Sign up for the Starts With a Bang newsletter

Travel the universe with Dr. Ethan Siegel as he answers the biggest questions of all.

Although the Universe constantly evolves, astronomers rarely see that evolution.

This snippet from a structure-formation simulation, with the expansion of the Universe scaled out, represents billions of years of gravitational growth in a dark matter-rich Universe. Over time, overdense clumps of matter grow richer and more massive, growing into galaxies, groups, and clusters of galaxies, while the less dense regions than average preferentially give up their matter to the denser surrounding areas. The “void” regions between the bound structures continue to expand, but the structures themselves, once they become bound in any fashion, do not.

Credit: Ralf Kaehler and Tom Abel (KIPAC)/Oliver Hahn

Instead, we get snapshots: stars and galaxies that barely change over human timescales.

Imaged here in 9 different wavelength filters (from 0.9 to 4.8 microns) for a total of 120 hours, this JWST view of Abell S1063 is one of the most massive clusters ever imaged with deep field techniques. Many gravitationally lensed features can be clearly seen even with the naked eye. These objects are so large and distant that even observations decades or centuries apart would show no practically discernible difference.

Credit: ESA/Webb, NASA & CSA, H. Atek, M. Zamani (ESA/Webb); Acknowledgement: R. Endsley

Nearby transients, however, like stellar explosions and cataclysms, provide an exception.

The brightening and dimming novae, along with bright stars, as imaged by XMM-Newton and Chandra at the center of the Andromeda Galaxy. These novae are consistent with an extremely large distance of a million light-years or more for the Andromeda galaxy, but inconsistent with these novae occurring within our own Milky Way.

Credit: Max-Planck-Gesellschaft, data from 2003-2016

Because they change rapidly, evolution often appears on timescales of years or decades.

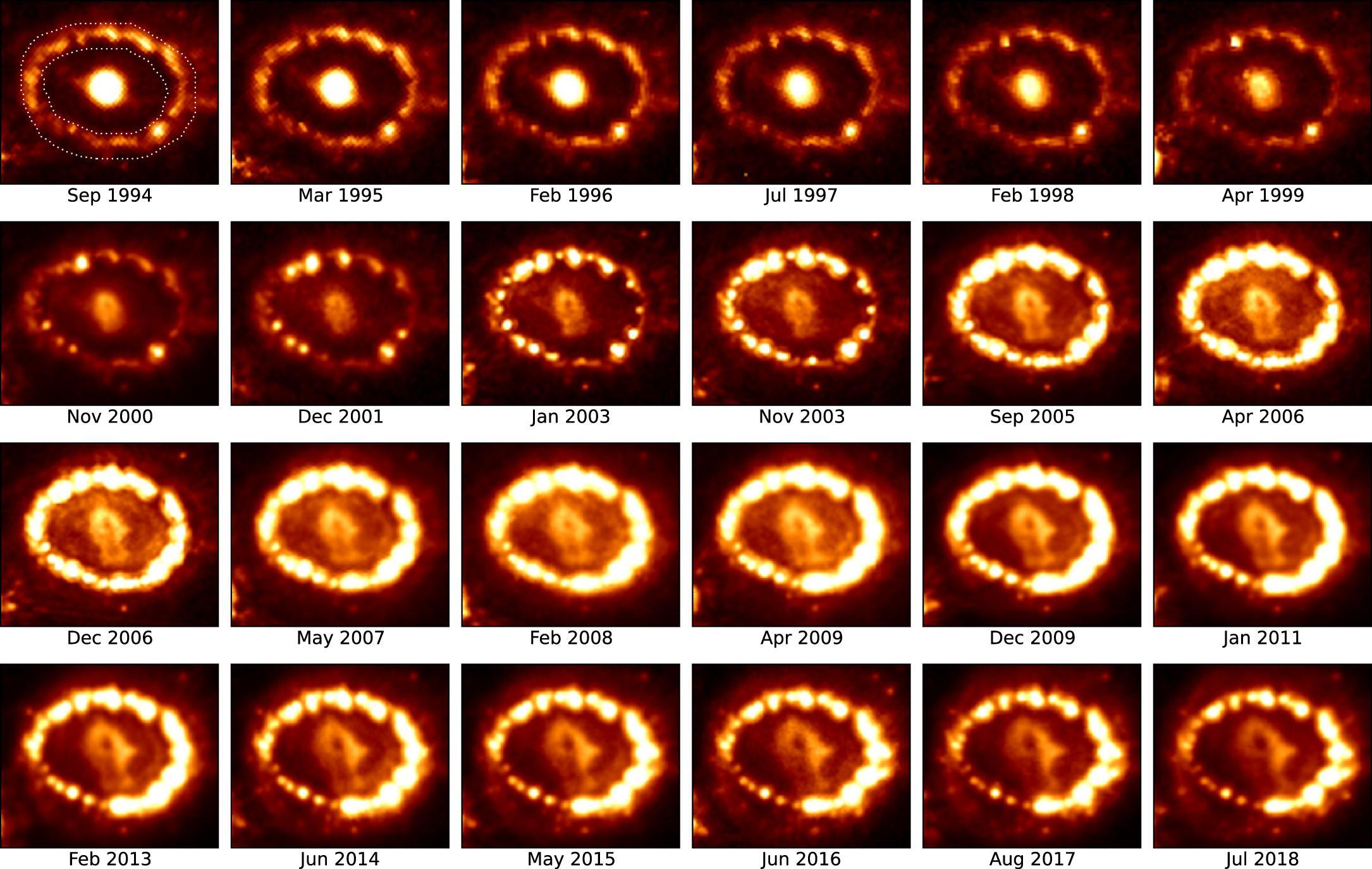

The outward-moving shockwave of material from the 1987 explosion continues to collide with previous ejecta from the formerly massive star, heating and illuminating the material when collisions occur. A wide variety of observatories continue to image the supernova remnant today, tracking its evolution. However, the innermost region remains heavily dust-obscured, preventing us from truly knowing what’s going on inside.

Credit: J. Larsson et al., ApJ, 2019

With NASA’s Chandra lasting more than 25 years, recent supernovae changes are apparent.

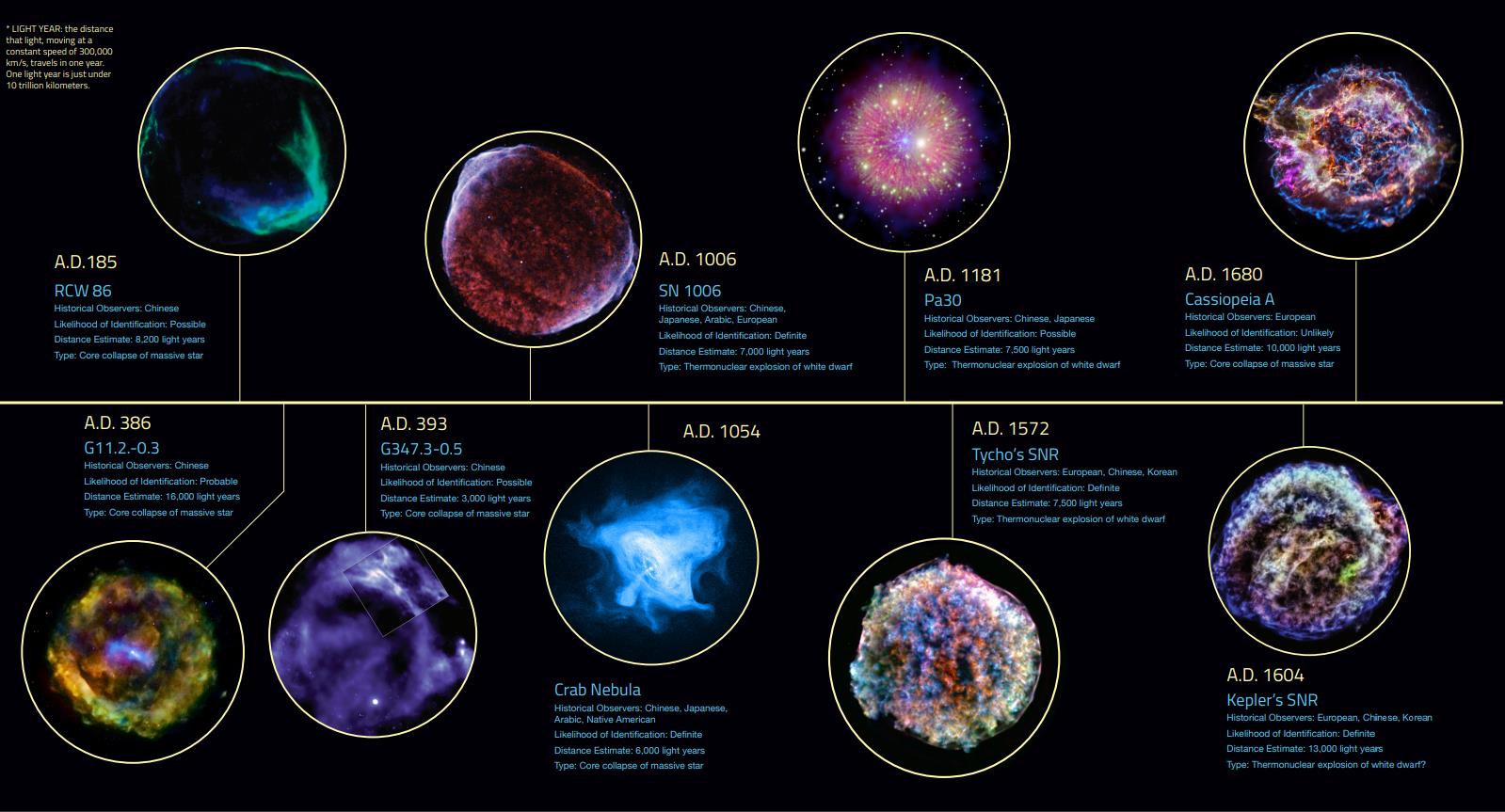

This infographic shows nine of the ten historical supernovae, along with remnants, that have been identified over the past 2000 years within the Milky Way. Not shown is G1.9+0.3, which occurred near the galactic center approximately 155 years ago, but was only discovered posthumously in 1985. Our best supernova remnant observations all come from NASA’s Chandra X-ray telescope.

Credit: NASA/Chandra X-ray telescope

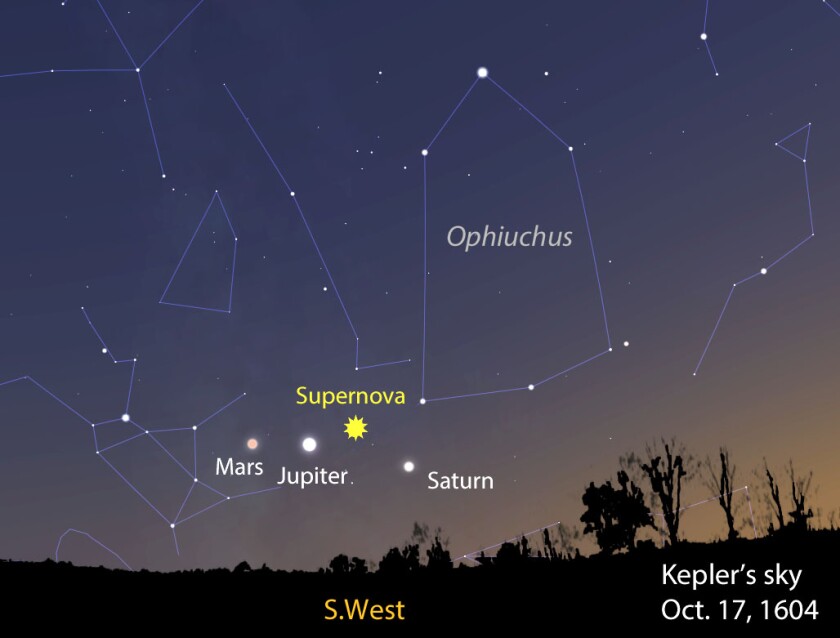

Our galaxy’s last naked-eye supernova was Kepler’s supernova, appearing back in 1604.

In 1604, a supernova appeared to skywatchers on Earth, between the constellations of Ophiuchus and Sagittarius. Known as Kepler’s supernova, on October 17, 1604, it made a brilliant “line” with Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn flanking it.

Credit: Sterllarium/InForum

This type Ia supernova arose from an exploding white dwarf 17,000 light-years away.

This animation of the double detonation scenario shows two white dwarfs in close orbit around one another. When material accumulates onto one member, it can cause a surface thermonuclear reaction, which can then propagate around the star until it triggers a core detonation. This scenario could be responsible for up to 100% of observed type Ia supernovae.

Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center Conceptual Image Lab/Adriana Manrique Gutierrez (USRA)

After brightening and then fading away, the supernova remnant was discovered in the 20th century.

This Hubble Space Telescope image shows the visible light afterglow of Kepler’s supernova remnant from back in 1604. The remnant of an exploded white dwarf, there’s very little in terms of an optical afterglow signature, but it’s still present, and was only discovered more than 300 years after the supernova went off: in 1941, by Walter Baade.

Credit: NASA/ESA/R. Sankrit and W. Blair (Johns Hopkins University)

Then, in 2000, NASA’s Chandra X-ray observatory began surveying it.

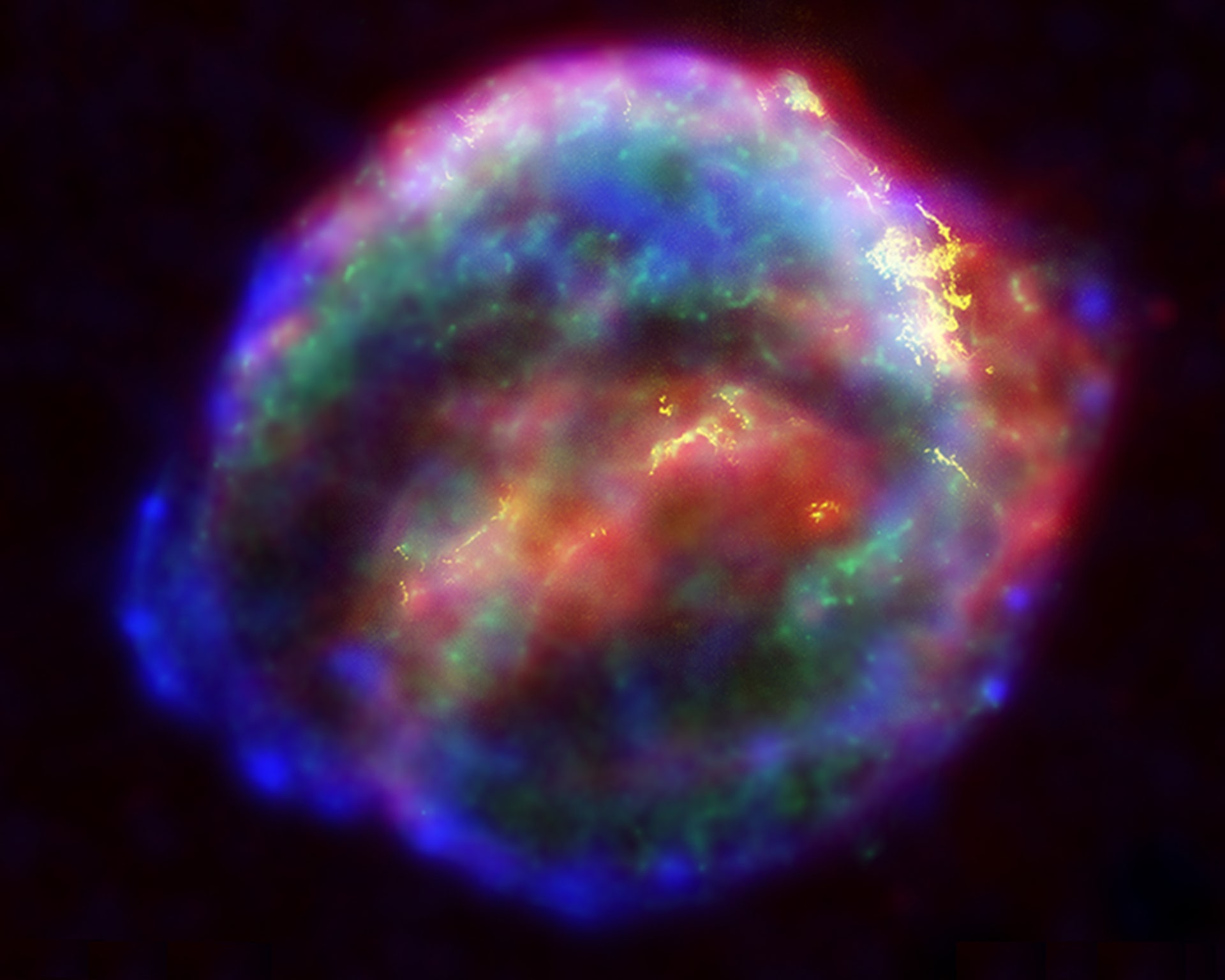

In 1604, the last naked-eye supernova to occur in the Milky Way galaxy happened, known today as Kepler’s supernova. Although the supernova faded from naked-eye view by 1605, its remnant remains visible today, as shown here in an X-ray/optical/infrared composite. The bright yellow “streaks” are the only component still visible in the optical, more than 400 years later.

Credit: NASA, R. Sankrit (NASA Ames) and W.P. Blair (Johns Hopkins Univ.)

It revealed many features, including a circular — but asymmetric — blast wave.

This multi-energy X-ray observation of Kepler’s supernova remnantfrom 1604, taken 402 years later in 2006, shows the debris from the long-ago exploded star in X-ray energies. The different colors represent characteristic signatures of a variety of chemical elements, showing differentiation and asymmetries within this supernova remnant.

Credit: NASA/CXC/NCSU/S.Reynolds et al.

Chandra returned to view it repeatedly: in 2004, 2006, 2014, and 2025.

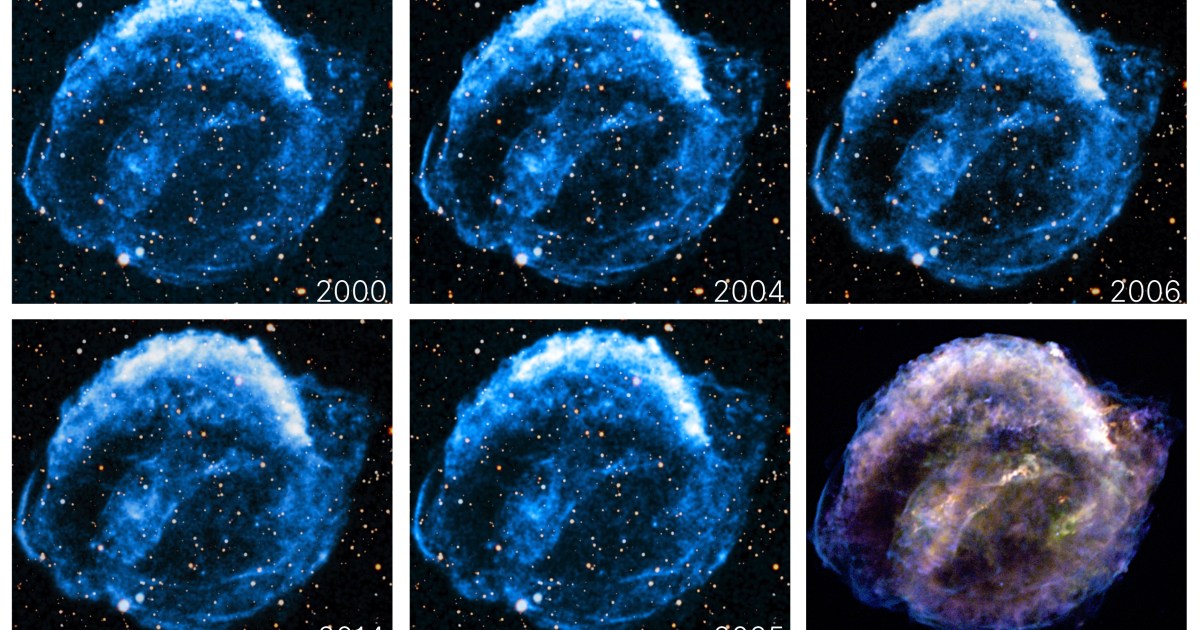

The entirety of the supernova remnant from Kepler’s supernova of 1604 can be seen expanding over a 25 year baseline thanks to periodic X-ray observations from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory. This 25 year observation baseline represents 6% of the total age of the supernova remnant.

Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/SAO; Optical: Pan-STARRS; GIF animation: E. Siegel

This 25 year observational baseline represents 6% of the supernova remnant’s cumulative age.

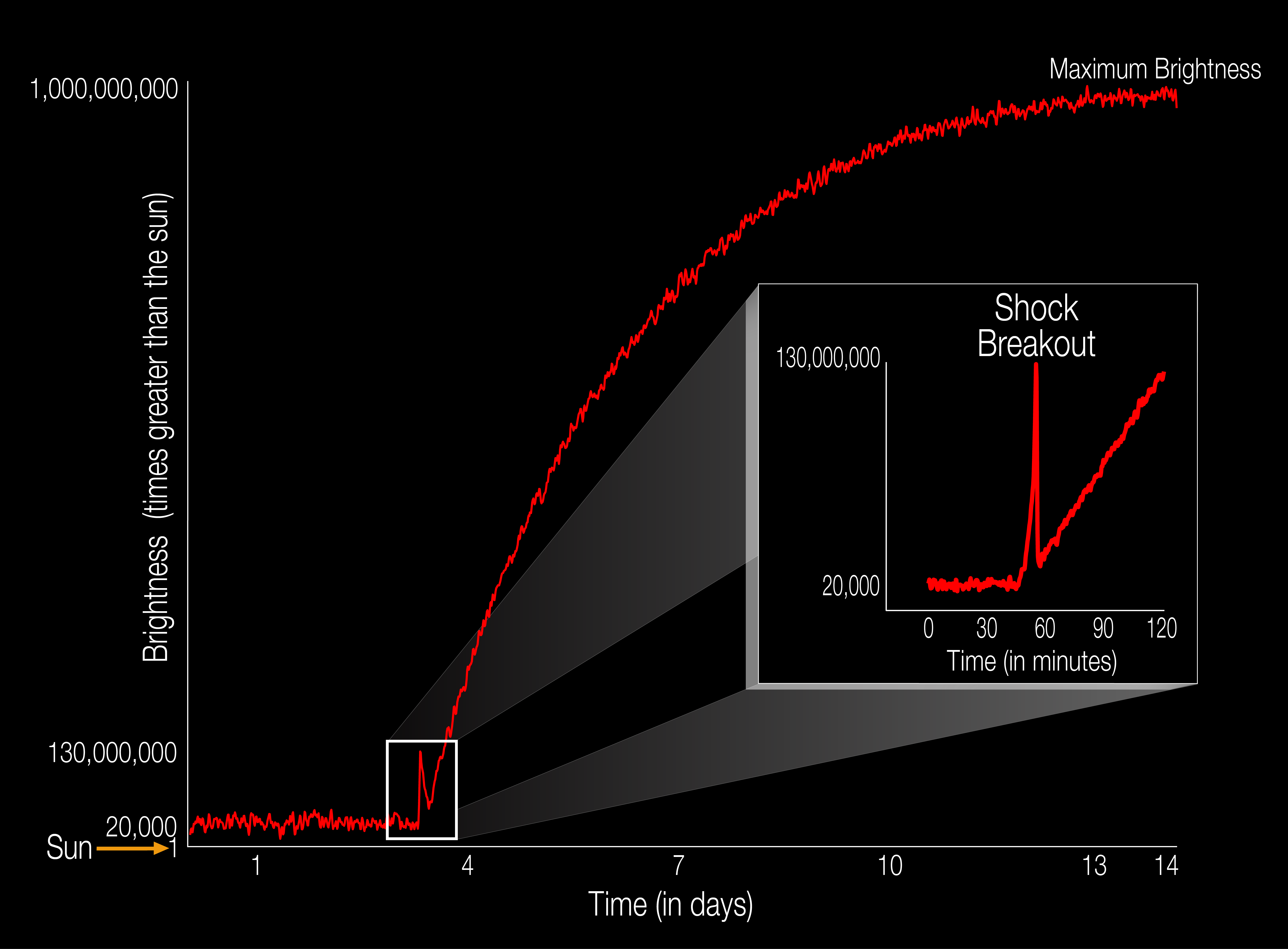

In 2011, one of the stars in a distant galaxy that happened to be in the field of view of NASA’s Kepler mission spontaneously and serendipitously went supernova. This marked the first time that a supernova was caught occurring in the act of transitioning from a normal star to a supernova event, with a surprising ‘breakout’ temporarily increasing the star’s brightness by a factor of about 7,000 over its previous value. Observations such as these were impossible in 1604, but may be possible for the next naked-eye Milky Way supernova.

Credit: NASA Ames/W. Stenzel

The supernova’s shockwave expanded by 0.5 light-years over that time: roughly 2% the speed of light.

Relative to our point of view, the background stars lying in the same field-of-view as the remnant of SN 1604 appear not to move at all, while the supernova blast wave expands rapidly with respect to them. At its distance of 17,000 light-years, this animation shows the fastest portion of the expansion: at 14 million miles per hour, or 6200 km/s (just over 2% the speed of light).

Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/SAO; Optical: Pan-STARRS; GIF animation: E. Siegel

The northern expansion is slowest, at 1800 km/s, with southern expansion the fastest, reaching 6200 km/s.

This zoomed-in portion of Kepler’s supernova remnant as imaged with NASA’s Chandra X-ray telescope shows how the blast wave has expanded in the slowest section: at about 4 million miles per hour, or around 1800 km/s: around 0.6% the speed of light. The slowest expansion corresponds to the highest density of material in the interstellar medium.

Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/SAO; Optical: Pan-STARRS; GIF animation: E. Siegel

Faster speeds require lower-density mediums, implying an asymmetric surrounding environment.

This zoomed-in version of the 25-year timelapse of the expansion of Kepler’s supernova remnant from 1604 allows us to see the asymmetric nature of the blast wave and the expansion in great detail, where the thickness of the speed of the blast wave is dependent on the density of the surrounding interstellar medium.

Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/SAO; Optical: Pan-STARRS; GIF animation: E. Siegel

The blast wave’s width is also measurable, showcasing Chandra’s prodigious, enduring capabilities.

Mostly Mute Monday tells an astronomical story in images, visuals, and no more than 200 words.

Sign up for the Starts With a Bang newsletter

Travel the universe with Dr. Ethan Siegel as he answers the biggest questions of all.