Credit: Meletios Verras/Getty Images

Credit: Meletios Verras/Getty Images

Last year’s landmark case of “Baby KJ”—the first patient to receive a personalized CRISPR‑based gene therapy—showcased both the promise and the persistent challenges of genome editing. While CRISPR systems can act as remarkably precise molecular scissors, their active enzymes don’t always switch off cleanly. Lingering Cas activity can nick unintended DNA or RNA targets, raising the risk of harmful mutations in healthy genes. For CRISPR to reach its full therapeutic potential, researchers need reliable ways to keep these editors in check.

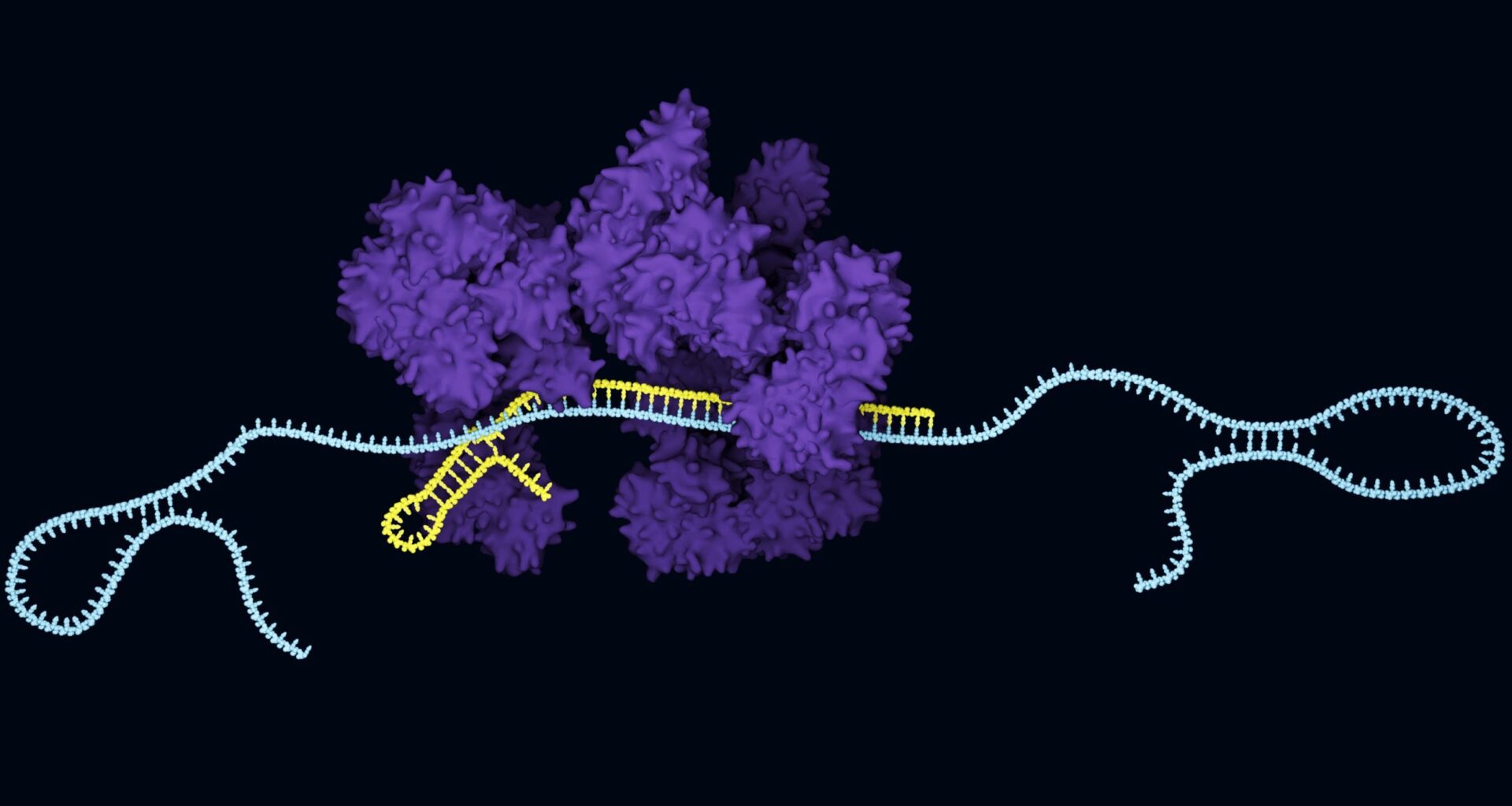

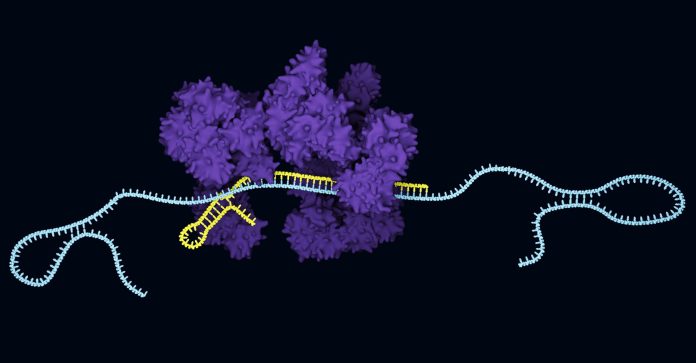

That’s where anti‑CRISPRs come in. These phage‑derived proteins act as natural off‑switches for CRISPR–Cas systems, blocking nuclease activity through mechanisms ranging from competitive inhibition to disruption of effector complex formation. But despite their utility, anti‑CRISPRs (Acrs) are notoriously difficult to find. In the past decade, only 118 experimentally validated Acrs have been identified—an effort that could be compared to playing molecular “Where’s Waldo.”

A team of researchers from Monash University and the University of Melbourne believes AI can change that. In a new study published in Nature Chemical Biology, titled “De novo design of potent CRISPR–Cas13 inhibitors,” the group describes a rapid, AI‑accelerated strategy for designing entirely new anti‑CRISPR proteins. “We leveraged de novo protein design to create new‑to‑nature protein inhibitors of CRISPR–Cas, which we call artificial intelligence (AI)-designed Acrs (AIcrs),” the authors wrote.

The team focused on Cas13a from Leptotrichia buccalis, an RNA‑targeting CRISPR effector for which no validated natural inhibitors exist. Using RoseTTAFold‑Diffusion (RFdiffusion) for protein generation and ProteinMPNN for inverse folding, the researchers computationally designed candidate inhibitors capable of binding and blocking Cas13a. They then validated these designs across a comprehensive workflow in both bacterial and human cells.

According to lead protein designer Cyntia Taveneau, PhD, “Using AI‑accelerated protein design, we rapidly produced functional inhibitors of CRISPR that function in bacterial and human cells.” The entire process—from target selection to hit and lead identification—took just eight weeks, a dramatic acceleration compared to traditional discovery‑based approaches.

The speed matters because natural Acr discovery remains slow and unpredictable. “The discovery of natural inhibitors against clinically relevant targets remains challenging and time‑consuming,” noted co‑author Rhys Grinter, PhD. By contrast, the AI‑designed inhibitors demonstrated potent and specific suppression of Cas13a nuclease activity, functioning through mechanisms consistent with their computational design.

Anti‑CRISPRs typically inhibit CRISPR–Cas systems by blocking crRNA or target nucleic acid binding, or preventing formation of the active effector complex. The AI‑designed Acrs appear to follow similar principles, but with the advantage of being engineered for a specific Cas target.

Associate professor Gavin Knott, PhD, sees broad implications for the field. The ability to “design bespoke inhibitors that can keep CRISPR ‘in line’ will contribute to the ongoing development of CRISPR tools in diverse applications across research, medicine, agriculture, and microbiology,” he said.

While these AI‑designed inhibitors are still early‑stage, the work demonstrates a powerful new route for expanding the CRISPR control toolbox. If CRISPR is to become a reliable therapeutic platform, precise and programmable off‑switches may be just as important as the editors themselves—and AI may be the key to building them on demand.