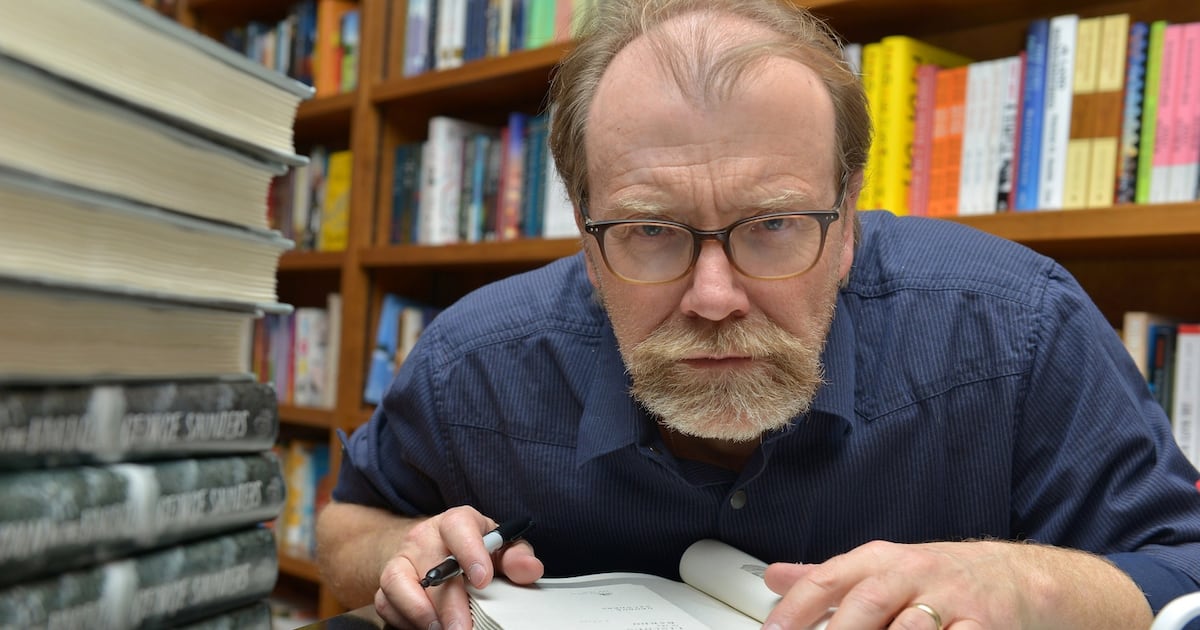

“I’ve discovered the two different sides to my personality,” George Saunders says. He’s talking to me from his home in Santa Monica, California, about his new novel, Vigil. Normally, he loves doing this sort of thing, but “this time it’s been complicated, because I’ve an elderly dog downstairs who is sick, my dad is in hospital and my wife’s back went out.”

So he’s discovered both his “ambitious, driving side, and I also have a nurturing side, and they’re both having to be invoked at once”. As a result, “I’m a little tired.” But as it happens, these two sides – looking after number one, and empathy for others – are at the heart of Vigil, which comes nine years after Saunders won the Booker Prize for his debut novel, Lincoln in the Bardo.

Anyone familiar with Saunders’s work – either Lincoln or his several books of tragicomic short stories that preceded it – will know to expect something unusual, and he doesn’t disappoint. Vigil is narrated by a 22-year-old woman called Jill “Doll” Blaine – who is dead. Jill is now a spirit who descends on dying people, to provide comfort to them as their life ends. She’s done it 342 times before, so she’s pretty experienced.

But this time it’s different. Her target, whom she’s charged with comforting, is a bad guy. KJ Boone, an eightysomething oil baron, during his prime was at the forefront of distorting climate data and persuading people and politicians that fossil fuels were just fine to keep using – and he has no regrets.

“There was a run where Biden was president and there were four or five horrific weather catastrophes in the news one after another,” says Saunders. “And I thought, if there are climate sceptics, which apparently there are, what do they make of that? I thought of someone who was intimately involved in that whole denial movement. Could he rise to the occasion and cop to it, or would he be locked in denial?”

With a work of art, you kind of come up this hill and what’s happening is increased ambiguity, maybe a little confusion, less judgment

So is that Saunders’s idea of the worst thing morally that a person can be these days? “Not really. I thought it was pretty bad. I mean, we’re finding out that there are worse places to be, even now, as we speak. He’s not Stalin, but the consequences of what he did, him and his ilk, are enormous.”

But also, he chose this character “partly because I have history in the oil business”. Saunders was a relatively late starter as a writer, publishing his first book in 1996 at the age of 38. His background was in engineering and industry. “I could see a world where I might have become him.”

Boone, then, is a morally reprehensible character. But aren’t they the most fun to write? “It was a lot of fun to be him,” agrees Saunders. “It was fun to be him when he was being rude.” Boone insults Jill, who after all is only trying to comfort a dying man. And it’s fun to read, too, especially as other characters from Boone’s past come along and argue with him. The pages turn quickly, which belies the painstaking process of writing.

“This book, I tried to read it [through] twice a week, from the beginning. When you do that, sometimes these improvements present [themselves], and you just do them. If you look at the first version and the last one, there’s a lot of differences, but it’s incremental.”

When we’re getting our asses kicked by life, it does feel to me that that’s probably the closest to the truth we ever get

— Saunders

The question at the heart of Vigil is whether anyone is beyond helping or saving. Halfway through the book Jill, thinking back to her own young death, and the man who accidentally killed her, thinks, “You cannot free him. But you might comfort him.” The idea runs through the book that being comforted in extremis (“for all else is futility”) is a high ideal that everyone – even the bad guys – deserves. Is that Saunders’s view too?

“It was at the outset. And then as I was writing it, I started to see little holes in [Jill’s] argument.” But Saunders – who, along with his wife, is a Buddhist – is uncomfortable with the idea of blanket condemnation or finger-pointing.

“We have this thing going on with the dog at the minute, and it’s very emotional. I’m totally overwhelmed. And when we’re challenged, when we’re getting our asses kicked by life, it does feel to me that that’s probably the closest to the truth we ever get. When I’ve been down like that, I don’t feel like blaming anybody. I just feel a little sad and open and kind of like, ‘Yeah, it’s tough down here, brother,’ you know?”

“So in that case I agree with [Jill], but one of the adventures of this book was to [have] a series of moments where different characters get to step up to the microphone, and not to try to signal to the reader that I don’t believe this or I do believe that.”

For example, Jill’s opposing side on the question of comforting the unrepentant oil man is the spirit of an unnamed French man, who has no time for such soft ways. “Any comfort you give him,” he tells Jill, “will only serve to confirm him in his current state of delusion. You let him off the hook.”

On this, Saunders says, “The discovery of the book was that I thought I was a 100 per cent Jill fan, and that the French man was just annoying. And then over the course of revising the book, I thought, oh, you guys both have a point.”

Presenting alternative viewpoints is all very well, but Jill remains the voice of the novel, so her views take precedence in the reader’s mind, even if Saunders didn’t intend it that way. Still, the characters who come and have their say at Boone are entertaining: there are shades of Lincoln in the Bardo in the range of voices and fast-paced dialogue.

And anyway, perhaps the very act of reading a book – this book, any book – can help us become more understanding, more like Jill. Howard Jacobson, another Booker winner, used to suggest optimistically that if everyone read Middlemarch, the world would be a better and more understanding place.

Saunders seems to agree. “We [all] have our political opinions and our alignments and it’s all very simple and emotional and agitated. And then with a work of art, you kind of come up this hill and what’s happening is increased ambiguity, maybe a little confusion, less judgment. And at the top of that hill, you have a couple of moments of maybe seeing what it would be like to live up there. And the reason we like that is because we see that we have a higher capacity for love or compassion than we think.

“Then, of course, you come back down the other side of the hill and you’re a regular old ass again.” He laughs. “But that for me is what art has always done, is give you a couple of minutes at the top of the mountain.”

And this ties in with Saunders’s 2013 commencement speech at Syracuse University, titled “Congratulations, by the way”, where he espoused the necessity of kindness. But, I say, we don’t always want to offer compassion or empathy. For example, I like hating Donald Trump. I’ve put a lot of work into it, I’ve got pretty good at it and I don’t really want to give it up. There’s a certain pleasure in hating those we think are bad, isn’t there?

US vice-president JD Vance and US president Donald Trump during a meeting with oil and gas executives at the White House. Photograph: Alex Wong/Getty

US vice-president JD Vance and US president Donald Trump during a meeting with oil and gas executives at the White House. Photograph: Alex Wong/Getty

“There is. And also there’s something powerful about it. But I think people can certainly convert the rage into something. The question is, is it useful? That’s on my mind because I can rage against Trump all day long. [But] is it helping? For me personally, if I take the rage down and try to understand the world from inside their point of view – which I admit is very, very difficult with this gang – the reason to do that is not to be saintly, but to increase your effectiveness.

[ George Saunders on Lincoln, Trump and impressing his wifeOpens in new window ]

“But,” he adds, “I’m also with you because it’s a very enraging time and one of the things I see in the left wing is an ultra-polite, cautious approach, and I don’t think those people are going to be slowed down by that. They believe in power for power’s sake. And it takes a really creative approach to beat that.”

Of course, the internet with its algorithms and echo chambers doesn’t help us see things from other viewpoints, does it? “I think they make things 10 times worse, because whatever brain fart you have, you google it and then it confirms your brain fart is real. It’s like we’ve got a prosthetic projection machine. We do a lot of projecting ourselves, and then the internet taps in and authorises whatever projection you’re having at the moment.”

Was it hard for him to write novels after so many years of short stories – and very densely written, often eccentric stories at that? “Yeah, and I still don’t think I know how to. In a funny way, I don’t consider myself a proper novelist at all. I don’t know how to do the 400-page, multi-character [book].”

Yet his novels and stories have something in common. Because they’re unusual, and readers have to invest more of themselves in the story, we tend to feel them more personally – which explains why Saunders’s readership has grown and grown, as readers recommend him to others.

“I think you’re right. Early on, I had to give up on a more traditional fictive stance and try to do something a little more like stand-up, or whispering something urgently to someone at a train station with a very high level of frankness.” He adds, “The highest thing I would love to do [as a writer] is to get into you personally and have you go … ‘Amen, brother. That’s it’.”

Vigil is published by Bloomsbury on January 27th