The joint NOvA-T2K analysis combined years of data to measure a neutrino mass difference with less than 2% uncertainty.

Teams in Japan and the United States merged results from the NOvA and T2K experiments, bringing two neutrino beams into one fit.

The work was co-led by Ryan Patterson, Ph.D., at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in Pasadena.

Patterson builds tools to track neutrino identity changes and to test whether matter behaves differently from antimatter.

By pulling together observations from two separate beamlines, the analysis reduces blind spots that any single detector leaves.

Why neutrinos matter

The analysis matters because neutrinos are central to laws that shape stars, elements, and cosmic history.

Trillions pass through a person each second, and the weak interaction, a force that makes direct detections rare, leaves little trace.

Could neutrinos help explain why matter outlasted antimatter after the Big Bang, leaving stars and people behind?

This section of the analysis tracks how neutrinos switch among three identities during flight through Earth.

Physicists call each identity a flavor, a label tied to the charged particle produced in a hit.

A neutrino flavor is a mixture of three mass states, and mass ordering, which mass state is lightest, affects oscillation patterns.

How oscillations work

The analysis relies on neutrino oscillation, flavors changing as neutrinos travel, which proves neutrinos have mass.

Oscillation happens because the mass states move with slightly different rhythms, so the mixture at arrival is changed.

Passage through rock adds the matter effect, electrons in Earth nudging oscillations, which helps separate ordering from other parameters.

Two beams, one goal

Using two long-baseline beams sent hundreds of miles through rock, the analysis compares experiments that track neutrino changes.

NOvA sends neutrinos about 500 miles (810 km) from an accelerator near Chicago to a detector in Minnesota.

T2K launches a beam about 185 miles (295 km) from Tokai to the Super-Kamiokande detector in Kamioka.

Detecting rare hits

To succeed, the analysis depends on spotting the few neutrinos that finally interact inside huge detectors.

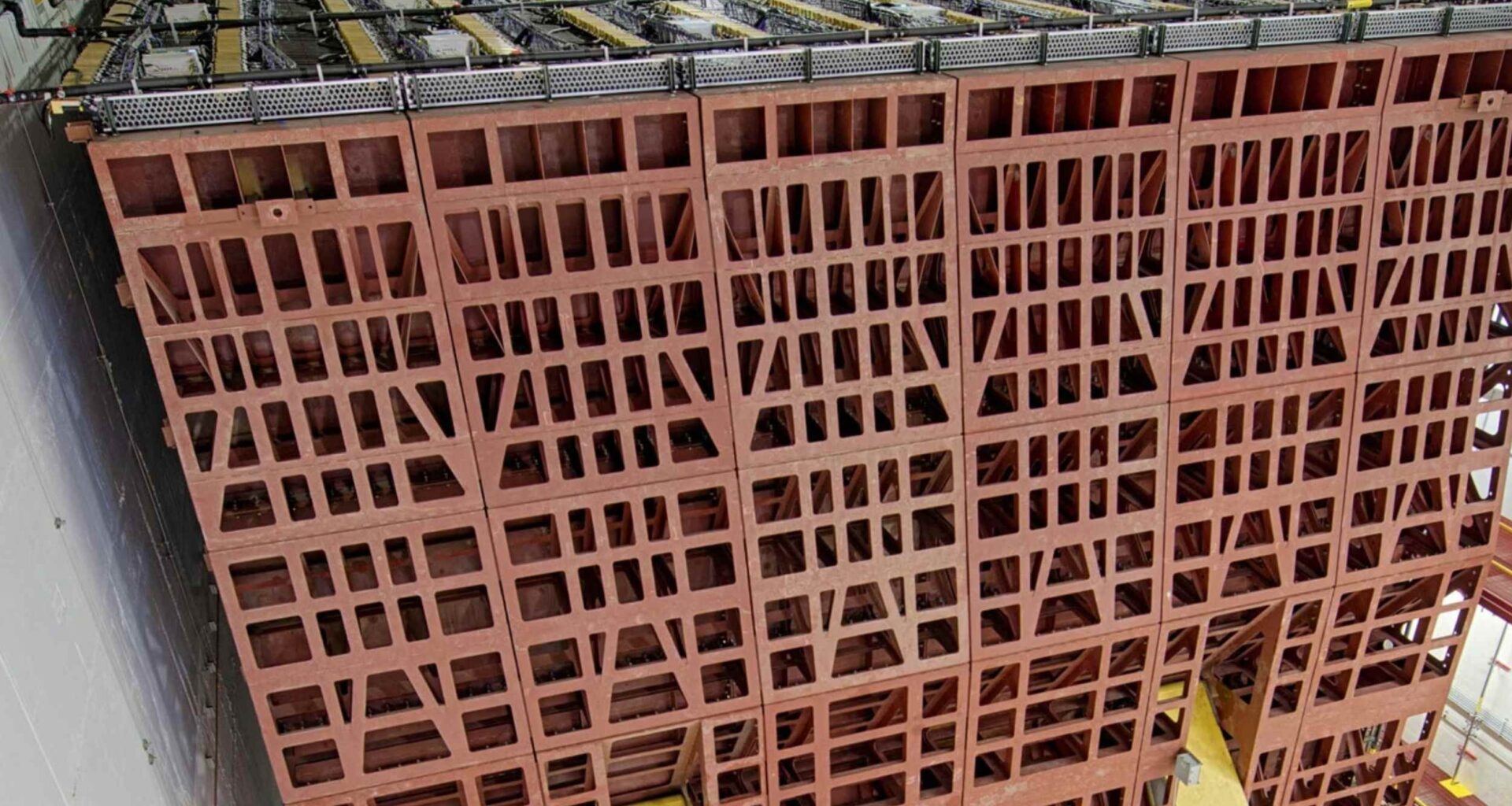

NOvA uses a 14,000-ton detector, 31 million pounds, made of cells filled with scintillator, a liquid that emits light when particles pass.

Super-Kamiokande sits about 0.6 miles (3,300 feet) underground, and Cherenkov light, blue flashes from fast particles, marks interactions.

NOvA-T2K measures the mass gap

One focus of the analysis is the mass gap that sets oscillation speed, especially for muon neutrinos in accelerator beams.

Physicists report a mass-squared difference, a number set by squared masses, because oscillations depend on that spacing.

Matching NOvA and T2K results squeezes the allowed range, because each experiment samples a different part of the oscillation pattern.

Even with improved precision, the analysis still cannot choose the ordering of the three neutrino masses.

One option has two lighter mass states and one heavier, while the other option flips that pattern.

Mass ordering guides how future experiments interpret oscillations, because the same data can mimic different physics under each ordering.

Neutrinos vs antineutrinos

Another test within the analysis asks whether neutrinos behave differently from antineutrinos, antimatter partners of neutrinos in the lab, during oscillation.

Antineutrinos often create opposite-charge particles, so sign tracking helps separate neutrino interactions from antineutrino interactions.

The matter mystery centers on why the universe is made primarily of matter instead of antimatter.

Separating two asymmetries

A key challenge for the analysis is separating a built-in neutrino difference from extra effects caused by travel through Earth.

Different baselines and energies help disentangle effects, because an oscillation pattern can come from either ordering or intrinsic asymmetry.

A violation of charge-parity symmetry, matter and antimatter reacting differently, could seed more matter than antimatter in the young cosmos.

What the data says

So far, the analysis showed that two different detectors can tell a consistent story about neutrino mixing.

Shared fitting methods let researchers compare systematic uncertainties across experiments, so disagreements could not hide behind separate assumptions.

Sharper neutrino parameters help designers predict event rates, which matters when detectors must wait years for enough interactions.

Next steps for NOvA-T2K

Despite progress, the analysis leaves open the biggest questions, and more data will be needed to rule out look-alikes.

Beam intensity, detector calibration, and background noise can all mimic an effect, so careful controls matter as much as size.

Both collaborations plan additional combined fits as new runs finish, and the broader neutrino program is gearing up for larger baselines.

Results from the analysis sets a benchmark that next-generation experiments can beat by collecting more events and longer distances.

Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment (DUNE) will send neutrinos about 800 miles through Earth to detectors in South Dakota, using a strong beam.

Japan is building Hyper-Kamiokande to start experimentation in 2028 with a much larger water detector.

As new data arrive, the analysis will be tested as new data arrive, especially where neutrino and antineutrino patterns diverge.

Clear answers will depend on patience and statistics, because the rarest events carry the strongest clues about fundamental physics.

The study is published in Nature.

Image credit: Reidar Hahn/Fermilab.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–