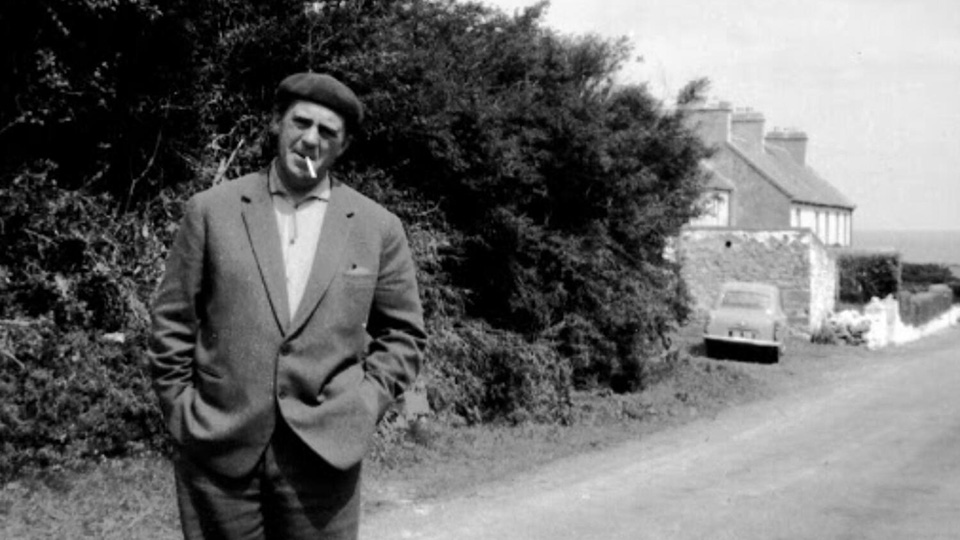

July marked the fortieth anniversary of the death of the German writer, Heinrich Böll (1917-1985). However, it was in August that I finally managed to make my own pilgrimage to the house he called home in Achill Island, in Dumha Goirt. There I am, finally, my wife taking my picture, and me as giddy as an Elvis fan outside of Graceland.

The house is still in use as an artist’s residence and an annual summer school is held in Böll’s honour on the island. Many of those talks are to be found on YouTube. Of course, it is impossible for any Irish speaker not to take an interest in the placename. Ó Dónaill translates “gort” as meaning both “field of agriculture, ‘gort arbhair’, field of corn, ‘gort féir’, field of grass” and “battle-field; ‘gort gaisce’, field of valour”. Dumha is even more fascinating: mound, tumulus; ‘dumha seilge’, hunting mound, look-out place for leader of the hunt; ‘dumha sí’, fairy mound; ‘dumha na marbh’, grave-mound.

Throw that all into the place where Boll lived for decades, a field where things grow and fight and a mound from which to hunt and remember the dead and, of course, the sí, the unseen inhabitants of Ireland, na daoine beaga, who have haunted the Irish for millennia, whispering in the night.

In truth though, I imagine Böll with the harvest and the beginning of a new school year, Meán Fómhair, more than the Summer because, in the early 1980s, a couple of years before his death, I read Böll for the first time as a student in secondary school. That book, Doktor Murkes gesammeltes Schweigen, is still on the shelf, with its stories of war, loss and love.

Many of the stories were hard going for a learner; there are passages that are as dense as a summer hedge row: verbs; nouns and adjectives tightly wrapped around one another. There were moments of fun, though. One of the stories in the collection is called Die Waage der Baleks. “What story are we starting this week, boys?” “The Scales of the Bollix, sir,” says my classmate, J. We laughed. Who says learning languages, learning German in particular, cannot be fun? And look, wasn’t it a clever pun for someone in their late teens, from Belfast, to make? Languages!

I claim no encyclopaedic knowledge of Böll, his life or works. I have read many of his books, mostly in English, and know him as a reader, someone whose work I value and have sought out over the years. Like many who have learnt a language unsuccessfully, I cling to the little I know but which I value nonetheless. There are many lines, phrases, paragraphs, that are still within the grasp of my very poor German, my other school language: “Ich bin bereit, den Rhein alles zu glauben…” “I am prepared to believe everything about the Rhine…”

I visited Böll in Germany, without realising it, before I got as far as Achill. There was a school trip to Cologne, his home city. We visited the invasion beaches of Normandy on the way too where the German pill boxes still stood but were full of graffiti of a more contemporary kind. One of the school staff with us, an American by birth, had been in the USAAF during the war. He had been based on England’s airbases and serviced the B-17s that, ironically enough, bombed Cologne, amongst other German cities. I was too young to talk with him about such things but I wonder what he felt as he traced his way with us, gurning, on a long bus trip through England, a channel ferry, Normandy, Belgium and then into the Rhineland.

In the small town where we stayed, I bought a wooden crucifix which is still on the wall of my parent’s home in Belfast, a small reminder, and tie, to a different land but one with which we poor unloved Nordie nationalists shared a common religion. Odd the connections we make in life, the things we place in our home and memories.

Eine Grenze

Damals in Odessa (Once upon a time in Odessa) is another story that still lingers in my ken. This is one about Wehrmacht soldiers in Odessa during the Second World War and, growing up in Belfast, there were soldiers then too, in Andytown: “Damals in Odessa war es sehr kalt.”/“At that time in Odessa it was very cold.”

(Do not ask me to translate the second sentence; there are over 70 words in that alone and it sparks with all the lovely German grammar you could hope for: masculine, feminine and neuter nouns wrestling with each other through the nominative, accusative and dative, singular and plural. It is as thick as treacle.)

Böll served on the Eastern and Western Fronts and I imagine that he would have recognised many of the place names from that era popping up in the headlines of this more recent conflict between Russia and Ukraine. Still, soldiers are soldiers and foreign climes are foreign climes, whether it be the conscripted Wehrmacht soldier in Eastern Europe or the Brummie squaddie in West Belfast. The fear of dying, I suspect, was much the same.

(Of course, Böll was also part of the school curriculum that included the poetry of Wilfred Owen and O’Casey’s Juno and the Paycock: “Boyle, no man can do enough for Ireland.” What were the Christian Brothers thinking making us read this stuff?)

Böll’s Irisches Tagebuch is undoubtedly one of his best known works among Irish readers. It details his journey to Achill back when – damals! – Ireland had those “bad roads” about which John Waters has written so eloquently. Lines of that still stand out in the mind, so still are they in their distillation: „Als ich an Bord des Dampfers ging, sah ich, hörte und roch ich, daß ich eine Grenze überschritten hatte … aber hier auf dem Dampfer war England zu Ende; hier roch es schon nach Torf… ” (“When I went on board the steamer, I saw, heard and smelt that I had crossed a border … here on the steamer England had come to an end; here it already smelt of turf…”)

An Ghaeltacht

That book is on the shelf in German, in English and also in Irish, as Dialann as Éirinn, which seems more than appropriate as Böll’s cottage is, in fact, in the Gaeltacht.

(There is a pub question for you now: “Name the Gaeltacht-based writer who won the Nobel Prize for Literature?”)

Heading to Achill the visitor soon sees the very physical border marked “An Ghaeltacht”, the demarcation line, and prayer, between hope and reality. Did I hear anyone speaking Irish while in Achill? No, I didn’t but it was a short trip and the little café where I had a coffee did boast that the staff spoke Irish. Alas, I have gotten to that age when I am frightened to speak Irish in the Gaeltacht unless I know the person does, in fact, speak Irish. Needless to say, much of the island signage was in Irish, which lifts the mood and, as I say to those who visit the Gaeltacht, the sign “An Ghaeltacht” is a bit like marking out “The Atlantic”; there will be whales out there but you just might not see them.

Odd too how we learners of languages make connections in our minds. The Rhine is a masculine noun in German and Gaeltacht a feminine one in Irish, a suitable marriage for a writer. Is that too much, too florid an observation, a stretch in this sub-par piece in the style of Sebald? Perhaps it is, but still masculine and feminine place names, old gods of Germany, meeting old gods in Ireland, ancient languages warping under the weight of contemporary life, seeping into the imagination, whispering away through Europe.

There is something magical in the thought that this master of world literature found sanctuary in the Gaeltacht, that he wrote in a language other than English, which is no small thing. (An Ghearmtacht?)

Still, is it too hysterical to suggest that German is becoming as redundant as Irish in these days of ever-quickening English; that even the German language is beginning to buckle under the weight of English? Many a YouTube video of younger German speakers will have loan words from English – not unlike Gaeltacht Irish. The precise German grammar that was drummed into me seems to be fracturing too. The genitive, to this ignorant ear, is being pushed aside by the dative dalba. „Das Haus des Mannes” is beginning to become „Das Haus von dem Mann”. That is sort of German that lost me marks a lifetime ago. (Again, not unlike Irish.)

These things matter. English wounds all languages, it seems, their grammar, essence and being – even those which have traditionally been European powerhouses. That old taunt of our own ignorant, native philistines, “What use is Irish?” is one that could be directed too at German, French, Italian. After all, the whole world speaks American now.

That is certainly not to suggest that there are not writers of value or importance still ploughing their little furrow auf Deutsch. The philosopher Byung-Chul Han is from South Korea but writes in German. A Catholic from a partitioned country – Böll would have recognised that – he has quietly won himself a reputation as being one of the world’s leading thinkers on contemporary life and its mores.

I read him in English but some of his books or, more correctly, the translations, are sprinkled with words in German, little clues to let you know – is leor nod don eolach – that the text you are reading is not entirely the text that was written, that there is a language behind the language, that you might need to feel the warm breath of ruach to be fully informed of that which is on the page. They function as a reminder of the mystery of languages, of the impossibility at times of rendering the being of a word or expression, in one language, into bald English.

I read Böll and Máirtín Ó Direáin at the same time at school, learning one language well and the other not so much. Both languages have informed and inspired my reading and reflection over many decades. I could not but help recall Ó Direáin while standing at Böll’s cottage: “Thóg an fear seo teach…” “This man built a house…” “A choinnigh a chuimhne buan” “Which kept his memory alive”.

Yes, that will do. Haus. House. Teach. Gaeltacht. Teanga. Sprache. Der Rhein. An Ghaeltacht. Damals. Fadó. Leabhar agus Buch. Torf.