brown dwarfs.

Few confirmed free-floating objects had been found in this range before, raising questions about whether the gap was real or just a result of limited detection capabilities. This discovery demonstrates that the desert is not empty after all.

“Our discovery offers further evidence that the galaxy may be teeming with rogue planets,” said Subo Dong, one of the study authors and an astronomy professor at Peking University in China.

The discovery also adds weight to existing theories about the formation of rogue planets. Some are believed to have formed around stars before being ejected by gravitational forces within their systems. Others may have formed alone, never bound to a star at all.

A Step Forward, But Still Dependent On Chance

Despite the success of this detection, the technique still hinges on cosmic luck. Gravitational microlensing events are rare and unpredictable. The ability to observe one from both the ground and space, in perfect alignment, is even rarer. As a result, identifying more rogue planets with this method remains difficult.

Future missions could improve these odds. According to Interesting Engineering, upcoming observatories such as NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope and China’s Earth 2.0 mission are being designed to continuously monitor large portions of the sky. These projects could make microlensing detections much more frequent.

For now, though, this Saturn-sized planet, drifting silently through the darkness without a star, offers the strongest proof yet that lonely worlds do exist in the galaxy, and that with the right alignment, they can be revealed.