The “Too Few, Too Bright” Bias

One of the models developed by the research team is the sophisticated AM4-MG2 model, which applied the two-moment Morrison-Gettelman cloud microphysical parameterization with prognostic precipitation (MG2) to the existing Atmosphere Model version 4.0 (AM4.0). This improved on the previously-used AM4.0 by applying a scheme that included the detailed microphysical processes that determine how clouds form.

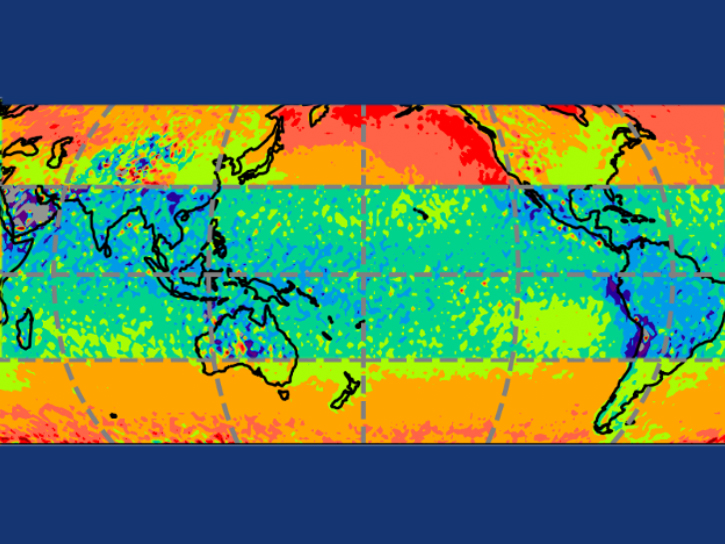

While AM4.0 and AM4-MG2 are very similar – they have the same dynamics, radiation, and convection schemes – they have different methods of predicting cloud properties at the microscale. The research team compared their AM4.0 and AM4-MG2 atmospheric models with observations based on simulations from five satellite instruments — the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS), International Satellite Cloud Climatology Project (ISCCP), The Cloud-Aerosol Lidar and Infrared Pathfinder Satellite Observation (CALIPSO), Multi-Angle Imaging SpectroRadiometer (MISR), and CloudSat — spanning from 2000 to 2020.

NASA Distributed Active Archive Centers like the Level-1 and Atmosphere Archive and Distribution System (LAADS DAAC) provide datasets for these instruments that are tailor-made for comparison to model satellite simulators, such as the Level 3 Cloud Feedback Model Intercomparison Project (CFMIP) Observation Simulator Package (COSP) cloud properties suite of satellite data products for MODIS. What they discovered supported an already widely-accepted bias: the models produce far fewer clouds than satellites observe, and the clouds the models created were much brighter and more reflective than real observations.

“Clouds play an important role. You’ve probably seen this from a plane, when you look down at the tops of clouds, it’s really, really bright,” says Kramer. “To increase the amount of reflection out to space from the Earth, you can add more clouds, or you can make the clouds brighter. The goal is to make sure the amount of total energy being reflected out to space by the clouds in the model is correct. What we find is we’re getting the total reflection pretty accurate, but for the wrong reasons. We don’t have enough clouds, which is less reflection. And the clouds the models do have are too bright, which is more reflection. Essentially these biases cancel out. We get the overall energy balance, but to some extent for the wrong reasons.”

Specifically, the models underestimated low-level cloud coverage, like marine stratocumulus clouds, by more than 10% globally. These clouds form over oceans near continental coastlines and play a crucial role in Earth’s energy balance by reflecting sunlight back to space.

The newer AM4-MG2 model showed improvements over its predecessor AM4.0, better representing these important cloud systems along the western coasts of continents. This enhancement comes from more sophisticated mathematical representations of the physical processes within clouds. However, when cloud coverage exceeds 20%, the simulated clouds reflect substantially more solar radiation than satellites observe in nature.