Photo: Courtesy of Sundance Institute/All photos are copyrighted and may be used by press only for the purpose of news or editorial coverage of Sundance Institute programs. Photos must be accompanied by a credit to the photographer and/or ‘Courtesy of Sundance Institute.’ Unauthorized use, alteration, reproduction or sale of logos and/or photos is strictly prohibited.

It’s in the rules: Every comedian will get at least one major documentary dedicated to them before we’ve all departed this earth. And quite a few of them will have been directed, co-directed, or produced by Judd Apatow, who’s already given us Mel Brooks: The 99 Year Old Man, The Zen Diaries of Garry Shandling, and George Carlin’s American Dream. At first glance, the idea of Apatow making a film (alongside co-director Neil Berkeley) about Maria Bamford might not seem like a particularly noteworthy endeavor. Bamford, 55, is an active comedian still in the middle of an influential and admittedly offbeat career. Isn’t it too early to try and provide perspective and context on her life and work?

Well, maybe not. The peculiar charm of Paralyzed by Hope: The Maria Bamford Story, premiering at Sundance, lies in the way it’s driven by genuine curiosity about its subject. Apatow doesn’t seem to have come to this film with a thesis and a story and an outline already in hand. He’s perplexed and fascinated by Bamford, who exists in a strange category: She’s won awards and gained quite a bit of mainstream visibility and success (thanks to her many voice roles, her once-notorious Target ads, and her short-lived but well-loved Netflix show Lady Dynamite, along with seemingly a million other efforts), but her brand of humor is something of an acquired taste, built as it is on confessional discomfort. She foregrounds her mental challenges, her nervous breakdowns, her suicide attempts, her fraught relationships with her parents, all the things other comedians merely nod to. “Ninety-nine percent of comedians will tell you they have anxieties, and you understand it’s a shtick,” Conan O’Brien says in the film. “Maria is like a lobster whose shell has been removed.” As Bamford herself puts it while receiving a prescription for the tremors she gets from her mood stabilizers: “Weakness is the brand.”

In the world of comedy nerds, Bamford and her work are beyond well known. Those of us who haven’t been following her career may still find ourselves captivated by our first glimpse of her in this picture. Welcoming Apatow and his film crew into her home, she comes off as both aggressively cheerful and hopelessly fragile, as if she could have an immediate meltdown if she were to stop smiling. This is part of her persona. And while it seems like an act, it clearly isn’t; it’s when Bamford “acts normal” that she’s pretending, which she admits has led to some confusion and conflict throughout her life.

Watching her perform, we enter a universe where up is down and fake is real, and our disorientation makes her humor essential: She becomes our guide through this inside-out reality of hers. A lot of comedy documentaries have pro forma talking-head interviews with other comics opining on the supposed uniqueness and boldness of the subject matter. This time, we believe them. When Patton Oswalt says that he didn’t initially get Bamford’s humor, it makes sense, because at first her humor doesn’t seem like humor at all; it feels like a cry for help. But that’s also what makes it funny. Sort of. Maybe. Definitely.

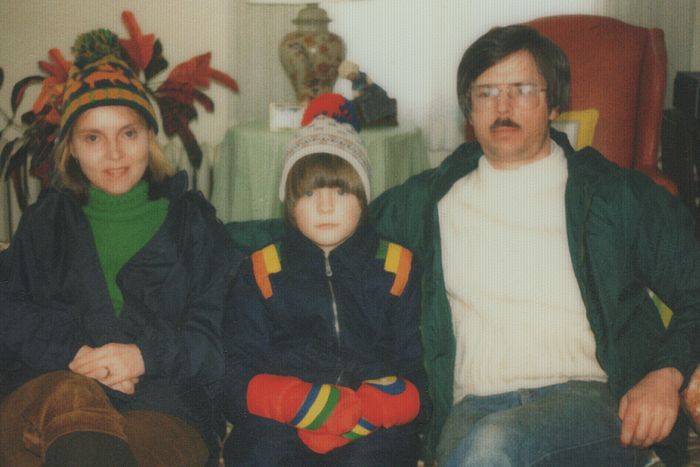

Itself awkwardly poppy in a manner that reflects Bamford’s own half-terrified merriment, Paralyzed by Hope charts the comedian’s early years with a particular focus on her tortured relationship with her mother, a regular subject of her act. Always on diets and mood stabilizers and prone to manic episodes during which she might try to call the Pope or run the family car off the road, Maria’s mother appears to have projected her own anxieties onto her daughter. But later in life, Mom also became a therapist and was fully supportive of Maria’s work, often appearing in bits playing herself. Theirs is a fraught, passionate, loving, and contentious bond; when Bamford’s mom dies during COVID lockdown, we feel the loss. But we also get it when Maria does one final weight-loss joke about her mother’s death and talks about spreading her ashes at the Nordstrom shoe department. These are bits grounded in lived experience. (As is the bit about Maria’s dad bringing her and her sister a box of now-useless dildos after their mother’s death — something that actually happened.)

Bamford talks about having a particular type of obsessive-compulsive disorder involving unwanted thoughts — impulsive, intrusive ideas that one cannot control and that, if allowed to spiral, can become harmful. It sounds like a terrible condition, but also maybe a relatable one — everybody has had an unwanted thought or two, and one can imagine the horror of not being able to stop them from coming. Bamford keeps it in check with therapy, meds, and work. But it’s also, perhaps, something of a superpower for a comedian to have, at least in small doses, allowing the mind to wander in unexplored and improper realms, which is at the root of their art. Watching Paralyzed by Hope, we start to understand why other comedians, including Apatow himself, would be so fascinated and electrified by Bamford’s work. She lives on the front lines of a war others only occasionally allow themselves to fight.

Sign up for The Critics

A weekly dispatch on the cultural discourse, for subscribers only.

Vox Media, LLC Terms and Privacy Notice