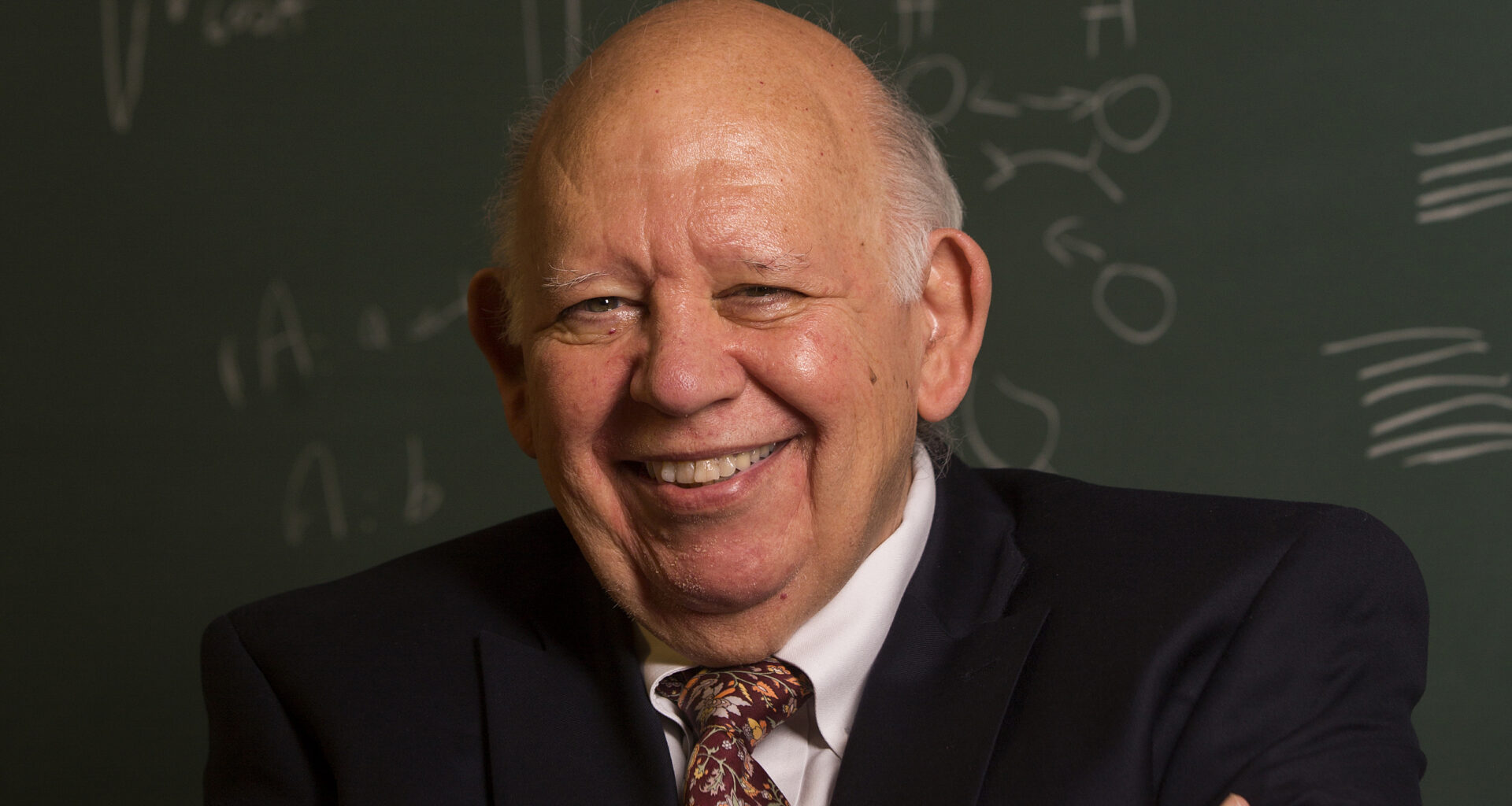

Donald G. York, an astronomer with the University of Chicago who helped revolutionize the field as a co-founder of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey and made pioneering contributions to the study of the interstellar and intergalactic mediums, died Dec. 26 at the age of 81.

York was the Horace B. Horton Professor of Astronomy and Astrophysics Emeritus at UChicago and the survey’s founding director, overseeing one of the most impactful astronomical projects of the 21st century.

The survey releases its data publicly for anyone to use and has contributed to more than 12,000 scientific papers to date. The American Astronomical Society called it “one of the most important and transformational facilities in astronomy.”

“Along with so much more, Don was a visionary,” said longtime friend and colleague UChicago Prof. Rich Kron. “Sloan Digital Sky Survey data are so rich in content that discoveries are still being made even with observations from the early 2000s. It democratized ground-based optical astronomy—astronomers at any career stage, anywhere, could participate in research. Thanks to Don’s vision and leadership, SDSS changed how astronomy is done.”

Astronomers around the world have used the Sky Survey to discover and dig deeper into wondrous things about the universe, including that every massive galaxy has a black hole at its center; that galaxies have dark matter “halos” around them; and that the Milky Way has many dwarf companion galaxies around it.

But despite the runaway success of the survey, York’s dedication to collaboration, teaching and mentoring, including at Chicago Public Schools, never wavered, his colleagues said.

The space between stars

Born in 1944 in Shelbyville, Illinois, York grew up searching for arrowheads and fossils on the banks of the Kaskaskia River, playing high school football, and tinkering in his uncle’s woodshop and photography darkroom.

He received his undergraduate degree at MIT in 1966 and his Ph.D. in 1971 from UChicago, where he worked at Yerkes Observatory. He then moved to Princeton University to join a team led by Lyman Spitzer, known as a founder of the Hubble Space Telescope, which was working on the NASA satellite Copernicus.

Copernicus launched successfully in 1972; York was lucky enough to observe its first star. “I was at the satellite controls for that event, certainly the high point of my young scientific life,” he would later write in his scientific autobiography.

In 1982, York joined the faculty at UChicago, where he would remain for the rest of his career.

York was interested in exploring not just stars and galaxies, but what existed in the space between them: clouds of gas and dust known as the interstellar medium and intergalactic medium. York began mapping the makeup of the interstellar clouds of the Milky Way, including the first detection of an isotope of hydrogen known as deuterium in these clouds—giving astronomers their first inklings that there is far less visible matter in the cosmos than there is other stuff, which we now call dark matter and dark energy.

He helped build a new observatory in New Mexico, the Apache Point Observatory, and oversaw the construction of a telescope with a then-groundbreaking setup that allowed scientists to easily attach and swap out different instruments and to use the telescope to observe remotely via computer networking from anywhere in the world.

But as they worked to understand the cosmos through astronomy, York and several colleagues, including Kron and Princeton Prof. James Gunn, began to feel they had a problem:

Astronomy was “data-starved,” York said.

‘Everyone said we were crazy’

At the time, astronomers generally worked alone or at most, in teams of a few people.

A scientist would think of an idea and apply for time on a telescope to investigate that specific idea; the data she gathered might or not be published. And science was beginning to ask bigger questions, such as how the structure of the modern-day universe was influenced by the Big Bang, that could only be answered by mapping hundreds of millions of objects in the sky.

How much easier it would be, York, Kron and Gunn imagined, if there was one central telescope that systematically scanned the sky and released calibrated and standardized data publicly, for any scientist to use.

“Our idea was that this would be a dedicated project, with everyone pooling resources and all the data would be available to everyone involved,” York would later say. “Everyone said we were crazy.”

“We had no idea what it would actually become.”

Starting from a series of meetings at O’Hare Airport, the outline for what would become the Sloan Digital Sky Survey evolved.

It was an uphill battle. There was no precedent for how to handle that much astronomical data; no framework yet existed for hundreds of astronomers working together (York would later describe the process as “herding cats”); and funding agencies were shy at first.

But eventually, hundreds of scientists and multiple institutions joined; funds were secured to build a second telescope at Apache Point Observatory dedicated to the Sky Survey; and innovative techniques were created to house and distribute the data.

York served as the Sloan Digital Sky Survey’s founding director. Key parts of the equipment for the telescope were built at both Yerkes Observatory and on campus; the design strung together many charge-coupled device (CCDs), in an arrangement that would eventually revolutionize observational astronomy.

The project began taking data in 1998, which it calibrates and releases periodically for public use—anyone can download the data and use it for studies. Since then, these data have enabled scientists to make thousands of discoveries about everything from black holes to supernovae to the ripples from the Big Bang.

York would use data from the survey and other instruments (including the space-based International Ultraviolet Explorer and the Far Ultraviolet Spectroscopic Explorer) to pursue his own scientific questions, including unidentified diffuse interstellar bands and cataloguing the spectra of quasi-stellar objects to study the three-dimensional distribution of intergalactic gas.

But colleagues said his legacy far outstrips individual scientific discoveries.

“Don York is an inspiration to all of us,” said York’s colleague Prof. John Carlstrom, who led the collaboration that built the South Pole Telescope and cites the Sky Survey as a critical precedent. “His leadership in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey led to what is arguably the most impactful observatory ever built.”

“Astronomers and citizen scientists all around the world owe Don a tremendous debt for his leading role in bringing not only this project, but this mode of maximally accessible and radically collaborative astronomy, into existence,” said Juna Kollmeier, current director of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, now in its fifth phase. “We remember him with gratitude.”

‘The chance I have had in life is rare’

Colleagues remembered York as a warm and welcoming presence in the department. “He really set a tone of collegiality that remains with us,” said Prof. Rocky Kolb.

York co-founded the Chicago Public Schools/University of Chicago Internet Project, which brought the Internet to 24 schools in the University’s neighborhood. In 2000, the South East Chicago Commission awarded him its Community Service Award, and the UChicago Neighborhood Schools Program named its annual award the Don York Faculty Initiative Award in honor of his contributions.

Asked why he devoted so much time to public schools, he told the University of Chicago Chronicle in 1997 that as a product of public schooling, he felt strongly about it.

“My mother raised three children on Social Security and part-time employment,” he said. “The chance I have had in life is rare, so my involvement in the public schools is payback, if you will….Public schools are really the only vehicle that reaches into all corners of society.”

He published more than 590 peer-reviewed studies, which have accrued more than 81,000 citations, as well as The Astronomy Revolution: 400 Years of Exploring the Cosmos, with two co-editors, in 2012.

York’s awards include the Royal Astronomical Society Award for Public Service, the 2021 SIGMOD Systems Award, and the 2022 George Van Biesbroeck Prize. York also received the 2025 Norman Maclean Faculty Award for extraordinary contributions to teaching and student life at the University of Chicago. He was a member of the American Astronomical Society and the International Astronomical Union.

Outside of scholarly pursuits, York’s family said he loved the outdoors, hiking, camping and supporting his family, and was a longtime member of the Ellis Avenue Church and the Hyde Park Union Church.

He is survived by his wife Anna, to whom he was married for nearly 60 years; children Sean, Maurice, Chandler and Jeremy: grandchildren Lilia, Anika, Juliet, Samuel, Aeron and Jasper; and by his sister Diana. He was predeceased by his sister Carolyn.

A public memorial service is in planning for June.