Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it’s investigating the financials of Elon Musk’s pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, ‘The A Word’, which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Read more

Fourteen years after she first clicked “publish” on a recipe blog, Ella Mills has a confession to make: the wellness industry she helped popularise no longer resembles the one she entered.

What began as a joyful push to get people cooking more vegetables has hardened into something louder, pricier and, in her view, far less effective.

“Wellness just wasn’t something that existed in the ether around us,” she tells Emilie Lavinia on The Independent’s Well Enough podcast, recalling the early days of Instagram, spiralised courgettes and the novelty of almond butter. “And now it’s a multi-trillion dollar industry.”

The problem, Mills argues, isn’t that people care about health. It’s that modern wellness has become so overcomplicated that it’s actively pushing people away from the basics.

There are pluses and minuses to that evolution, she acknowledges. But as wellness has grown, so too has the pressure: pressure to buy gadgets, powders and supplements; pressure to follow increasingly dogmatic rules; pressure to optimise every corner of daily life. “We’re letting go of the basics,” she says. The result? “I don’t think the wellness industry is working.”

That’s not a claim designed to provoke for provocation’s sake. It’s rooted in the data Mills keeps returning to: we eat fewer vegetables than at any point in the last 50 years; more than half of our calories now come from ultra-processed foods; most of us aren’t getting anywhere near enough fibre.

“Our foundations, when it comes to food, are really struggling,” she says. “This shouting at each other about whether you’re following X, Y or Z diet is incredibly frustrating.”

For Mills, the contradiction is glaring. “I don’t think you can have a multi-trillion dollar industry that’s grown at that speed when we’re collectively getting more ill and say the wellness industry is a wild success,” she says. “It’s making a lot of money. I’m not really sure it’s making enough people more, well.”

When Mills started Deliciously Ella in 2021, wellness felt inherently optimistic. “It was exciting,” she says, recalling the novelty of roasting lentils until crispy or blending spinach into smoothies. “It was people saying, ‘Have you ever tried this?’” Social media, then, was about encouragement rather than correction.

Fast forward to 2026, and the tone has shifted. “It’s wildly nuanced, very dogmatic,” she says. “Lots of people shouting at each other from different corners of the internet, making vast sums of money from products that do absolutely nothing.” Wellness has become something to buy, rather than something to practise.

That shift has consequences. With every scroll comes a contradiction: one day, oat milk is virtuous, the next it’s villainous. One week, seed oils are toxic, the next they’re misunderstood.

“Every single time you open your podcast app or Netflix or various media outlets, you’re going to see everything contradicting each other,” Mills says. “And it becomes so overwhelming that there’s almost a sense of, ‘What’s the point?’”

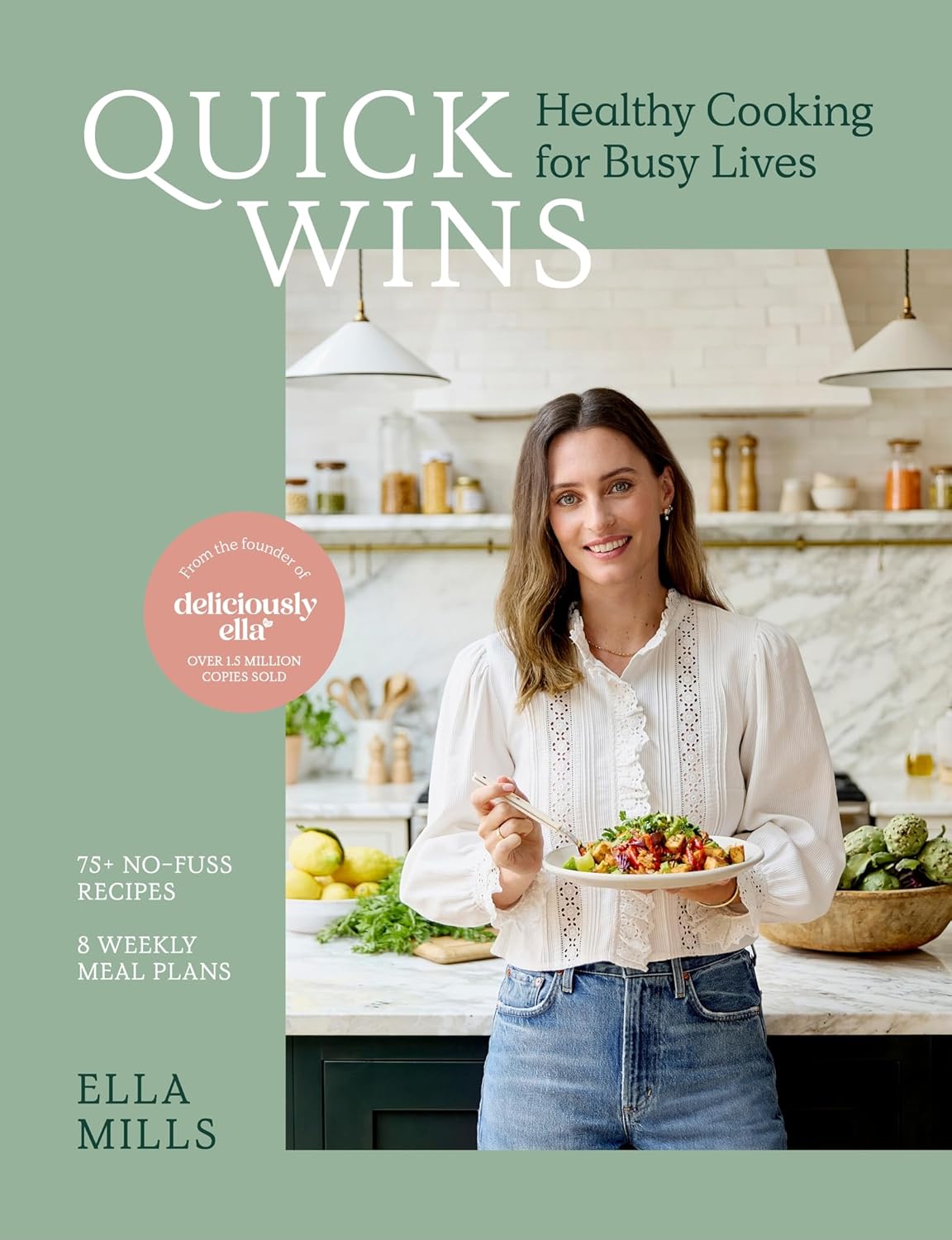

open image in gallery

‘Wellness has become something to buy, not something to practise,’ says Mills, who believes modern health culture is making us busier – not better (Supplied)

This matters because the stakes are high. Fear-based headlines about chronic disease collide with an already anxious world. “You kind of look at this and think, ‘What on earth am I meant to do? This will kill me, that will kill me, the next thing will kill me. It just becomes mad.”

For Mills, the tragedy is that wellness has drifted away from the very behaviours that most reliably support long-term health. “It needs to feel more approachable, more inclusive, more straightforward,” she says. “This is how you eat some more broccoli in a delicious way, and less, ‘You’re doing it all wrong’.”

That philosophy underpins Mills’ approach to New Year’s resolutions, and why she believes most of them fail. “Health isn’t a six-week bikini plan,” she says. “Health is genuinely supporting your mind and body so you get the most from your life for decades to come.”

The problem, she argues, is that humans are wired to overreach. “We really overestimate what we’re going to achieve today or next week,” she says, “and we wildly underestimate what we’re going to do in a year or two years.” Grand promises – cutting out sugar, exercising every day, overhauling an entire diet overnight – crumble the moment stress or fatigue enters the picture.

Instead, Mills advocates for what she calls “gentle habits”: small, repeatable actions that don’t demand willpower. “Eating super well this week will not do anything for your long-term health,” she says. “But small things every single day, for decades, will do enormous things for your health.”

That might mean adding one extra portion of plants a day. It might mean stirring lentils into a familiar bolognese, throwing raspberries into porridge or batch-cooking once a week. “It’s that idea of 1 per cent closer to your goal every day,” she says. “It sounds like nothing, but over a year, you’ve gone miles.”

Crucially, these habits are designed to survive real life. “Life ebbs and flows,” Mills says. “Days unfold as we don’t expect them to.” In short, if a habit can’t flex, it won’t last.

open image in gallery

‘Quick Wins’ distils Mills’ philosophy into one-pan, low-effort cooking designed for tired evenings, not idealised wellness routines (Yellow Kite)

Nowhere is that realism more evident than in how Mills talks about evening meals – the moment many good intentions unravel. “It wasn’t that I didn’t have 15 or 20 minutes to cook,” she says of her own burnout period. “It was that I didn’t have the headspace.”

Her solution wasn’t discipline; it was structure. Loose meal plans, a weekend shop and knowing, on Tuesday night, post-school run, exactly what was for supper. “You get home and you think, ‘Right, I’ve got the ingredients, this will be ready in half an hour. Done.’”

This is where her latest book, Quick Wins, lives: food that feels comforting, requires minimal washing up and removes friction at the point of decision. Take her “fancy beans on toast”, a regular fallback. Garlic, chilli flakes and cherry tomatoes cooked down, butter beans stirred through, finished with lemon, yoghurt and basil, spooned onto toast. “It’s comfort food,” she says. “It takes 10 minutes. It’s not crazy ingredients. And you feel like you’re winning.”

Another go-to is a one-tray bake: peppers, red onion, tofu and spices roasted until crisp, garlic softened in its skin and squeezed into yoghurt, served with rice and avocado. “Five minutes of prep, one tray, one bowl,” she says. “That’s the middle of the Venn diagram for me – it has to be delicious, easy and genuinely nourishing.”

Mills is clear that toast or takeaway aren’t moral failures. “There’s nothing wrong with toast,” she says. “It’s just that adding things to the toast is more beneficial.” The goal isn’t perfection. It’s reducing decision fatigue so healthier choices become default, not heroic.

Mills has also watched – with some frustration – the way plant-based eating has been recast in recent years. What began as a movement towards whole foods became, briefly, a race towards technological substitutes: bleeding burgers, ultra-processed meat alternatives, the promise of eating “normally” without meat.

“We never believed that was the future,” she says of Deliciously Ella’s refusal to enter that market. “We passionately believe in basing your diet on whole food ingredients.” Her reasoning was simple: most people don’t want to be vegan; they want to eat more plants. “Unless you want to completely cut out meat, most people don’t necessarily want to swap a normal burger for a fake burger.”

I don’t think you can have a multri-trillion dollar industry that’s grown at that speed when we’re collectively getting more ill and say the wellness industry is a wild success. It’s making a lot of money. I’m not really sure it’s making enough people more well

Ella Mills

As enthusiasm cooled, so did consumer trust. “People started to realise these foods aren’t very good for us,” Mills says. “If I’m not going to eat a classic burger, I’d rather eat a bean burger that tastes completely different and that I can appreciate for being delicious.”

That nuance is often lost in today’s UPF discourse, which Mills believes risks becoming another source of anxiety. Label-scanning apps and absolutist rules, she argues, can slide into obsession. “The way you eat has to be joyful,” she says. “If you constantly feel like you’re compromising or depriving yourself, that’s not the way to live.”

Food, for Mills, is only one pillar. Stress management, sleep and movement matter just as much – but again, she favours the unglamorous. “Walking is so powerful for your health,” she says. So is community, connection and rest – the things least likely to trend on TikTok.

Her own routines reflect that pragmatism. Breakfast is non-negotiable, even if it’s overnight oats. Ten minutes of quiet in the morning – sometimes breathwork, sometimes just coffee in silence – helps buffer the day. She avoids social media before leaving the house. “I try not to look at my phone until I’ve sorted the kids out,” she says. “It really helps.”

When scrolling became unavoidable during her longer commute, she didn’t quit her phone – she changed how she used it. “I swapped Instagram for Netflix,” she says, laughing. “It doesn’t sound inherently positive, but it’s been great.” Watching a series, she explains, feels restorative in a way doomscrolling never did. “I’m not comparing myself. I’m not going into a fear hole. It’s escapism.”

That compassion extends inward. Mills is wary of the cultural reflex to push harder, optimise further, rest less. “There’s always this sense of, ‘Don’t rest. Be more productive,’” she says. “But if you get yourself on that treadmill, it’s really hard to be present.”

If all of this sounds modest, that’s the point. Mills’ only true non-negotiable isn’t a food rule or fitness target – it’s a mindset. “It’s telling myself exactly that: it’s enough. Good effort.”

That idea – of being “well enough” rather than perfect – underpins everything she now advocates. “You can always do more,” she says. “But if you’re constantly telling yourself you’re not doing enough, it’s not really worth it.”

Her advice for anyone staring down a new year of resolutions is disarmingly simple: don’t try to change everything. Change something small, and keep coming back to it. “If there’s something you want to do this year,” she says, “ask yourself if you can imagine doing it – not perfectly – but most weeks, for the next 10 years.”

If the answer is no, she’s blunt: “I wouldn’t bother.”

Because the real wellness “hack”, she believes, isn’t optimisation at all. It’s consistency, kindness and the quiet confidence of knowing you’ve done enough.