Title: Radio emission from airplanes as observed with RNO-G

Authors: The RNO-G Collaboration

S. Agarwal, J. A. Aguilar, N. Alden, S. Ali, P. Allison, M. Betts, D. Besson, A. Bishop, O. Botner, S. Bouma, S. Buitink, R. Camphyn, J. Chan, S. Chiche, B. A. Clark, A. Coleman, K. Couberly, S. de Kockere, K. D. de Vries, C. Deaconu, P. Giri, C. Glaser, T. Glüsenkamp, H. Gui, A. Hallgren, S. Hallmann, J. C. Hanson, K. Helbing, B. Hendricks, J. Henrichs, N. Heyer, C. Hornhuber, E. Huesca Santiago, K. Hughes, A. Jaitly, T. Karg, A. Karle, J. L. Kelley, J. Kimo, C. Kopper, M. Korntheuer, M. Kowalski, I. Kravchenko, R. Krebs, M. Kugelmeier, R. Lahmann, C.-H. Liu, M. J. Marsee, Z. S. Meyers, K. Mulrey, M. Muzio, A. Nelles, A. Novikov, A. Nozdrina, E. Oberla, B. Oeyen, N. Punsuebsay, L. Pyras, M. Ravn, A. Rifaie, D. Ryckbosch, O. Schlemper, F. Schlüter, O. Scholten, D. Seckel, M. F. H. Seikh, J. Stachurska, J. Stoffels, S. Toscano, D. Tosi, J. Tutt, D. J. Van Den Broeck, N. van Eijndhoven, A. G. Vieregg, A. Vijai, C. Welling, D. R. Williams, P. Windischhofer, S. Wissel, R. Young, A. Zink

First Author’s Institution: Erlangen Centre for Astroparticle Physics (ECAP), Friedrich-Alexander-University Erlangen-Nürnberg; Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron DESY

Status: Published in the Journal of Instrumentation [open access]

Neutrinos: Long-Distance Travelers

If, in the middle of an intercontinental flight, you’ve ever looked out your window over, say, Greenland and wondered how this trip still isn’t over…just remember that your long-distance travels have nothing on the neutrino’s. This particle only very rarely interacts with other matter, so it can travel far across space without being absorbed or knocked off its original course. That makes neutrinos very valuable as astronomical messengers – provided you can catch some.

Tuning In To Neutrinos With A Radio Array

If enough neutrinos pass through a dense medium, like ice or water, every now and then one will interact with the medium and produce a shower of charged particles which create a cone of glowing blue Cherenkov radiation. If you outfit a large volume of ice or water with light detectors, you can watch for the blue light and reconstruct the paths and energies of the neutrinos. This is how neutrino observatories like IceCube and KM3NeT work, using Antarctic ice or Mediterranean seawater, respectively.

Today’s paper comes from a new neutrino observatory, the Radio Neutrino Observatory in Greenland (RNO-G), which is specifically designed to observe neutrinos with energies above 10 PeV (1016 eV), aptly known as ultra-high energy (UHE) neutrinos. UHE neutrinos should be created by ultra-high energy cosmic rays (UHECRs), and the astrophysical sources of UHECRs are…active galactic nuclei, or pulsars, or gamma ray bursts, or something else? Astronomers really aren’t sure and would like to find out! To date, only one neutrino with an energy above 10 PeV has ever been detected (that 220-PeV record-holding neutrino was announced this spring), and we need a lot more than one to understand them. The problem is that the higher the energy of the neutrino, the fewer there are. You’d have to cover an impractically large volume of ice or water to detect a statistically sufficient sample of UHE neutrinos via optical-light detectors.

Luckily, besides creating blue Cherenkov radiation, the particle showers caused by neutrino interactions also create distinctive radio pulses called Askaryan radiation. The neutrino has to be at least 1 PeV for the radio pulse to be noticeable with even really good radio receivers, but that’s okay if those are the neutrino energies you’re interested in! Moreover, while glacial ice is very transparent to optical light, it’s even more transparent to radio waves. That means you can space radio receivers farther apart, so it becomes practical to cover a much bigger volume of ice and thus detect more UHE neutrinos.

Now, Where Did I Put That Antenna?

RNO-G plans to deploy 35 stations (eight are up so far) of antenna strings, spaced 1.25 kilometers apart and extending 100 meters down into Greenland’s ice sheet, to listen for any neutrinos that come by. In order to know what direction the neutrino came from, you need to know the precise positions of your antennas…which is a little bit difficult, once you’ve buried them in 100 m of ice! Calibration pulsers are included on the strings, but they’re buried in the ice too and there are a lot of variables: besides three position coordinates per antenna, there’s the time data takes to travel up the strings and the varying, unknown index-of-refraction profile of the ice. In order to solve the whole math problem, it would be really nice to have a radio source far away from the antennas which can illuminate multiple stations at once – and one you can use for repeated calibrations, since ice moves and snow accumulates.

You could fly a drone with a calibration source over your array, but that’s difficult and expensive for a big array. You can use radio solar flares, but you don’t always have a solar flare when you need one. But you know what flies right over Greenland all the time and makes a ton of radio emissions for free? Airplanes! Here, the authors explore using airplane radio emissions for calibration of the array.

Examining Plane Waves

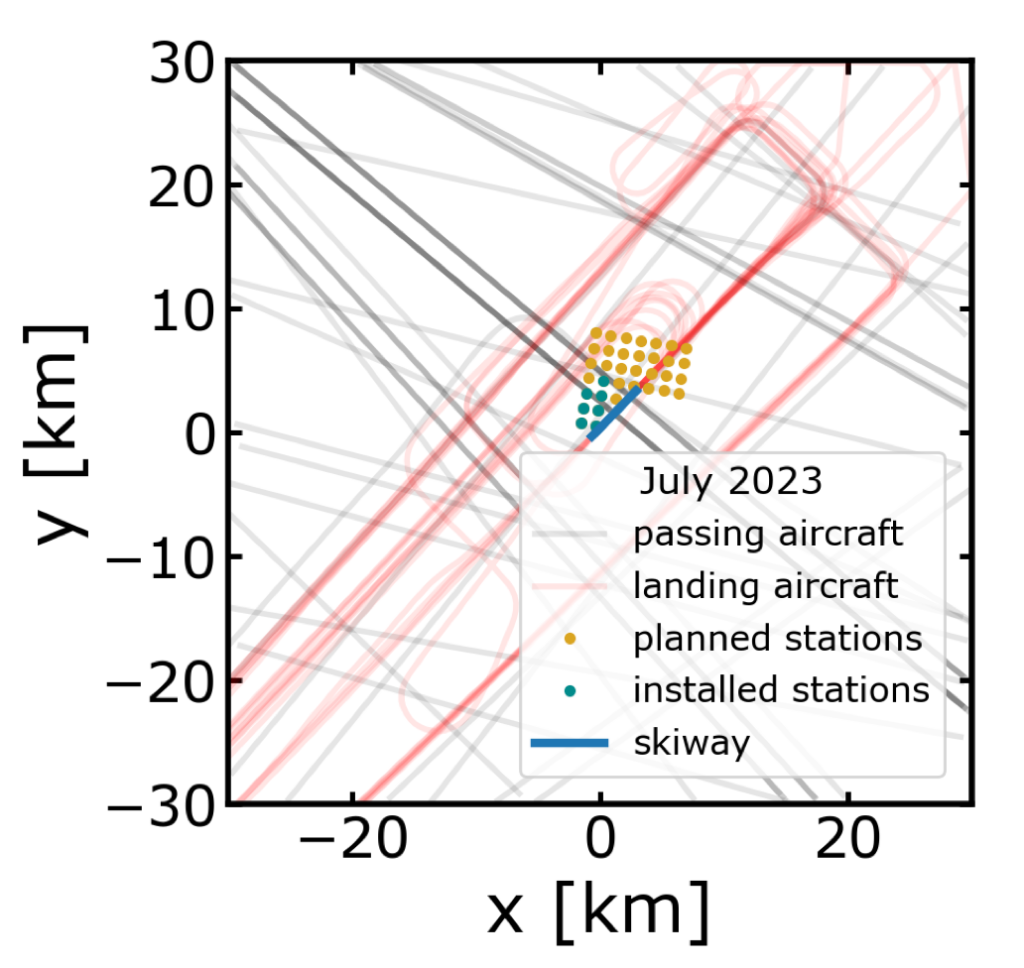

First, the authors see what airplane data they have to work with. Most aircraft continuously transmit their position and other information via the ADS-B system, so RNO-G installed an ADS-B receiver to identify all the flights that come within 50 km of the array and their trajectories. Between summer 2021 and summer 2024, that turned out to be over 8000 flights, by more than 1000 different airplanes! The most common subset is Japan-Europe flights passing overhead, but planes landing at the research station are also an interesting subset. Fig. 1 shows a map of all the flight paths recorded one month.

Fig. 1: A map of all the flights recorded near RNO-G in one month, July 2023 (source: figure 1 of today’s paper)

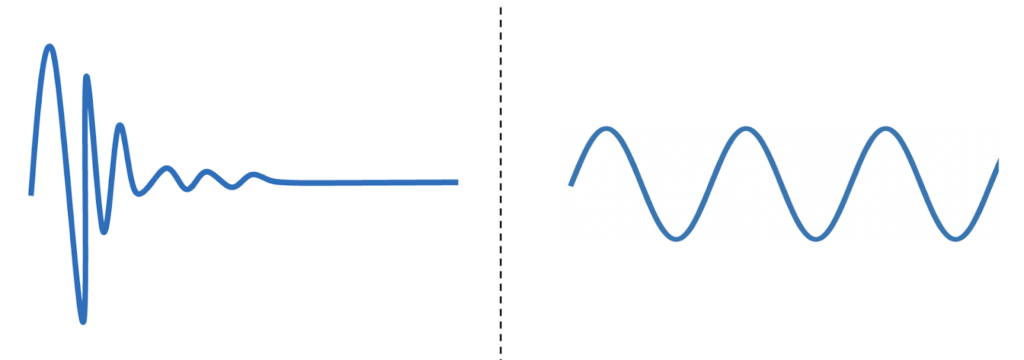

Next, the authors looked at the shapes of the signals seen by the antennas at times when planes were overhead. Because aircraft emit radio waves in a lot of different ways – airplane-to-airplane communications, ground-to-airplane communications, radar, unintentional radio noise from engines, and so on – the signals are complicated shapes and depend on the configuration of that specific airplane. Radio signals can be more impulsive – more burst-like – or closer to continuous-wave (CW) signals (see fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Left, a more impulsive signal waveform; right, a continuous-wave signal waveform.

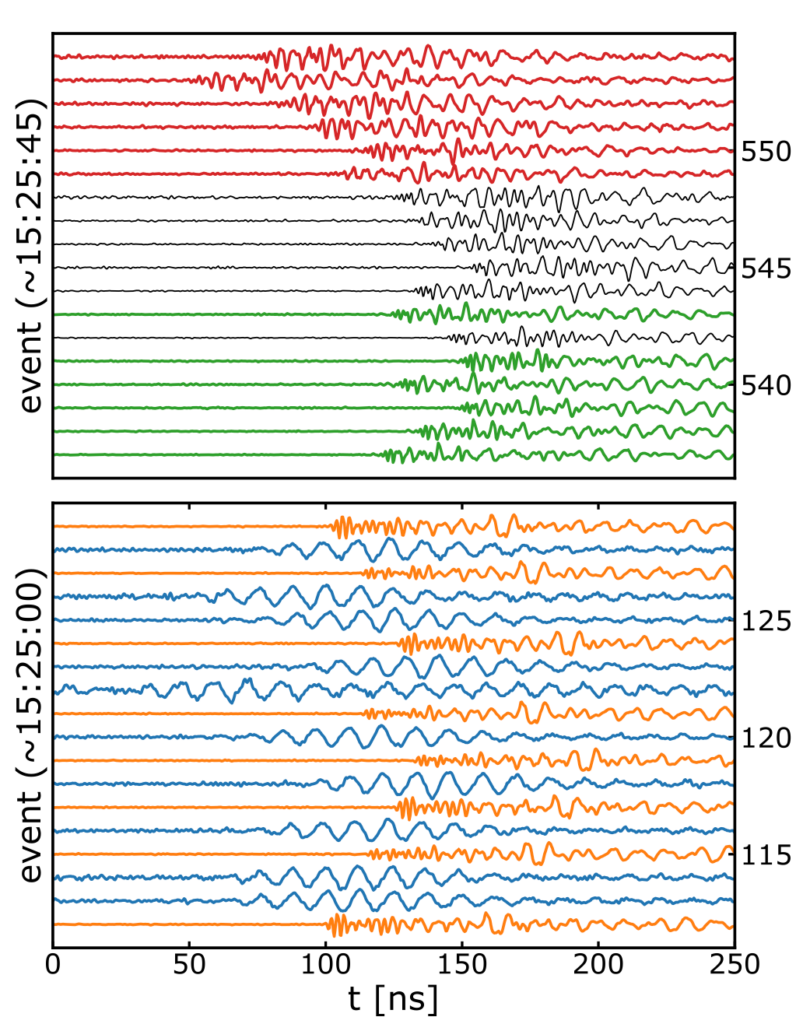

Signals with a higher degree of impulsivity are more useful for calibration because they have well-defined start times. Strong CW signals are identified and removed from the data, but there are plenty of impulsive signals. The authors also explore how to classify and group repeated signal shapes from the same airplane, discuss how different types of antennas in the array see the airplane signals differently, and consider how the array’s trigger settings for recording data interact with the airplane signals. You can see some examples of the signal shapes in figure 3.

Fig. 3: Some signal shapes seen by one antenna in RNO-G as an airplane landed at the research station. The different colors represent different groups of similar signal shapes identified by a cross-correlation algorithm. (Source: figure 7 in today’s paper)

Next Destination?

The authors conclude that the airplane signals they recorded are plentiful and come in useful shapes for calibrating the RNO-G antenna positions, and they plan to use the airplane radio emissions in the comprehensive calibration of the array. The approach could be useful for other neutrino observatories as well. IceCube, the neutrino observatory at the South Pole, plans to eventually add a radio array. While no commercial flights go anywhere near them, this paper includes a diagram of how supply flights to the South Pole could make a helpful little circle over their radio array before landing.

So, if you’re ever bored in the middle of a long intercontinental flight and see Greenland down below, just remember that you’re helping science – and wave, because something down in the ice is watching you!

Astrobite edited by Lindsey Gordon

Featured image credit: Sarah Stevenson