In 2011, I appeared on an RTÉ Radio documentary called #TwitteronTrial in which presenter Pat O’Mahony and a panel of Twitter afficionados tried to convince me of the worth of the four-year-old microblogging platform. On air, I sceptically set up a profile. In the succeeding months I learned its worth as a journalistic tool and proceeded to get addicted to its endless stream of breaking news, novelty and argument.

Two weeks ago, I deactivated that profile. I hadn’t posted there in some time due to changes Elon Musk had made to the platform since 2022, but I would check in occasionally. I was, by this point, unsurprised by the racism, misogyny and homophobia on the platform but I was not expecting the huge number of non-consensual deep-faked porn images users were posting of any woman or child whose image could be found online.

Twitter had, within years of its founding, re-engineered how global discourse worked. It was the place which helped foment the Arab Spring revolutions, where politicians and public figures made public announcements and where people went for a snapshot of current events. Within a year of Elon Musk’s purchase, it was a site riddled with bigotry where you couldn’t be sure you wouldn’t accidentally scroll past illegal content.

Twitter, originally Twttr (there was a vogue for vowelless company names), was conceived by Jack Dorsey in 2006 and spun off from Odeo, an audio and video start-up, in 2007. The idea was simple – a place where people could put up regular text-based status reports about what they were doing or thinking. It became a hub for a very different sort of conversation than those hosted on other social media sites.

The writer and broadcaster Jon Ronson was an early fan. “Everybody had a voice and I loved that,” he says. “Ironically it was actually Graham Linehan who first told me I should join Twitter, because he said it was a place where no one fights.” Linehan was later suspended under “hateful conduct” rules. “And that was true in the early days, partly because it was such a small community. It felt to me like one of those Robert Altman ensemble movies, like Shortcuts or Nashville. I loved the equality of it. I loved the fact that Stephen Fry might be [talking about being] stuck in an elevator, and then underneath that, some random person is talking about what they had for breakfast. I really liked that it was the tapestry of life unfolding.”

[ How rotten does X have to be before politicians finally leave it?Opens in new window ]

Despite being significantly smaller than Facebook, it attracted journalists, celebrities and academics and, as a consequence, its conversations started influencing the wider culture. “Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat are all more siloed social media experiences where you’re talking within a group of people that you know,” explains New York Times journalist Kate Conger who, with Ryan Mac, wrote Character Limit, about Elon Musk’s takeover of the company. “Twitter was a place where everyone globally could be in conversation with each other, for better or for worse. And whereas other companies had moved a long time ago towards an algorithmic decision-making process about what you see, Twitter stuck by the chronological narrative.”

This meant that Twitter always felt of the moment. Mark Little was a broadcaster on RTE’s Prime Time when he discovered the platform. “Whereas previously I’d been the voice of God [on TV] suddenly everybody was talking back. Quite a few would tell me I was a b****cks, but at the same time they would be telling me what I could do better … Twitter gave a whole new view of the authentic weirdness of the world. When I started to see the beginning of the Arab uprising or protests in Iran [on Twitter], it was way more real than any journalist could do credit to.”

Mark Little: People are ‘looking for ways to resist the algorithm’. Photograph: Dara Mac Dónaill

Mark Little: People are ‘looking for ways to resist the algorithm’. Photograph: Dara Mac Dónaill

At that stage, Little had established his own company, Storyful, which sifted through social media feeds for news. “There’s a narrative that set in, that it was just a big ego boost for journalists,” he says. “That’s bullsh*t. It had a big impact on the discourse because it was bringing in voices that never really had a coherent voice before. So, for example, there was a substantial group of black Americans who were coming together in a much more authentic conversation than anything reflected in the mainstream. And out of that comes really practical changes in society, like Black Lives Matter … With the Arab Spring people were using Twitter, not just as a place to talk, but a place to organise.”

Mainstream media quickly went from treating Twitter with suspicion to using it productively to following its controversies more lazily. And there were early controversies, such as Gamer Gate where hordes of online trolls harassed female game-creators and journalists. Jon Ronson was one of the first people to write about the darker, more punitive tendencies of the platform in his book, So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed. His “patient zero” for public shaming was a PR executive named Justine Sacco who tweeted a badly phrased joke before boarding a plane and had her life torn apart by thousands of people as she slept.

“Before Justine Sacco came along we were going after people where there was some justification, like Rupert Murdoch or a company that had committed an actual transgression … We fell in love with our shaming power too much. And instead of getting corporations that had actually done something wrong, we started targeting random individuals who had written a poorly worded tweet.”

Jon Ronson: ‘X is eating itself’

Jon Ronson: ‘X is eating itself’

Conger says the company knew a lot of people were afraid to post on the platform and this inhibited growth. “A lot of it was fear of harassment, fear of being called out, fear of being shouted down. And that was something that drove a lot of their decisions towards content moderation, because they wanted people to feel safe enough to post.”

The company also, she says, “struggled to make its case to advertisers why it might be as valuable a place for them to be as Facebook or Instagram.”

In 2016, in an attempt to monetise more effectively, Twitter introduced an algorithmic feed. “That’s the day that Twitter stopped being a social network,” says Little. “What an algorithmic feed does is pick up the emotional power of a tweet and it then just inserts it, without me asking for it, into my feed. It becomes a fun house mirror. There was a study last year that shows the vast majority of toxic content is produced by a tiny, tiny fraction of people and the reason they have oversized impact is because of the algorithm.”

While all this was happening Donald Trump’s presidency was providing a huge challenge for the platform. He was repeatedly breaking the company’s moderation rules regarding hate speech, but they felt they couldn’t ban him, only doing so after his role in stirring up insurrection on January 6th, 2021. Parag Agrawal replaced the dreamy and distant Dorsey as chief executive later that year (Dorsey had already left and returned to the fraught company once before).

Jack Dorsey, Twitter’s co-founder and former chief executive. Photograph: Bryan Thomas/The New York Times

Jack Dorsey, Twitter’s co-founder and former chief executive. Photograph: Bryan Thomas/The New York Times

Meanwhile, one of the site’s most prolific tweeters, the world’s richest man, Elon Musk, was being radicalised by Covid policies and was taking issue with Twitter’s moderation decisions. He began secretly buying up shares before buying the company outright and taking it private in April 2022 for a mind-blowing $44 billion (Conger’s book contains a detailed account of all this that’s well worth reading). This was the moment, in Little’s view, that Twitter became an explicit “political project”.

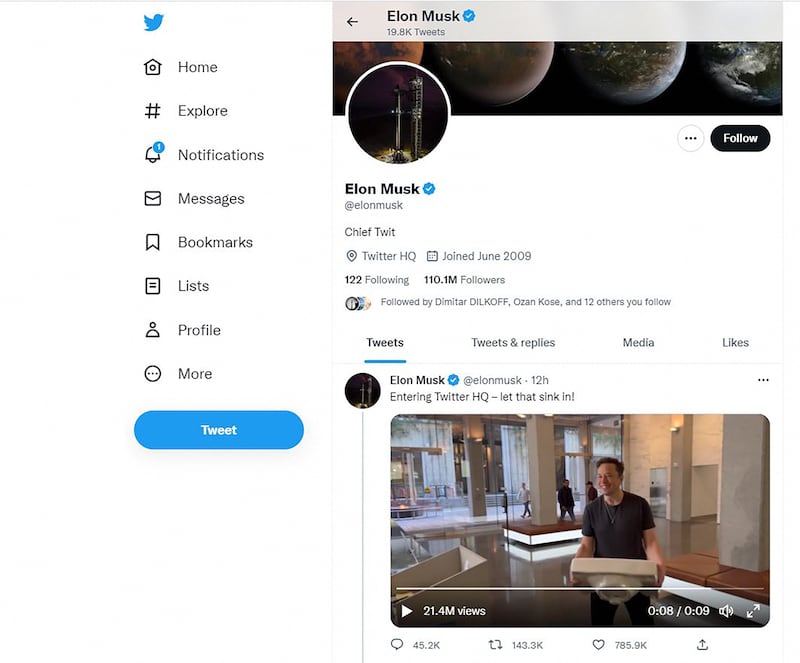

Musk turned up carrying a kitchen sink so he could tweet the phrase “Let that sink in.” He instantly began chaotically firing staff members, most notably on the safety side of the organisation. He renamed the platform “X”, a long-favoured company name, and began tinkering with its systems to reduce moderation, boost his preferred content and reduce the reach of mainstream sources. He also changed the “blue tick” system into a paid service. Formerly, this feature confirmed a user was who they claimed to be. Now, says Conger, “it indicates you own a credit card”.

[ Blue checks on X deceiving users into engaging with harmful material, EU saysOpens in new window ]

What was Musk trying to do? “He wanted to turn it into his own playground, his own ideal social media experience,” says Conger. “Everyone paying attention to him and noticing him and engaging with him … Content that he likes and wants to see are everywhere in the feed and content he doesn’t like isn’t present. It’s really shifted from being something that can cater to global taste to something that caters very closely to Elon’s personal taste.”

By undermining experts, enabling engagement-farming accounts and allowing the return of once banned trolls, he also turned the site into a hotbed of abuse and misinformation. “The day Elon Musk bought Twitter, he tweeted or retweeted, that Nancy Pelosi’s husband, who’d been beaten almost to death, was a participant in a sex game gone wrong,” notes Ronson. “That was the loudest alarm bell. Cut to today, and you’ve got people [using Grok] undressing Renee Good’s dead body and putting her in a bikini as she’s lying slumped dead in the car.”

Has this upsetting content deterred users? “It’s really hard to tell, because they’re no longer a public company,” says Conger. “Nikita Bier, their head of product, recently put out a couple of graphs saying [they had] their highest engagement ever … [These graphs] coincided with the assassination of Charlie Kirk and this recent nudification issue. He hasn’t directly linked X’s engagement to those incidents, but I think it’s hard to look at these spikes in traffic and not see a correlation.’”

Twitter is now a very different platform with a different name. Many former users feel it no longer provides real time insight into events or meaningful connection with others. Nothing else has successfully taken up that role, says Conger. “I don’t think there’s a platform that has the same finger on the cultural pulse that Twitter once had.”

Screen grab of the Twitter account of billionaire Tesla chief Elon Musk on October 27th, 2022. Photograph: AFP/Twitter/Getty

Screen grab of the Twitter account of billionaire Tesla chief Elon Musk on October 27th, 2022. Photograph: AFP/Twitter/Getty

This is partly because people increasingly want something different from social media, she says. “We’re at the early stages of a really big sea change … We’ve been seeing people post less and less on social media for a long time … I think people are moving to more private social experiences, whether that’s within a private group chat or within a closed Instagram profile. [Younger people] have more street smarts about what they’re putting on the internet.”

Mark Little points towards “a rewilding movement where people are going back to the old forums of the old internet, back to Reddit, recreating the open and collaborative communities [of the past]. They’re looking for ways to resist the algorithm to move to what people are calling ‘dark forests’ that can’t be scraped by the algorithm, can’t be scraped by the AI. [They’re] leaving the big social media platforms to find communities where they’re safe and there’s civility.”

Ronson says any predictions he makes about the future of social media might be wishful thinking. He recalls his friend, BBC documentarian Adam Curtis, likening the internet to “a John Carpenter movie with all of these warrior gangs battling in the streets. Most people are going to want to move to the suburbs to get away from it. Maybe there will be a return to institutions.”

And what will ultimately happen to X? “I think X will basically fade into the background as a reflection of the anger and disillusionment that’s out there,” says Little. “X is 1768731308 a place where you throw your view into the ether and you get nothing back except rage. It’s eating itself.”

It’s an important lesson, he says. “The big mistake a lot of people made was they thought that social media was inherently democratic. It wasn’t. Technology is neither good nor bad. When Obama comes along and says, ‘Yes, we can,’ we all think social media is going to be a power for democracy. [Then] Donald Trump comes along and said, ‘So can I.’ This technology is not inherently democratic. I think that broke the hearts of many people.”