Pushing quantum mechanics into new territory, recent research is showing that objects far larger than individual atoms can still exist in multiple states at once.

The experiments, undertaken by researchers from the University of Vienna and the University of Duisburg-Essen, demonstrated that massive nanoparticles, composed of thousands of sodium atoms each, obeyed the rules of quantum mechanics despite their large size and the relatively great distance between them.

The researchers behind the recent work published their findings in a recent paper that appeared in the journal Nature.

Quantum Mechanics

In the often strange world of quantum mechanics, light and matter can behave as both particles and waves, as demonstrated in experiments such as the double-slit experiment. At larger scales, however, we do not observe this behavior in everyday objects, such as a marble, which follows a predictable trajectory and has a well-defined location, consistent with the rules of classical physics.

The new research demonstrates for the first time that the wave nature of matter persists even at large scales, using massive metallic nanoparticles each about the size of a modern transistor. The particles measured about 8 nanometers across and had a mass exceeding 170,000 atomic mass units, yet they still displayed quantum interference.

“Intuitively, one would expect such a large lump of metal to behave like a classical particle,” said lead author and doctoral student Sebastian Pedalino. “The fact that it still interferes shows that quantum mechanics is valid even on this scale and does not require alternative models.”

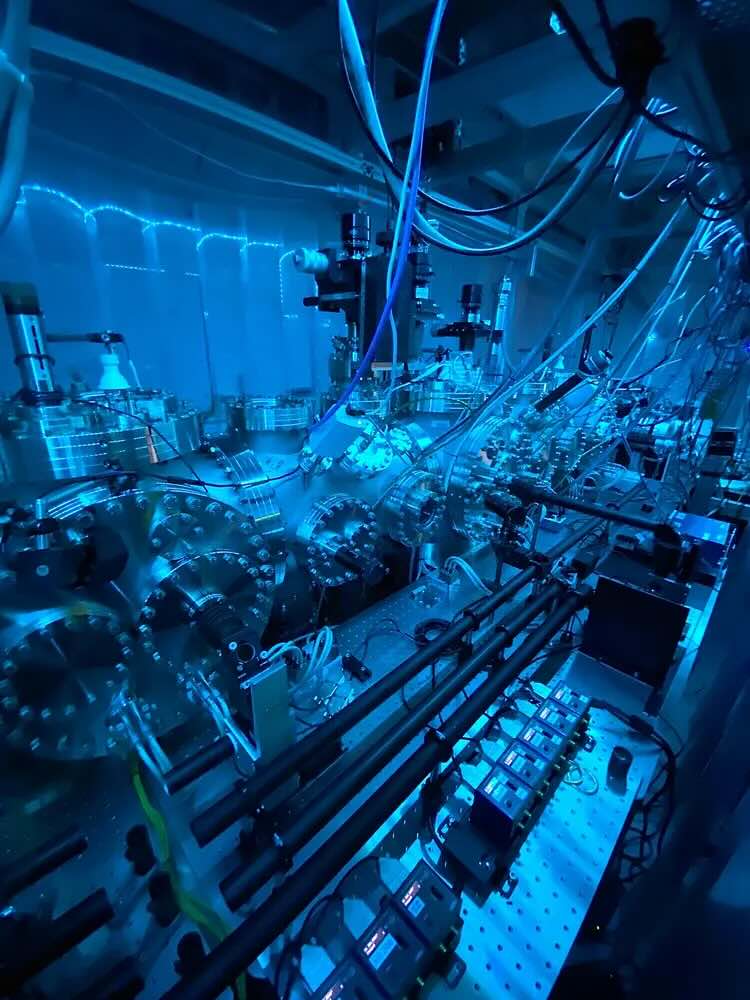

For their experiment, the researchers created cold sodium clusters, each containing between 5,000 and 10,000 atoms. The team then sent these clusters through three ultraviolet laser diffraction gratings. The first laser beam placed the particles into a superposition of paths as they moved through the apparatus. At the end of the setup, those possibilities recombined to produce a measurable striped pattern of metal, consistent with quantum theory.

Schrödinger’s Quantum Particle

Physicist Erwin Schrödinger is famous for his 1935 thought experiment known as Schrödinger’s cat. In the scenario, a cat is placed in a sealed box along with a container of poison whose release is tied to the random radioactive decay of an element.

The experiment illustrates that, in quantum mechanics, because the release of the poison depends on a random quantum event, it cannot be determined whether the cat is alive or dead without opening the box and observing it. Until observation occurs, the cat is considered to be in both states simultaneously.

The new experiments show something similar: during their unobserved flight, the particles’ locations are not fixed, and their displacement spans distances many times larger than the particles themselves. Similar to the cat being both alive and dead, the particles exist in a superposition of positions rather than occupying a single fixed point in space.

Macroscopicity Measured

Klaus Hornberger, one of the study’s co-authors, has been working on a comprehensive theory of near-field interferometry for the past 20 years. In pursuit of that goal, he, along with co-author Stefan Nimmrichter, developed a measurement they call macroscopicity, designed to make different kinds of quantum experiments more directly comparable. The metric compares experimental results to existing quantum theory, quantifying how much real-world observations deviate from theoretical expectations.

For this most recent experiment, the team measured a macroscopicity of μ = 15.5. This result is an order of magnitude greater than any other experiment the team is aware of. On the smaller scale of electrons, an equally rigorous test would have to run for about 100 million years, whereas their macro-scale test required only one hundredth of a second.

Going forward, researchers plan to continue pushing these macro-scale experiments into even larger systems and other materials to investigate how quantum effects may influence the world at more familiar scales. The team is hopeful that technological advances will enable orders-of-magnitude improvements in precision for future macroscopic measurements.

The paper, “Probing Quantum Mechanics with Nanoparticle Matter-wave Interferometry,” appeared in Nature on January 21, 2026.

Ryan Whalen covers science and technology for The Debrief. He holds an MA in History and a Master of Library and Information Science with a certificate in Data Science. He can be contacted at ryan@thedebrief.org, and follow him on Twitter @mdntwvlf.