A new CAR T therapy targets the immune cells that protect tumors, reshaping the tumor microenvironment and enabling host immune clearance.

Cancer immunotherapy has transformed oncology by harnessing the immune system to recognize and destroy tumors. Approaches such as immune checkpoint inhibitors and engineered immune cells have delivered durable responses in some patients — and nowhere more dramatically than CAR-T cell therapies in blood cancers. Several CAR-T treatments are now FDA-approved and have produced long-term remissions in leukemia and lymphoma.

But that success has been far harder to replicate in solid tumors.

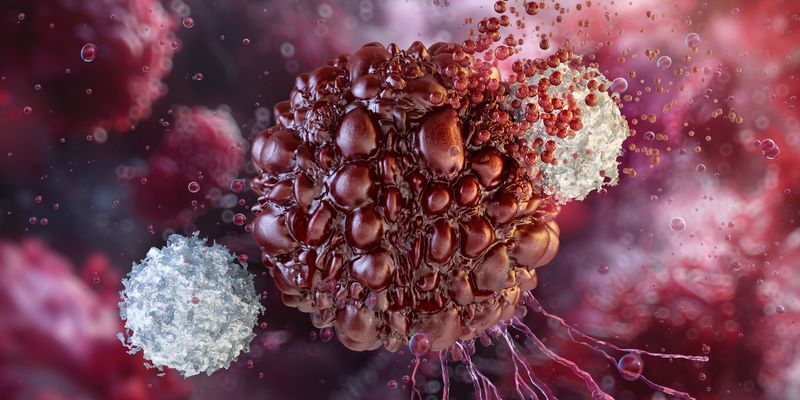

Unlike blood cancers, solid tumors create a hostile microenvironment that actively shuts down immune attack. Engineered T cells often struggle to infiltrate tumors, persist long enough to act, or remain functional once inside. As a result, researchers are increasingly shifting their focus away from cancer cells — and toward the immune ecosystem that surrounds and protects them.

In a new study published in Cancer Cell, researchers have described an experimental immunotherapy that targets tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) rather than cancer cells themselves, dismantling the immune shield that allows tumors to evade attack.

Tumors are more than cancer cells

“What we call a tumor is really cancer cells surrounded by cells that feed and protect them,” said Jaime Mateus-Tique, one of the study’s lead authors, in the news release. “It’s a walled fortress.”

TAMs are among the most abundant immune cells in solid tumors, making up as much as 50 percent of the immune cell population within the tumor microenvironment (TME). While macrophages normally serve as first responders to infection and tissue damage, tumors co-opt them, reprogramming these cells to suppress immune activity and support tumor growth and metastasis.

Continue reading below…

“If you just look at a histological section of an ovarian or lung tumor, you can see by eye that they are full of macrophages,” Brian Brown, Director of the Icahn Genomics Institute and senior author of the study, told DDN. “Our hypothesis was that if we eliminate the cells protecting the cancer cells, it would enable the endogenous killer T cells to then eliminate the cancer cells.”

There’s also another reason for targeting macrophages instead of cancer cells. “Cancer cells do not express many molecules that are different from the cells they derive from,” Brown said. “So, making a CAR T cell that targets a molecule expressed by cancer cells risks killing healthy cells that also express the same molecule.”

By contrast, years of tumor profiling has revealed that TAMs have upregulated specific markers — including FOLR2 (folate receptor 2) and TREM2 (triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2)— that are far less common on normal macrophages.

“We thought, let’s generate a CAR T cell to target these molecules, which are predominantly expressed by macrophages in tumors,” Brown says. “This can get our CAR T cells into a tumor, like a Trojan horse.”

A Trojan horse strategy

This strategy isn’t completely novel. Previous attempts using macrophage-targeting CAR T cells have shown promise in preclinical models. However, their effects have been short-lived, with tumors eventually rebounding. Based on earlier findings that interferon gamma (IFNγ) release is a key driver of anti-macrophage CAR T activity, the Mount Sinai team set out to enhance — or “armor” — these cells to make their effects more durable.

To do this, the researchers engineered CAR T cells that target TAMs expressing either FOLR2 or TREM2, and programmed them to secrete IL-12 (interleukin-12), a potent immune-activating cytokine. IL-12 activates T cells and drives the production of IFNγ — a cytokine that not only boosts T cell killing, but also reprograms macrophages toward an anti-cancer, immune-stimulating state.

“The unique thing about our approach is that we kill macrophages and ensure that the replacement macrophages don’t just become immunosuppressive again,” Brown said. “They become immunostimulatory macrophages. This creates a self-sustained reprogramming of the tumor microenvironment.”

Reshaping the TME

To understand how the therapy was changing tumors from the inside, the researchers turned to spatial transcriptomics, along with flow cytometry and multiplex imaging.

“The changes were not subtle,” Brown said. In treated tumors, cancer cells were almost entirely eliminated. But the most striking differences were in the immune landscape.

Spatial genomics revealed that after 10 days of treatment, tumors showed a completely different immune architecture. “Instead of macrophages expressing immunosuppressive molecules, they were expressing very immunostimulatory and anti-cancer molecules like MHC class I, CD40, TNF, and CYBB,” Brown said. At the same time, cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, the immune system’s primary cancer killers, more than tripled in number.

These immune changes translated into striking outcomes in preclinical models. Mice with metastatic lung and ovarian cancers survived for months longer after treatment, and many were completely cured.

A broad approach

One of the most compelling aspects of the strategy is its potential to work across many different cancer types. Since the therapy is targeting the immune cells that surround and protect tumors — rather than cancer cells themselves — it could be effective even in cancers that lack clear, targetable tumor antigens.

Continue reading below…

That distinction matters because the CAR T cells are not designed to kill cancer cells directly. Instead, they dismantle the tumor’s protective barrier and unleash the host immune system to clear the disease. Brown explained, “In data that we didn’t include in the paper we found that we could rechallenge the surviving mice with cancer cells, and they immediately eliminated the cancer cells. This is a hallmark of immune memory and must come from the host immune system since our CAR T cells were no longer present in the animals.”

The team is now working to refine the approach, particularly by controlling where and how IL-12 is released within tumors, to maximize effectiveness while maintaining safety. Beyond lung and ovarian cancer, the researchers believe the strategy could serve as a foundation for future CAR T therapies that reshape tumors by targeting their support cells rather than cancer cells alone.