A team of researchers investigating a star’s dramatic dimming uncovered a cloud of dust and gas about 120 million miles (200 million kilometers) wide. Exactly what caused the cloud to form, and the nature of its host object, remain unknown.

From September 2024 to May 2025, a Sun-like star designated J0705+0612 became 40 times dimmer. Researchers describe the phenomenon in a study published today in The Astronomical Journal, identifying the culprit as a slowly orbiting giant cloud.

“Stars like the Sun don’t just stop shining for no reason,” Nadia Zakamska, a Johns Hopkins University professor of astrophysics and co-author of the study, said in a NOIRLab statement, “so dramatic dimming events like this are very rare.”

A pesky cloud

In this case, Zakamska and her colleagues integrated telescopic observations with the star’s archival data and concluded that a cloud of dust and gas had, for a while, obscured the star. According to their estimates, the distance between this feature and the star is about 1.2 billion miles (2 billion kilometers). The star is located 3,000 light-years from Earth.

Cue a mysterious third player: a gravitational tie seems to link the cloud to another body at the edge of J0705+0612’s planetary system. Researchers don’t yet know what this body is. It orbits J0705+0612 and needs to have enough mass to keep the cloud from coming apart. According to their findings, it must consist of a few Jupiter masses—at least. A very large exoplanet, a brown dwarf, or a very low-mass star are potential candidates.

If the body is a star, the cloud would be a circumsecondary disk—a frisbee of debris orbiting the less massive companion in a binary system. If it’s a planet, the cloud would be a circumplanetary disk. More broadly, it’s rare for researchers to observe a star being obscured directly by the disk of a secondary object.

What’s in the cloud?

“When I started observing the occultation with spectroscopy, I was hoping to unveil something about the chemical composition of the cloud, as no such measurements had been done before. But the result exceeded all my expectations,” says Zakamska.

The team found a number of metals in the cloud. To astronomers, metals are elements heavier than helium. They also directly recorded the gas’s three-dimensional movement, revealing a “dynamic environment with winds of gaseous metals,” such as calcium and iron, according to the statement.

J0705+0612 and the cloud are moving independently of each other, as revealed by the team’s measurements of the wind’s direction and speed. Combined with the length of the obscurement, this provides additional verification for the team’s theory that the thing doing the obscuring is another object’s disk orbiting in the periphery of J0705+0612’s stellar system.

“The sensitivity of GHOST allowed us to not only detect the gas in this cloud, but to actually measure how it is moving,” Zakamska said. GHOST (the Gemini High-resolution Optical SpecTrograph) is the instrument they used to study the makeup of the cloud. “That’s something we’ve never been able to do before in a system like this.”

How did it form?

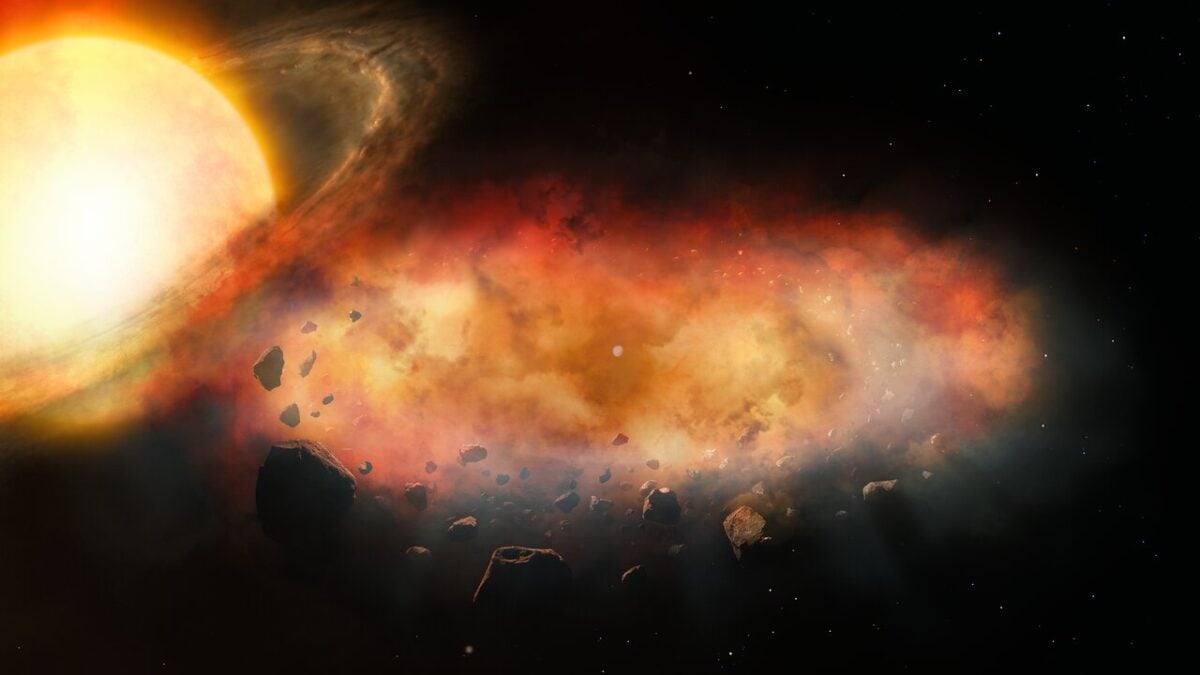

The team detected an infrared excess—an overabundance of infrared light—which typically signals the presence of a protoplanetary disk, the swirling debris around a young star where planets begin to form. However, J0705+0612 is by no means young. It’s over two billion years old, meaning it shouldn’t feature such a disk. As such, the cloud in question probably isn’t remnant material from when the star was younger and the system was producing planets.

As for how the disk came to be, two planets might have created the cloud by smashing into each other at the fringes of J0705+0612’s planetary system, spewing out debris, dust, and rocks, the researchers argue.

“This event shows us that even in mature planetary systems, dramatic, large-scale collisions can still occur,” Zakamska said. “It’s a vivid reminder that the Universe is far from static—it’s an ongoing story of creation, destruction, and transformation.”