Arundhati Roy makes a striking confession early on in her luminous new memoir, Mother Mary Comes to Me. Explaining her reason for running away at the age of 16 from her home in Kerala and her mercurial mother, the renowned educationist Mary Roy, she writes, “We (she and her mother) settled on a lie. A good one. I crafted it—‘She loved me enough to let me go.’ That’s what I said at the front of my first novel, The God of Small Things, which I dedicated to her.” A tiny stab of fiction, framing a putative work of fiction.

When I meet Roy on a video call on a balmy August afternoon, it’s the first thing we talk about. As she writes towards the end of the book, the late writer, and Roy’s close friend, John Berger, never made a distinction between her fiction and non-fiction. “To pit one against the other, fact versus fantasy, is absurd,” she says. “As (the Italian filmmaker Federico) Fellini said, fiction is truth. Everything I write is a search for the form and language for this truth.”

In Mother Mary, Roy has to repeatedly reckon with the force behind this statement as the lines get blurred, often in unexpectedly hurtful ways. After Mary Roy read a passage in The God of Small Things (where the twins, Esthappen and Rahel, remember their parents fighting, pushing them from one to the other, saying, “You take them, I don’t want them”), she asked her daughter, “Who told you this?” When Roy said it was fiction, she retorted that it wasn’t—then she turned to the wall and fell silent.

View Full Image

Arundhati Roy after the Booker Prize award ceremony in 1997, which she won for her debut novel, The God of Small Things. (File photo/AP)

“There are things that I thought were fiction but turned out to be subconscious memories,” Roy, who is now in her mid-60s, tells me. “I am not even conscious of burying my pain.” In a sense, writing this book has been an exercise in trying to answer the questions that bother us all: Who are we? Where do we come from? What are our memories?

“I’m not someone who kept diaries or wrote down my thoughts—except once, after meeting my (estranged) father (Rajib ‘Micky’ Roy) for the first time as an adult,” she says. “What I really trusted, as I wrote this book, were feelings.”

Mother Mary Comes to Me, addressed to Mary Roy (or Mrs Roy as the children who studied at the school she set up in Kottayam had to call her), is a montage of a lifetime of feelings. It tells the story of how Suzanna Arundhati Roy, a quiet girl growing up under the severe regime of her mother, became Arundhati Roy, architect, scriptwriter, actor, world-famous author, and a voice against injustices around the world.

In her inimitable prose, playful and piercing by turn, Roy looks back on her life, with a disarming candour. In 1976, she arrives in Delhi as a naive young girl, meets her first love (a handsome, bearded architecture student she nicknamed “JC” for Jesus Christ), lives hand to mouth for a few years, before her peripatetic existence takes her briefly to Goa, where she and JC have a quasi-legal marriage.

Eventually she returns to Delhi, where she falls in love with filmmaker and naturalist Pradip Krishen (Pradip K in the book). She marries him, this time for real, scripts several avant-garde films with him, acts in a few, before throwing it all away to write The God of Small Things, which changes the very course of her life.

Most of her admirers are aware of this broad narrative. In Mother Mary, Roy fills up the gaps and interstices, revealing the brick and mortar that went into building up herself. “It’s been all an experiment,” as she puts it. “A living experiment—both my life and work.”

DISORDER AND EARLY SORROW

If The God of Small Things gives the reader a glimmer of Roy’s childhood in the sleepy village of Ayemenem in Kottayam, Mother Mary presents the full lay of the land—no holds barred.

Looming over little Arundhati’s life is the figure of her mother, a visionary educationist who founded the Pallikoodam School in Kottayam along with an Englishwoman, Mrs Mathews, in 1967. In 1986, Mary Roy became a national icon when she won a long-drawn legal battle to secure Syrian Christian women equal property rights with their male counterparts. That year, the Supreme Court invalidated the Travancore Christian Succession Act of 1916, which Mary had been a victim of, and applied the Indian Succession Act of 1925 to the Syrian Malabar Nasrani community of Kerala.

These towering feats, especially after she won her case against her brother G. Isaac (Rhodes Scholar, failed academic, and the inspiration behind the pickle baron in The God of Small Things) turned Mrs Roy into a living legend. She became a “gangster,” as her daughter calls her, with an outsized personality, a terrible temper and a knack for throwing choicest tantrums. “But she could be charming and charismatic, too,” Roy says. “Everybody knew, even those who were hammered by her, that the children in her school were getting a remarkable education.”

The beneficiaries of this education included Roy and her brother, both of whom bore the brunt of their mother’s rage—he far more than her, oddly for an Indian family, where boys are treasured over girls. It ranged from verbal abuse, to physical violence, to relentless emotional blackmail. In Roy’s stylised recounting, there is plenty of black humour in the story, including laugh-aloud moments, unbelievable as it may sound.

Mary Roy was severely asthmatic all her life, which left her children defenceless against her wrath. The slightest provocation could bring on a life-threatening attack. “The only thing was to walk away,” Roy says. “I was trained, from a very young age, not to respond, to hold it all in.” So Mrs Roy became “the sole keeper of the rage.” Her illness brought on terrible suffering, but it was also deployed tactically to keep everyone in line. “As one part of me was taking the hit, the other part was taking notes, metaphorically speaking,” as Roy says. “Maybe that’s what made me a writer.”

Reading about the cruelties and eccentricities of Mary Roy from our current awareness of mental health, it becomes apparent that she had a war raging inside her mind. But what’s more fascinating is her daughter’s steely resolve not to react, her refusal to cave in even when she is called names and hit by her mother. Except for one occasion, Roy never rose to Mrs Roy’s baits. She kept returning to Kottayam as an adult, quietly suffered her insults, jibes and humiliations, and looked after Mrs Roy till her last breath. “There was indisputably a light coming out of her school and her mission,” Roy says, “but for her to shine that light, my brother and I had to absorb the darkness.”

View Full Image

Pallikoodam School in Kottayam, founded by Mary Roy. (Pallikoodam School )

Ironically, a major part of Roy’s identity as a writer, and as a human being, is tied up with her compassion for the wronged, her anger against nefarious politics. Yet, she never seemed to have extended the same empathy towards herself—especially to the young girl who cowered under the shadow of a volatile parent.

One reason behind her lack of reaction was her strong awareness of her mother’s public battle for women’s rights. “I could see it not as her daughter but as a woman,” Roy says. “The second reason is that I left at 16 and stopped going home for a long time after I turned 18. It allowed me to not be destroyed by her or wholly judge the way she was with me. She taught me to be free and then raged against my freedom.”

This gift of freedom, complicated as it was, shaped Roy as the person she became, and Mother Mary commemorates that process with grace and gratitude.

FREEDOM TO BE

It’s easier to write about a parent who inspires unequivocal hatred. Jeanette Winterson’s Why be Happy When You Could be Normal? or Mary Karr’s The Liars’ Club are disturbing, hurtful, and as direct as memoirs can be. But it’s much harder to write about a parent, like Roy does, who inspired not hate, but rather left behind a trail of unresolved feelings. “I couldn’t make up my mind about her and I don’t think you can either,” Roy says . “But I wanted to share her with the world because I felt she belonged to the pages of literature.”

Although Roy acknowledges the existence of “a cult of Mrs Roy,” supplies all the ingredients that breathe life into the myth of Mary Roy, she never romanticises their relationship. It was a bed of nails from beginning to end, and it toughened her—left unsupervised from a young age, forced to find odd jobs to pay for her education and keep body and soul together. Above all, it liberated her from the fetters of expectation to look, dress and live in conformity with the morals of her class.

“Growing up on the edge of a community that made it clear that its protections and privileges were not meant for someone like me made me aware of a lot of things early on, even though I didn’t come from the bottom of the ladder,” Roy says. For a start, it afforded her “a lot of freedom” inside her head. Whereas 16-year-olds now have their brains filled with the noise of social media, in the 1970s, Roy grew up with the freedom to make herself exactly the way she wanted—with no influencer breathing down her neck, telling her what to do or how to look.

“The idea was to create your fashion, make your own clothes, as opposed to choosing from the one thousand styles that are being offered these days on the internet,” she says. “There was something freeing and lovely about it, even though what we had may have been moth-eaten.”

For her, it did not feel like a stigma to not be a moneyed person. From her early years, as the daughter of a single mother who rebelled against the system, in fact her own family, Roy had been told she didn’t belong—so, as a young woman, she decided to “cultivate an attitude to survive her not-belonging”.

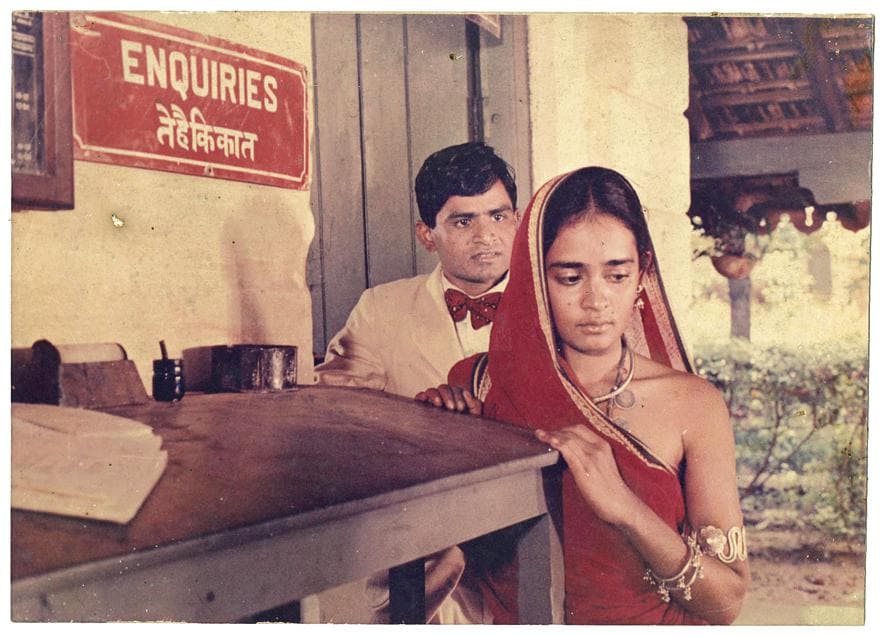

View Full Image

Arundhati Roy in the 1985 film, Massey Sahib.

She formed lifelong friendships and solidarities during her early years in Delhi that fortified her against the rough winds. In a sense, her life began to look like her mother’s “sliding-folding school” in Kottayam (in the 1960s, the school operated from the local Rotary Club premises during the day, then packed up for the members in the evening, only to unfold all over again in the morning, hence the name). It was frugal, portable, always ready for adversities and to be on the move.

Roy refused to embrace the norms of conjugality even after her marriage to Krishen. “Women are railroaded into one way of thinking about their lives,” she says. “While I have nothing against convention, I have a manifesto that says, you don’t have to do the conventional thing.” So, instead of being a regular parent to her stepdaughters, she became their “Noonie,” someone who loved, cared for, and supported them unconditionally, without ever acting as a forbidding, disciplining agent in their lives.

Roy’s relationship with money, too, has been far from conventional. She writes about it openly in the book. “Most people elide it, but it’s important for me to address money because it is part of my politics,” she says. “There was a time when I couldn’t sleep at night wondering how I was going to make it through another day, and then, suddenly, there was far too much money, which I didn’t have to do anything to earn.”

All through her life, Roy has lent her voice to many causes, including the Narmada Bachao Andolan and the Maoist struggle, but she is clear that she doesn’t believe in charity. She doesn’t want to set herself up as a “patron saint”, though she does want to enable other people to do beautiful and important work, which may not have any commercial value. The Zindabad Trust, which was set up by her and friends after she won the Booker Prize, makes it possible for writers, journalists, activists and others to continue doing meaningful work.

View Full Image

All through her life, Arundhati Roy has lent her voice to many causes. (File photo/AP)

In spite of all the adulation Roy receives from all over the world, she remains firmly grounded to her reality. It would have been easy for her to move abroad, start a life there, continue writing, and build a career, as so many Indian writers of the diaspora have done. But that would have been unnatural, a betrayal of everything she holds dear.

“Of course, there are times when I feel unsafe, but I also operate from inside many spaces and solidarities. Even though I work alone, I am not a lone agent. Rather, I’m nourished by so much support and counter-support,” Roy says. “For me, to live away from India would be like asking a tree in a forest to move to another forest—I’d lose my leaves. I have friends here who are in jail, I have friends in Kashmir, my life here is the blood and marrow of what I do.”

If there is a lesson to be taken from Mother Mary, it is this—her quest for new ways of living, thinking about money and literature, connecting with others continues to this day. “The fact that I’m angry at the establishment comes from love,” she says. “My anger comes from wanting to live in a more decent society, from the acknowledgement that ours is egregiously indecent society in so many ways.”

But there is no grandstanding, no false hope either. All we can do is try to live ethically—“try” being the operative word, she says. “We pay our taxes, they use it to make weapons, take out their rallies and build dams. You sign up to BDS (Boycott, Divest and Sanction, a non-violent Palestinian-led movement) but every aspect of your life may not fit in with it. All you can do is try, because once you become perfect, you become unbearable,” Roy says.

The years of her life, with all their ups and downs, the love she gets from her readers (“they are my protection”), and the bile that she continues to draw from her detractors, have only stoked her appetite for new adventures. “For me, the safest place in the world is also the most dangerous, and if it’s not, I make it so, because security suffocates me,” Roy says. “I’m always ready to light a few fires.”