Sometimes, when datacenter computing does a paradigm shift, things get cheaper, like the move to RISC/Unix systems in the 1990s, and then to X86 systems in the 2000s. At other times, there is an architectural shift or addition as well as a paradigm shift, and things get more expensive – at least at first. The advent of the mainframe in the mid-1960s, minicomputers in the 1970s, supercomputing in the 1980s, the Internetization of the datacenter in the 1990s, the move to cloud computing in the 2000s, and now generative AI in the 2020s.

It is funny how easy it is to find money to invest in new IT systems in both sets of examples, where things are getting more expensive as well as when they are getting cheaper. Both classes of change result in booms in spending and expansion of the IT market itself because the appetite for computing is insatiable and the desire to do new things with it is unstoppable.

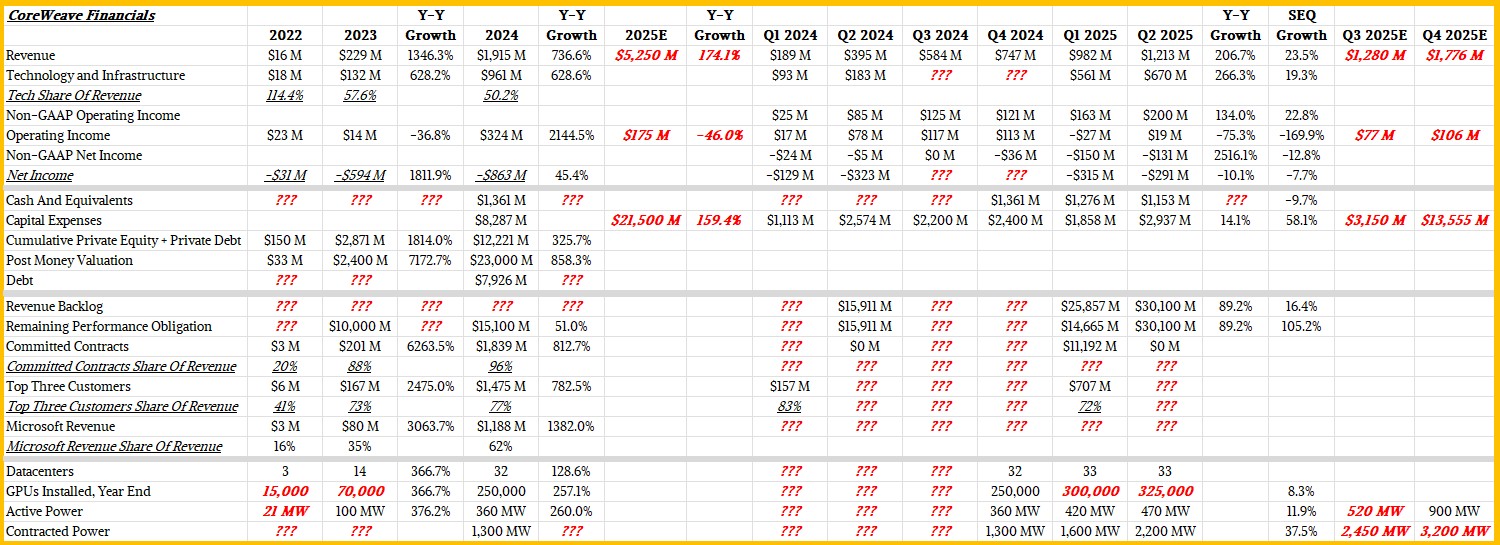

This is why the financial results of CoreWeave, which went public this year, are fascinating and illustrative. There is a new paradigm and architectural shift underway in corporate computing, and CoreWeave is lining up some of the biggest spenders in the world to make use of infrastructure as fast as it can build it. And it is building it as fast as it can scrounge up the money and as fast as XPU makers can deliver their compute engines.

Before we get into the Q2 2025 financials for CoreWeave, let’s have some fun with ratios for both Amazon Web Services, the champion of the cloud era and also a huge player in AI processing, and this neocloud upstart based in New Jersey.

We have data going back to Q1 2008 on Amazon’s capital spending, which covers its retail warehouses and transportation systems as well as the datacenters and IT infrastructure for its AWS cloud unit, which is two years after AWS was launched and when Amazon’s capital spending took off and when AWS revenue became material enough to start hinting about it. In our model, we reckon that AWS represented about 40 percent of capital spending in early 2008. This is important because the ratio we are interested in is revenue divided by capital expenses.

At the time AWS was started, Amazon was looking for a way to provide utility computing to make money sufficient to cover the costs of its own substantial IT investments as well as to create a new, highly profitable service that would shake up the transactional IT market of companies buying machines and trying to make the most of them over five to ten years. To say that it has been wildly successful is an understatement. In the trailing twelve months, AWS has brought in $116.4 billion in revenues and 36.8 percent of that – $42.8 billion – is dropping to the middle line as operating income. AWS is a larger IT supplier than any of the historical OEMs in the world, and at the moment in the IT sector only Nvidia, one of the key parts suppliers to AWS, rakes in more money than AWS from the datacenter sector.

Way back in 2008 and early 2009, the average ratio of revenue to capex was 0.7 to 1 for AWS, but as the use of S3 storage and then EC2 compute on the cloud grew, it quickly rose to an average 0.9 to 1 until the end of 2011. At that time, revenue started growing faster than capex spending, and the ratio averaged around 1.7 to 1 up through the end of 2022 when the GenAI boom started. The ratio wiggled around some in those eleven years, from 1.0 to 2.7 depending on where AWS and its suppliers were at in their upgrade cycles and where AWS was at in its ever-decreasing pricing for compute and storage, but it did cluster around 1.7 fairly tightly. (It is probably better to look at these numbers annually, but we are just trying to make a point here.)

There was a cooling of IT spending in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic abating (after a huge burst as it got roaring in 2020), but with the GenAI boom, has doubled in the past five quarters, and it looks like the vast majority of that spending is for AI clusters. And guess what? The ratio of AWS revenue to IT capex is around 1.9 to 1.

Said another way, in the GenAI world, if you want to make $2 in the current quarter, then you had better have been spending 50 cents in some quarter X months ago and you better be spending $1 now so you can make $4 in a future where you will be spending $2 to cover future AI hardware needs even further down the road.

So where is CoreWeave at in this journey of IT spending and revenues? It is just beginning, although admittedly we do not have as much data to work with because CoreWeave is so young and its financials do not span a large amount of time. Take a look:

In 2024, CoreWeave had $1.92 billion in sales and had capital expenses of $8.29 billion, which gives a ratio of 0.23 to 1. Basically, the neocloud is spending four times as much today to cover future revenue generation as it is making today. And if you take the midpoint of its revenue expectations for the third quarter and the full 2025 year and do the same for capital expenses, the ratio works out to 0.24 to 1. This is clearly a massive buildout phase for CoreWeave, not the least of which because it has secured $15.9 billion in GPU capacity rentals from OpenAI and has two hyperscalers (one presumably Microsoft, and possibly to meet its obligations to OpenAI, and the other is possibly Google, which also has obligations to OpenAI) that have also signed contracts.

Given the demand for AI processing, it make some time for revenues and capital expenses to balance out, and even longer for revenues to start growing faster than capital expenses. But clearly, eventually that revenue has to be a lot bigger than spending for CoreWeave to build a sustainable business and the capex has to slow down so it can be rented and amortized in a way that makes the company some profits. This will eventually happen, but it is far more likely that with CoreWeave, OpenAI will get the neocloud the money it needs to invest in the hottest technology and get first dibs on using it, and then over time, older technology will be adopted by others to do their training and inference. This, if anywhere, is where the profit will come from, we think.

In the quarter ended in June, CoreWeave had $1.21 billion in sales, and a non-GAAP operating income of $199.8 million. But real operating income was only $19 million, and the company had a net loss of $290.5 million. CoreWeave spent $2.94 billion on capital expenses in Q2, which was 14.1 percent higher than a year ago and up 58.1 percent sequentially from the $1.86 billion it spent in Q1.

In the company’s forecast for the third quarter, it said that revenues would be between $1.26 billion and $1.30 billion, and if we work backwards from the annual forecast for 2025 (more on that in a minute), then at the midpoint of the range for the full year and given two quarters done, then operating income should be around $77 million. Capital spending in Q3 – based on the two quarters under the belt and the annual forecast once again – should be $3.15 billion at the midpoint.

The top brass at CoreWeave told Wall Street to expect annual revenues between $5.15 billion and $5.35 billion for the full 2025 year, with operating income of between $160 million and $190 million and with capital expenses of between $20 billion and $23 billion. That is another way of saying that Q4 will have a whopping $13.6 billion in capex against maybe $1.78 billion in revenues, but an operating income of maybe $106 million, give or take. While no one has talked about it, all of this spending is for datacenters and systems based on Nvidia “Blackwell” GPUs, we think.

That is not to say that older infrastructure based on “Ampere” A100 and “Hopper” H100 GPUs from Nvidia is not being used, and that CoreWeave doesn’t have some on-demand customers filling in the gaps between companies with large contracts as OpenAI has.

“The overwhelming majority of our infrastructure has been sold in long-term structured contracts in order to be able to deliver compute to our clients that need to consume it for training and for inference over time,” Michael Intrator, CoreWeave’s co-founder and chief executive officer, said on the Wall Street call. “And so, we don’t see a real fluctuation in the economics associated with inference or training. Having said that, I think that it stands to reason to think that when a new model is released and there is a rush to explore the new model, to use the new model, to kind of drive new queries into it, you will see a spike in demand within a given AI lab that may cause there to be a spike in the short-term pricing associated with inference. And we see those. But as we said before, the on-demand component of compute is a very small percentage of our overall workloads. And we are observing inference cases on older generations of hardware – the A100s, the H100s. They are still being re-contracted out. They’re being bought on term in order to serve the inference loads that people continue to have, continue to see and need compute to be able to serve.”

Here is how a CoreWeave deal works:

It takes plenty of cash on hand to do these deals. Customers do an initial prepayment, which keeps the coffers full at CoreWeave, which turns around and buys GPUs and other infrastructure as part of the deal. When this is delivered, CoreWeave pays for it, and it takes about three months to install the stuff in what is called a “power shell datacenter,” a kind of modular and repeatable design that also allows some customization but which can be deployed relatively quickly. The AI systems are up and running around month six and the monthly payments for capacity usage start; the initial payment is tacked on the end and pays down the contractual capacity that was acquired by the user.

As Q2 was coming to an end, CoreWeave had a backlog of $30.1 billion in capacity that was on the books, which was up $4.2 billion compared to Q1 and nearly double that from last year. The company ended Q2 with 470 MW of active capacity, up 11.9 percent from Q1, with contracted power of 2,200 MW, up 37.5 percent from the 1,600 MW in Q1. With all of that infrastructure going in during Q4 2025 (and we think well into Q1 2026), CoreWeave says it will have another 900 MW of activate capacity by the end of this year. We estimate that another 50 MW comes in Q3 with the remaining 380 MW coming in Q4. And once the $9 billion all-stock acquisition of rival and partner Core Scientific is completed by the end of the year, there will be another 1,300 MW of active capacity. By the end of the year, the combined CoreWeave-Core Scientific will have 2,200 MW of active capacity, and that means contracted capacity will have to grow. Our best guess is to at least 3,200 MW to get the ratio of contracted to active capacity back down to 3.6 to 1 or so as it was in 2024 and Q1 2025.

It will be funny if damned near all of the capacity that CoreWeave has installed is for OpenAI (including flow-through deals with Microsoft and Google, who have their own partnerships with OpenAI for capacity) and that the vast majority of its revenues really come from OpenAI. The company did not discuss this in the call with Wall Street, which seems to be something that is material as far as we are concerned.

Featuring highlights, analysis, and stories from the week directly from us to your inbox with nothing in between.

Subscribe now

Related Articles