MIT Media Lab has developed a prototype that uses generative AI to interpret and distil the contents of a photograph into a fragrance.

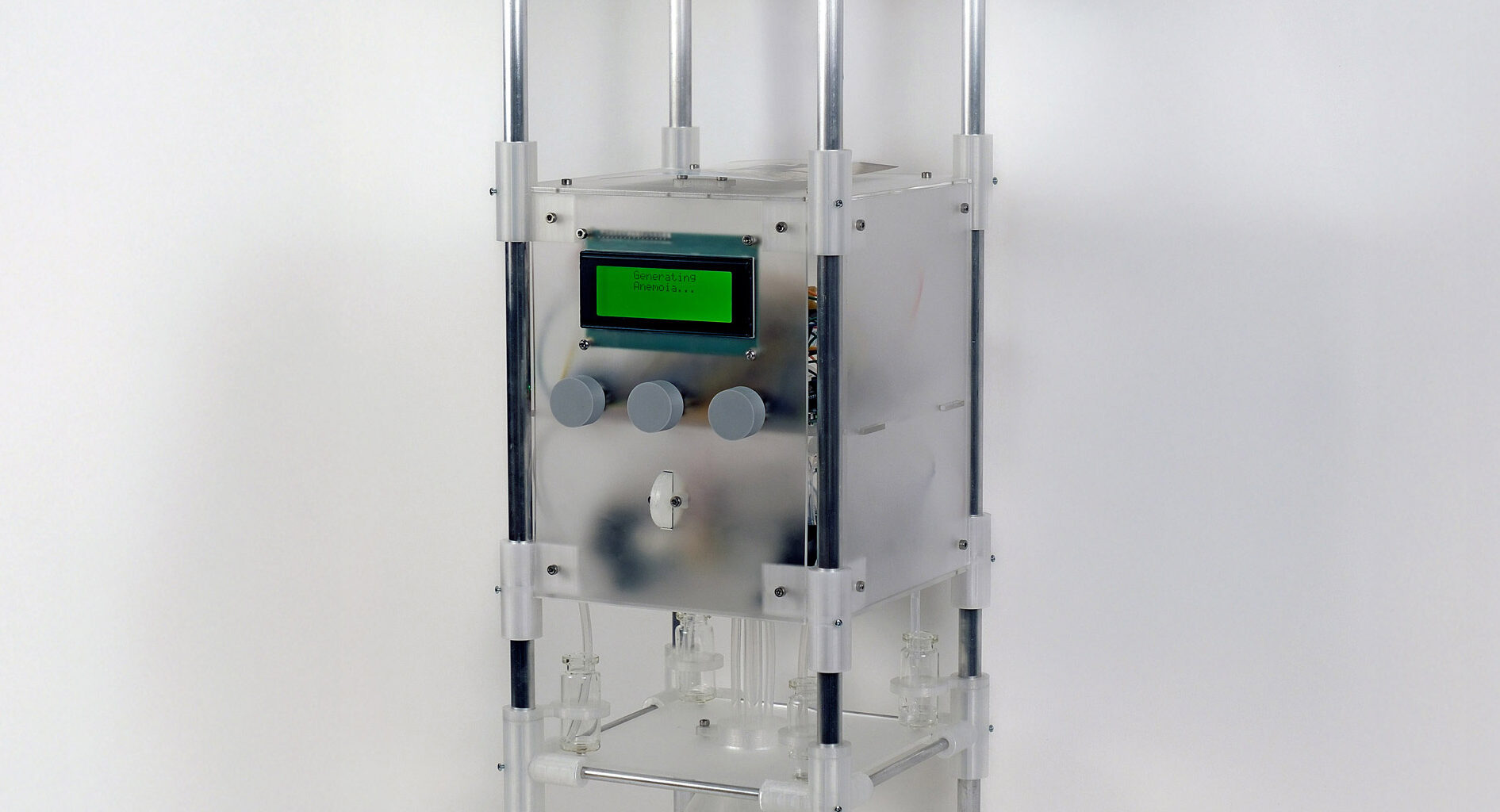

The Anemoia Device, referred to as “scent-memory machine” according to MIT, consists of three parts arranged vertically: users place an analogue photograph in the top section.

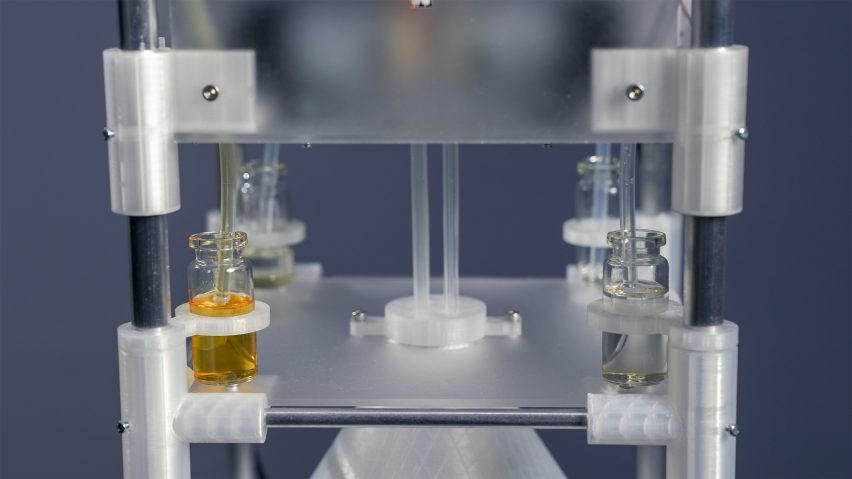

An AI-powered computer, located in the middle, analyses the image and allows the users to craft a prompt using three dials. Then, the machine produces a custom scent from a set of pumps connected to fragrance reservoirs at the bottom.

Cyrus Clarke of MIT Media Lab has created a prototype that converts photos and inputs into scents

Cyrus Clarke of MIT Media Lab has created a prototype that converts photos and inputs into scents

“The whole pipeline is built around a metaphor of distillation where you take a dense, layered memory artefact and transform it and compress it into something,” said Cyrus Clarke, the MIT researcher who developed the machine.

With the Anemoia Device, Clarke is taking an interest in a particular branch of nostalgia called “anemoia,” which can be described as nostalgia for a time you’ve never experienced.

The Anemoia Device can supposedly turn any photographic memory into a scent, but Clarke was particularly interested in unlived memories.

Users scan an image and then work through prompts to end up with a custom fragrance

Users scan an image and then work through prompts to end up with a custom fragrance

“Childhood photographs, family archives, inherited recipes are the obvious destinations,” he told Dezeen, but “the anemoia framing lets the system start in a broader, more universal space, and then move toward the harder and more personal question territory.”

The machine uses a vision-language model to interpret the content of an image, but users can influence the final output by interacting with the dials.

First, they select a particular point of view from the photograph. This could be a human being depicted in the photograph, or it could be a non-living object, like a tree or a bicycle.

Kitchen Cosmo is a “playful and intentional” AI appliance that generates recipes based on leftovers

Then, if the subject is a person, they can specify if they are a child or an elderly person. If the subject is an object, they can situate it in its lifecycle with options like “raw” to “in-use”, or “decay”.

Finally, they can assign an emotional tone to the photograph, and therefore to the scent, by choosing between emotion words.

During a trial session, Clarke recalled one participant who uploaded an archival photograph of a couple eating what appeared to be an apple or a pear, on stone steps, in a beautiful garden. The user specified the fruit as the subject, selected “in use”, and chose “calm” as the mood.

The resulting scent formulation had a hint of spiced apple, pear, and an earthy musk.

“The user smelled the output and initially described being transported to autumn, which made sense as a major component of the scent,” said Clarke.

The prompts are driven by an AI

The prompts are driven by an AI

Clark is aware that there is more to a moment in time than the obvious associations a machine might make between “apples” and “autumn”.

He said this “shared vocabulary” was important to help the system land somewhere before it could get more nuanced and creative. But that doesn’t mean the machine falls into clichés every time.

For one, the current prototype includes a scent library of 50 fragrances ranging from sandalwood and pine forest to old books, leather, and sand.

Each of them is delivered in “one-second” increments, which ultimately creates a wide variety of mixtures that are highly dependent on the user prompt.

Dials allow users to select from options after the photograph has been interpreted by the machine

Dials allow users to select from options after the photograph has been interpreted by the machine

Clarke explained that the narrative that users build around the photograph can also circumvent literal translations.

“Two people can turn the same beach photo into very different atmospheres based on their selections,” he said.

MIT and Harvard researchers find secret to “self-healing” Roman concrete

Clarke has long been interested in ways to make memories more tangible. Before MIT, he explored how memories could be stored in the DNA of plants through a research organisation he founded, called Grow Your Own Cloud.

“In today’s reality, our memories are externalised, usually stored in digital infrastructure and retrieved through functions, files, and feeds,” he told Dezeen. “They’re accessible, but they’re not truly with us, and I want to change that.”

Ultimately, he envisions two ways to develop his prototype further. One is a desktop-sized device that people could use to “print” memories at home. Another is an online service that would allow people to send in their photos remotely.

It mixes from a library of 50 scents

It mixes from a library of 50 scents

“I’m aware of the contradiction of using technology to reconnect us to the senses and even nature, but I embrace that,” he said.

“I don’t think everything has to be an attention-stealing machine, and I do think we can and should create new forms of computing that make you pause, breathe, and notice the world again.”

Other forays into designing for scent include a diffuser that uses recyclable cellulose scent “cards”.

The images are courtesy of MIT.