15 Jan 2026

According to a recent study, the view that Alzheimer’s disease damages the brain irreversibly might need to change. In December 22 Cell Reports Medicine online, scientists led by Andrew Pieper of Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, report that boosting levels of the metabolic coenzyme NAD+ in two different Alzheimer’s disease mouse models prevents measures of disease in younger mice and normalizes them in older mice. Raising the mice’s supply of NAD+ with the compound P7C3-A20 rescued a lengthy catalog of pathologies and toggled protein levels away from aberrant signatures in mice and humans with AD.

- Small molecule P7C3-A20 restores NAD+ supply in AD mouse models.

- P7C3-A20 reversed pathologic changes in plaque, phospho-tau, blood-brain barrier structure, synaptic function, and behavior assays.

- P7C3-A20 flipped proteome changes in 5xFAD mice; some mirror alterations in people with AD.

- Next step: clinical development.

“Our results are very encouraging,” Pieper wrote to Alzforum. “Seeing P7C3-A20 reverse signs of disease in two different mouse models of AD, one driven by Aβ plaques and one by tauopathy, strengthens the idea that restoring the brain’s NAD+ balance might help people recover from AD.”

Russell Swerdlow, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, agrees with this idea. “This work supports the view that fixing dysfunctional bioenergetics or carbon fluxes within a brain can benefit that brain, potentially even those impacted by AD,” he told Alzforum.

Previously, Pieper, working at the time with Steven McKnight at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, had pinpointed P7C3 as a compound promoting neurogenesis in a drug screen in mice (Jul 2010 news).

Next came the question of whether boosting the brain’s NAD+ supply could have therapeutic promise in Alzheimer’s, as some of the manifold processes this metabolite is involved in go awry in the disease. NAD+ is central to ATP production, plus it performs non-enzymatic roles in cell signaling, DNA repair, epigenetic remodeling, and axonal health (Chini et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2021).

In this study, first author Kalyani Chaubey and colleagues tested a follow-up compound to the original P7C3, P7C3-A20, in 5xFAD mice. Pieper claimed this improved analog has “improved neuroprotective activity.”

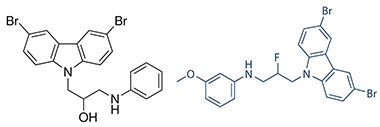

A Better Structure? Chemical structures of P7C3 (left) and the second-generation analog P7C3-A20 (right). [Courtesy of Andrew Pieper.]

The scientists injected mice intraperitoneally every day from 2 to 6 months of age to assess potential preventive effects in what they called the model’s “mid-disease” stage, and treated a separate group from 6 to 12 months to evaluate reversal of behavioral deficits and AD pathologies in more advanced disease. These mice survive for approximately 18 months (Nehra et al., 2024).

At 2 months, 5xFAD mice had NAD+ levels similar to wild-type. By 6 months of age, the former showed a 30 percent drop in NAD+ and by one year, 45 percent. P7C3-A20 treatment normalized NAD+ levels at both time points.

“P7C3-A20 safely stabilizes NAD+ homeostasis without elevating it to supraphysiologic levels. This is an important distinction from the mechanism of over-the-counter NAD+ supplements, which directly drive NAD+ synthesis,” Pieper wrote to Alzforum. Excessive NAD+ levels have been linked to numerous side effects, including cancer (Palmer and Vaccarezza, 2021).

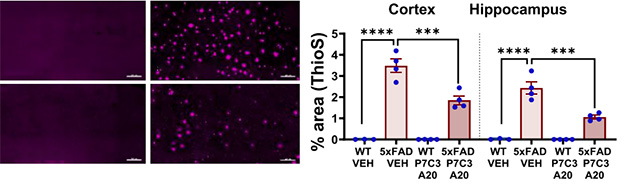

With P7C3-A20 treatment, total Aβ peptide did not change—as APP cleavage is independent of NAD+—but thioflavin-S staining of aggregated amyloid was reduced in treated mice (image below). In mid-disease, the drug did not alter the amount of total or phosphorylated tau, but it lowered phospho-tau in advanced-stage mice, with no change in total tau. P7C3-A20 affected neither Aβ nor tau in wild-type mice.

Plaque Preventor. Thioflavin-S staining (magenta) of 12-month-old wild-type (left column) and 5xFAD (right column) mice; P7C3-A20 treatment (bottom row) led to fewer plaques in the cortices (left graph) and hippocampi (right graph) of AD mice. [Courtesy of Chaubey et al., Cell Reports Medicine, 2026.]

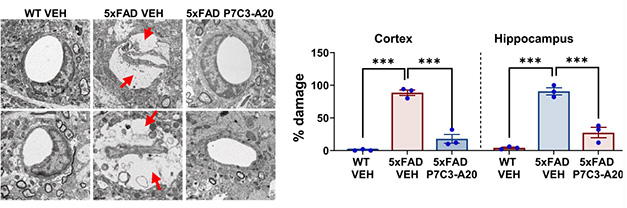

The scientists report that NAD+ restoration had other effects, as well. It repaired the blood-brain barrier, eased astrocytic and microglial inflammation, and shrank the number of DNA strand breaks. It preserved hippocampal long-term potentiation, a readout of synaptic health, in both mid- and advanced-disease stage 5xFAD mice.

More NAD+, Better BBB. Transmission electron microscopy of 12-month-old mouse cortices (top row) and hippocampi (bottom row) revealed wide gaps around vessels, a sign of barrier deterioration (red arrows), in 5xFAD vehicle-treated but not P7C3-A20 treated mice. [Courtesy of Chaubey et al., Cell Reports Medicine, 2026.]

The list goes on. For mice treated months 6 to 12, P7C3-A20 put the brake on neuronal death, as measured by immunofluorescence of the neuron-specific marker NeuN. In this age group, more newly generated hippocampal neurons survived, as per BrdU labeling. Tyrosine nitration and protein carbonylation, signs of metabolic stress, were up in both age groups of 5xFAD mice compared to wild-type; P7C3-A20 prevented and reversed this.

These biological changes came with behavioral benefits. Mice treated from months 6 to12 outperformed controls in a battery of tests for memory, learning, and anxiety.

The researchers found no sex-specific differences. Nowadays, most research groups consider sex as a variable in preclinical mouse studies, with some opting to use only the sex in which their observed effect is strongest (Miller et al., 2017).

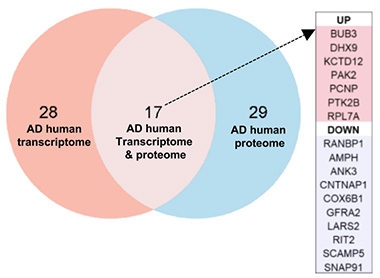

To explore how NAD+ restoration might work so broadly, the authors ran mass spectrometry proteomics of hippocampi from 1-year-old wild-type and 5xFAD mice. They found 174 proteins whose levels differed in the latter but were restored to normal by P7C3-A20. Comparing these with human AD brain proteome datasets, they saw that 46 were altered in the same direction in people with AD, and were also normalized in treated mice, highlighting conserved disease pathways. These 46 clustered into mitochondrial function, proteostasis, lipid handling, and immune signaling pathways.

A subset of 17 proteins also showed matching changes at the transcriptional level in AD human brains (image below).

Proteomic Priorities. Of the 46 proteins whose directional changes aligned in mice and humans with AD, and responded to P7C3-A20 in mice (right circle), 17 also overlapped at the mRNA level in humans (middle). Seven proteins were upregulated and 10 downregulated in people with AD. [Courtesy of Chaubey et al., Cell Reports Medicine, 2026.]

Making a point about resilience, the authors report that brain samples of people who remained cognitively healthy despite extensive AD pathology showed expression of NAD⁺-consuming enzymes similar to controls—and higher than in symptomatic AD.

Gregory Brewer, University of California Irvine, called age-associated metabolic decline the “elephant in the room.” He wrote to Alzforum that the AD field has been distracted by large genomic datasets that reflect downstream changes but do not reveal true upstream disease triggers. Without interventional studies like this, he wrote, it is difficult to distinguish disease byproducts from drivers (comment below).

This drug’s promise held up in a second model, the PS19 tauopathy mouse. Chaubey and colleagues injected P7C3-A20 at 11 months of age, near the end of this strain’s lifespan of about one year, and claim that it improved scores on cognitive performance tests, bolstered BBB integrity, and protected against DNA damage.

“Of course, the next step is a human trial,” Pieper told Alzforum. To do that, he co-founded Glengary Brain Health in Cleveland.

According to Pieper, future clinical trials, which are some years away, will show whether restoring brain NAD+ homeostasis is sufficient to achieve disease recovery, either by itself or complementary to other available therapies.

For Swerdlow, these results reignite the question of whether there is a point of no return for AD treatment. “To me, there is no definitive evidence that there is a time beyond which we can no longer intervene,” he said to Alzforum. “The real challenge is finding what we need to fix.”

In line with this, Pieper told Alzforum his team is currently exploring the intersection between their mouse models and findings from human AD brains to identify which processes best complement NAD+-homeostasis-based recovery from disease. They do not yet know the exact mechanism by which this compound acts.—Anna Bright

Anna Bright is a Ph.D. student in New York City.

News Citations

- Mouse Screen Yields Pro-neurogenesis Elixir 9 Jul 2010

Research Models Citations

Paper Citations

-

Chini CC, Cordeiro HS, Tran NL, Chini EN.

NAD metabolism: Role in senescence regulation and aging.

Aging Cell. 2024 Jan;23(1):e13920. Epub 2023 Jul 9

PubMed. -

Wang X, He HJ, Xiong X, Zhou S, Wang WW, Feng L, Han R, Xie CL.

NAD+ in Alzheimer’s Disease: Molecular Mechanisms and Systematic Therapeutic Evidence Obtained in vivo.

Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:668491. Epub 2021 Aug 3

PubMed. -

Nehra G, Promsan S, Yubolphan R, Chumboatong W, Vivithanaporn P, Maloney BJ, Lungkaphin A, Bauer B, Hartz AM.

Cognitive decline, Aβ pathology, and blood-brain barrier function in aged 5xFAD mice.

Fluids Barriers CNS. 2024 Mar 27;21(1):29.

PubMed. -

Palmer RD, Vaccarezza M.

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide and the sirtuins caution: Pro-cancer functions.

Aging Med (Milton). 2021 Dec;4(4):337-344. Epub 2021 Nov 30

PubMed. -

Miller LR, Marks C, Becker JB, Hurn PD, Chen WJ, Woodruff T, McCarthy MM, Sohrabji F, Schiebinger L, Wetherington CL, Makris S, Arnold AP, Einstein G, Miller VM, Sandberg K, Maier S, Cornelison TL, Clayton JA.

Considering sex as a biological variable in preclinical research.

FASEB J. 2017 Jan;31(1):29-34. Epub 2016 Sep 28

PubMed.