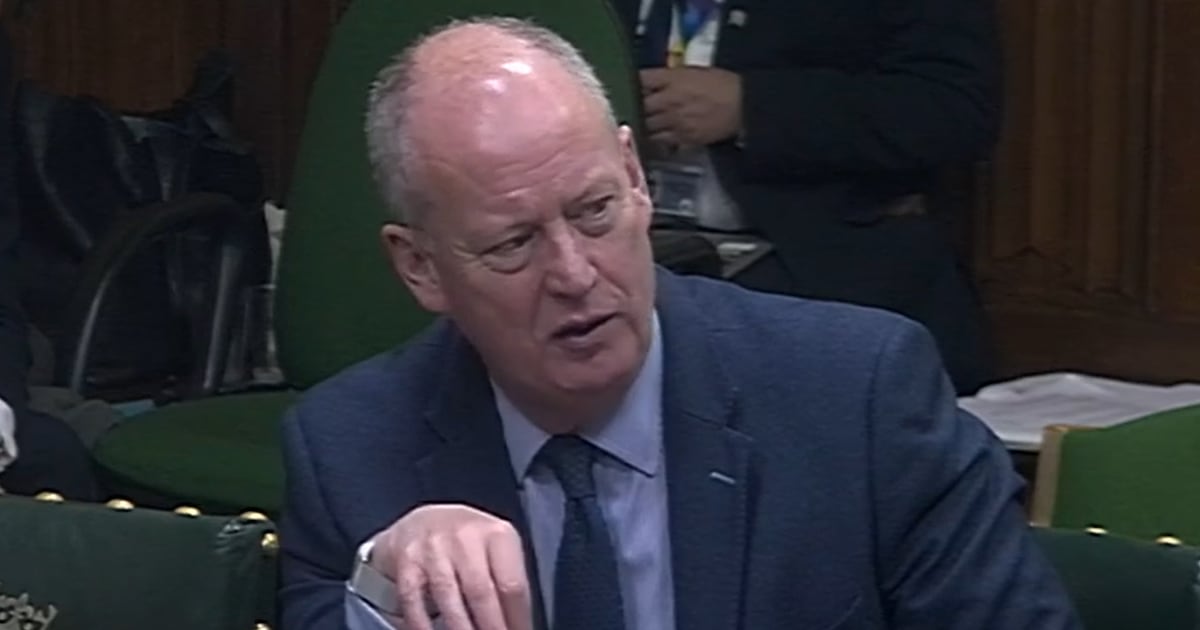

Loyalist paramilitaries were often behaving as “community workers by day and terrorists by night”, former Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) chief constable George Hamilton has told a Westminster committee.

Mr Hamilton, who led the PSNI from 2014 to 2019, said loyalist communities must be empowered to resist the influence of paramilitaries in their neighbourhoods who ruled by fear and intimidation.

Though supportive, Mr Hamilton and his predecessor Hugh Orde raised doubts about the likelihood of success of the new investigation into the existence of loyalist groups set up by the Irish and British governments last September.

Fleur Ravensbergen, an independent conflict-resolution and negotiation expert, was appointed to assess whether there was merit in and support for formal engagement with the paramilitary groups to bring about their end.

Some security briefings suggest the Ulster Defence Association has up to 12,000 members today – more than it had at the time of the 1998 Belfast Agreement, though many are said to be “card-carrying only”.

“A lot of these people are still behaving in the same coercive, controlling way around their communities,” Mr Hamilton told the House of Commons Northern Ireland Affairs Committee on Wednesday..

“These groups are not legitimate, but they do have extensive control within communities, so their view of policing is burning out the drugs house, but it’s probably going to be a drugs competitor that they’re burning out.”

Such coercive control “undermines the ability of the police to operate if there is an alternative policing faction essentially operating within the community”.

Mr Hamilton and Mr Orde both said the costs attached to legacy investigations and any subsequent legal claims must be completely separated from today’s PSNI.

“The funding needs to be completely separated out from policing because it’s just a constant suck on money,” Mr Hamilton said.

Operation Kenova, the long-running investigation into the activities of Freddie Scappaticci, the British Army spy in the Provisional IRA, cost more than twice as much and lasted twice as long as originally thought, he said.

Mr Orde strongly defended the Historical Enquiry Team (HET) he set up to investigate legacy cases, which was eventually brought down by a sharply critical report from HM Inspector of Constabulary in 2015.

Still clearly angry about the closure of the HET, Mr Orde said he remained “very proud of the work they did” and the information about killings that they were able to share with victims’ families.

“We told the families whatever we found out, which for many families was all they wanted to know,” said Mr Orde, who was chief constable from 2002 to 2009.

The civil costs of meeting claims for reparations from victims’ families now “seem uncontrollable”, but most money being paid over by the PSNI was going to lawyers, not the families, he said.

“This will financially cripple operational frontline policing in Northern Ireland,” he said, saying that it “soaks resources” away from dealing with today’s challenges.

Rejecting charges of collusion and improper conduct by officers during the Troubles “in all bar a few cases”, Mr Hamilton said today’s investigations did not consider that many investigations conducted during the three-decade conflict were flawed.

“It’s not so much that a lot of the investigative standards followed during the Troubles are way short of what we have today, but rather that every time a report comes out it’s almost like a shock and a surprise,” he said.

“The incompetence or poor investigative standards of yesteryear gets translated in some communities where there is a bit of a confidence deficit anyway in policing into collusion, into conspiracy.

“There will be a small number of cases where practice went on that shouldn’t have happened, but for the most part it was just substandard investigations.”