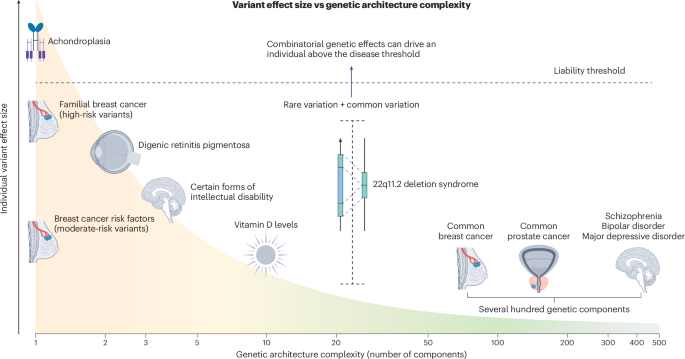

Although some genetic disorders, such as achondroplasia (related to the gene FGFR3), are caused by single genetic aberrations with near-complete penetrance, these are the exception rather than the rule. In fact, for many rare diseases, penetrance is often overestimated owing to ascertainment bias, as study samples frequently include families with probands diagnosed early or with severe disease forms, who may carry additional genetic burden. Even for highly penetrant disorders such as Huntington’s disease (HTT), the age of onset may be modified by single-nucleotide variation and background haplotypes both within and outside the HTT locus, possibly due to altered somatic stability of the CAG repeat13.

A well-characterized example of genetic modification involves breast cancer risk in women with pathogenic loss-of-function variants in the gene CHEK2. These variants approximately double breast cancer risk in women. However, this risk is further modified by polygenic background: women in the 90th percentile of a breast cancer polygenic score (PGS) reach hazard ratios (HR) of about 6, which is similar to that of carriers of pathogenic variants in the high-risk genes BRCA1/2, for whom risk-reducing surgery is recommended. Conversely, CHEK2-positive women in the lowest PGS decile have risks comparable to those in the general population14. The same modifying effect of polygenic background on monogenic risk has also been shown for familial hypercholesterolemia and Lynch syndrome (hereditary colorectal cancer). However, very different genetic backgrounds can yield the same aggregate PGS value, and the functional variants underlying many PGS signals, often tagged only by proxy markers, remain unknown. Assembling large haplotypes using lrWGS, coupled with transcriptomics and new artificial intelligence (AI)-driven sequence-to-function models that operate on large genomic regions (such as AlphaGenome15), has the potential to pinpoint the functional variants underpinning PGSs, increasing their clinical value and portability across ancestries.

A broader example can be found in NDDs, where affected individuals often present with heterogeneous clinical features. NDDs are thought to result from imbalances in intricate developmental processes that depend on the interactions of many factors, making combinatory effects from multiple gene variants more likely. Supporting this, a recent UK Biobank study demonstrated that individuals carrying multiple (2–5) deleterious variants across 599 known dominant NDD genes accounted for a significant proportion of the cognitive variability seen within these disorders3. Their findings also highlight that the variance explained by genetics increases when traits are measured on a continuous scale (for example, using fluid intelligence score) rather than by dichotomous labels such as ‘intellectual disability’. Especially for NDDs, with complex symptomatology affecting multiple cognitive domains, more comprehensive phenotypic assessments, which are likely to be substantially improved by AI-driven phenotype models16, are necessary to reveal combinatorial variant effects.

In autism spectrum disorder, a highly heritable condition characterized by a large phenotypic variability, combinatorial effects of both rare and common variant burden have been shown to significantly improve prognostic prediction models, explaining a proportion of the genotype–phenotype inconsistencies17. Additional support for the value of more comprehensive genetic profiles comes from the largest study on NDDs to date, which combined data from the Deciphering Developmental Disorders study and the Genomics England project (n = 11,573)18. The study showed that several PGSs were significantly associated with having a monogenic NDD diagnosis and, counterintuitively, that common variation burden was especially prominent in probands with affected first-degree relatives. The authors concluded that models assuming only fully penetrant monogenic causes and environmental factors can be ruled out. Mounting evidence now supports the view that the genomic context in which a high-impact coding variant resides must be taken into account if personalized medicine is to become a clinical reality.