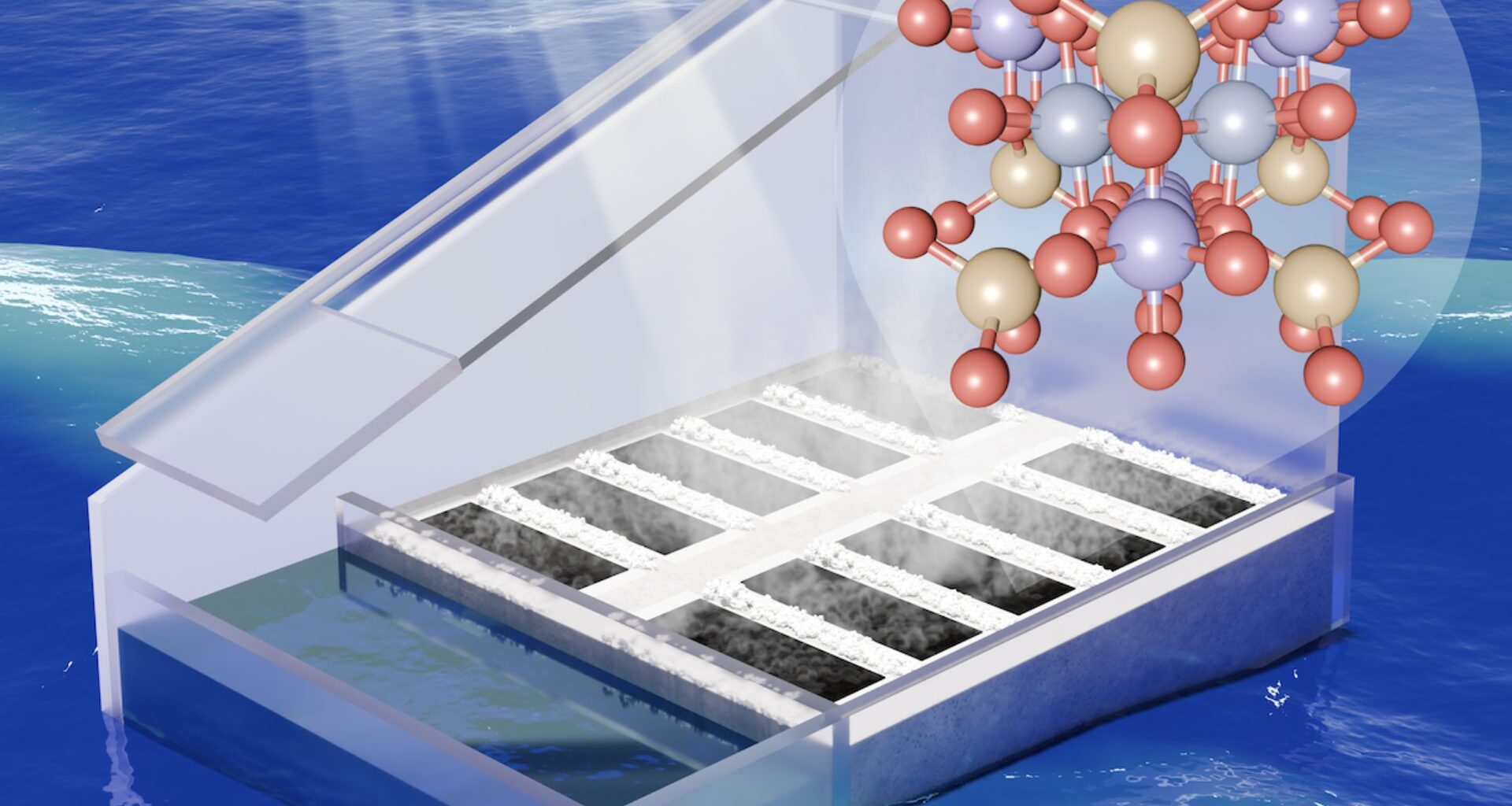

Scientists at the Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology (UNIST) in Korea have developed the world’s fastest oxide-based evaporator that can convert seawater into drinking water without electricity. The ternary-oxide-based evaporator uses sunlight as its power source, with a photothermal material at its core.

Desalinated seawater can be a valuable source of fresh water for remote island communities without access to central water supplies. However, desalinating water is an energy-intensive exercise. To overcome this hurdle, scientists have been developing solar-powered desalination systems that can operate in areas without access to electricity.

This can also be helpful in developing countries where access to clean water can be a problem. By using solar power, the design allows the evaporator to be used anywhere. However, the process can also be time-consuming, limited it adoption.

A team of researchers led by Ji-Hyun Jang, a professor at the School of Energy and Chemical Engineering at UNIST, addressed this by building the world’s fastest evaporator.

How does it work?

Central to this design is a new photothermal material, one that can absorb sunlight and convert it into heat. The researchers coated the evaporator’s surface with this thermal material, thereby enhancing its ability to evaporate seawater.

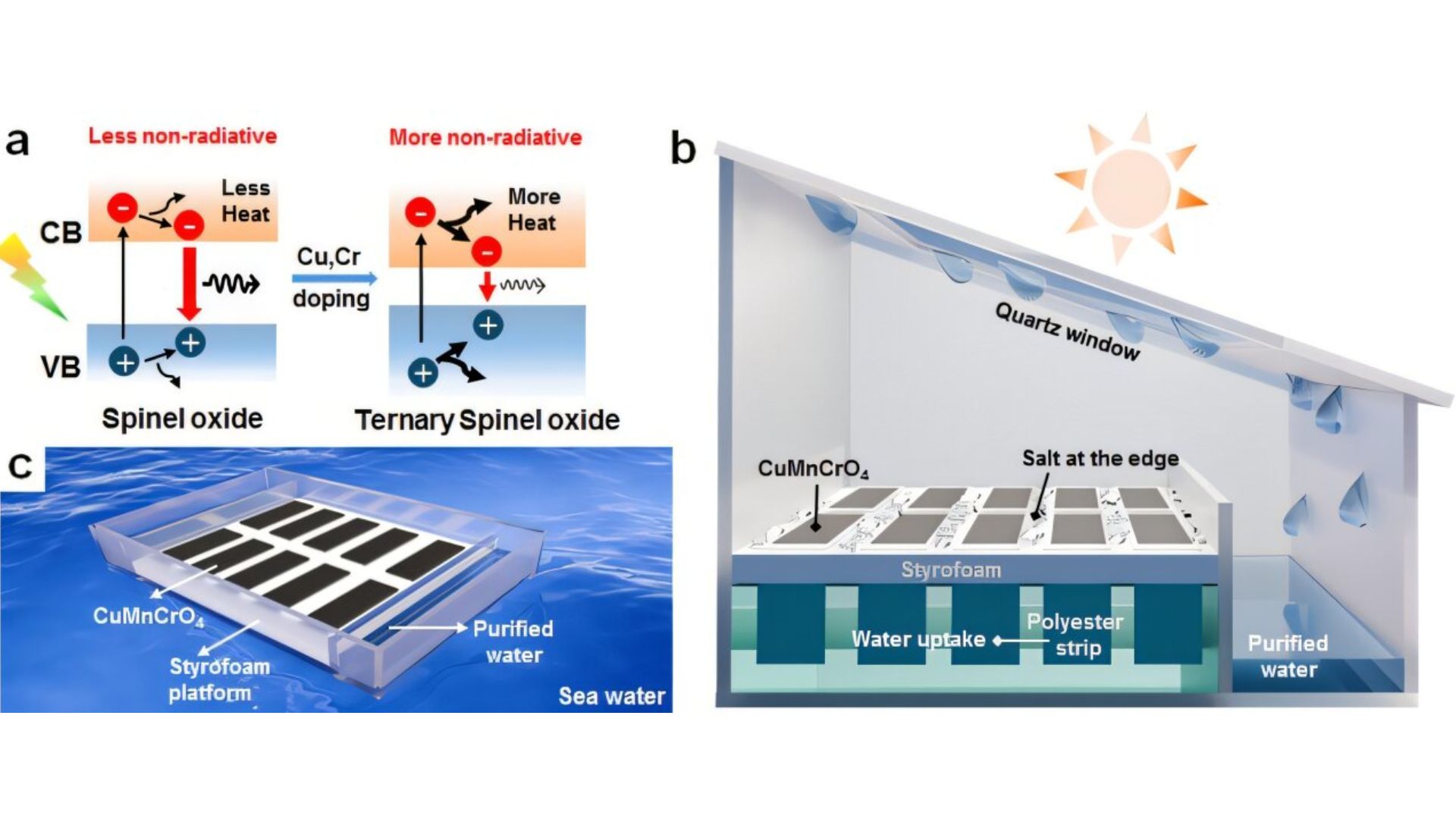

The material, a ternary oxide, was developed by replacing parts of manganese in corrosion-resistant manganese oxide with copper and chromium. Using bandgap engineering, the researchers were able to adjust the material’s absorbing capabilities across the solar spectrum.

While typical oxide materials absorb only visible light, this material can absorb almost 97 percent of the sunlight from ultraviolet to near-infrared. The result of this high-spectrum absorption is greater heat production with surface temperatures reaching 176 degrees Fahrenheit (80 degrees Celsius).

This is significantly higher than 165 degrees Fahrenheit (74 degrees Celsius), possible with copper-manganese oxides alone.

a) Schematic illustration of photogenerated charges and recombination processes in normal spinel oxide and ternary spinel oxide. b) Schematic description of solar evaporation system and c) Scalable floating device for seawater purification. Credit: Advanced Materials (2025). DOI: 10.1002/adma.202517285.

a) Schematic illustration of photogenerated charges and recombination processes in normal spinel oxide and ternary spinel oxide. b) Schematic description of solar evaporation system and c) Scalable floating device for seawater purification. Credit: Advanced Materials (2025). DOI: 10.1002/adma.202517285.

Preventing salt buildup

Although the photothermal material helped researchers increase the evaporation rate of seawater by as much as seven times compared to the natural process, they still needed to contend with the salt remaining on the surface after the water had evaporated.

This is a major problem seen in most solar desalination plants, irrespective of their evaporation rates. To avoid this, the researchers used an inverted U-shaped design with the photothermal coating on the part that absorbs water.

It also includes a water-wicking fiber material and a hydrophobic polyester fabric, which help draw water while allowing salt ions to flow away. This avoid build up of salt on the surface.

In their experimental setup, the researchers demonstrated that a 1-square-meter evaporator can produce about 1.4 gallons (4.1 liters) of pure drinking water per hour.

“We have fundamentally improved the light absorption range and the photothermal efficiency of oxide materials, which allowed us to develop a high-performance, durable evaporator,” said Professor Jang in a press release.

“Its scalability and stability mean it could be a practical solution to real-world water shortages.”

The research findings were published in the journal Advanced Materials.