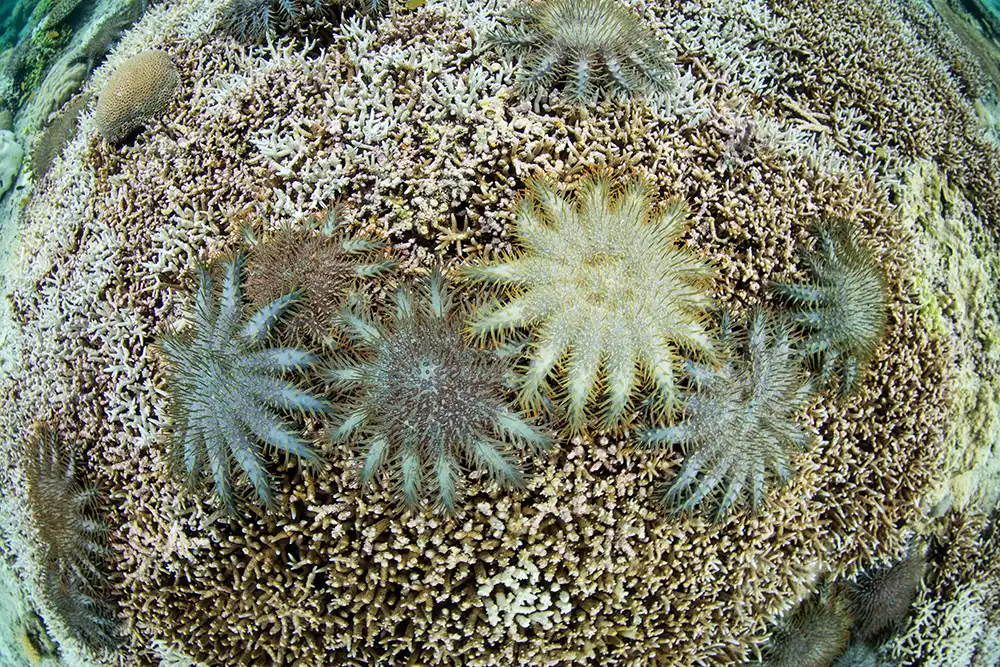

Crown of thorns starfish are voracious predators (Photo: Shutterstock)

Crown of thorns starfish are voracious predators (Photo: Shutterstock)

Scientists are responding to an emerging outbreak of crown-of-thorns starfish (COTs) on the Great Barrier Reef, warning it could develop into one of the most serious outbreaks seen in decades if not contained early.

Advertisement

The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (GBRMPA) said increasing numbers of crown-of-thorns starfish have been detected on a 240-kilometre (150-mile) long stretch of reef between Cairns and Lizard Island.

Crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster cf solaris) are corallivores (coral-eating carnivores) native to the Great Barrier Reef and other parts of the Indo-Pacific region.

They are important parts of the reef ecosystem at a natural density lower than one starfish per hectare, but problems arise when populations increase rapidly and the rate of coral consumption outpaces the reef’s ability to recover.

‘Crown-of-thorns starfish are a natural part of the reef ecosystem, but when their numbers explode, they can cause serious damage to coral,’ said Roger Beeden, GBRMPA’s chief scientist.

A large COTs outbreak can be devastating for the surrounding reef (Photo: Shutterstock)

A large COTs outbreak can be devastating for the surrounding reef (Photo: Shutterstock)

Scientists generally define outbreak conditions as densities of more than 10 to 15 starfish per hectare. During severe outbreaks, starfish numbers can rise far beyond that threshold, resulting in widespread coral loss over relatively short periods.

There have been four documented crown-of-thorns starfish outbreaks on the Great Barrier Reef since the 1960s. The most recent began in 2010 and continues to require management, making the new outbreak even more of a potential concern.

GBRMPA said current observations are consistent with the early stages of a new outbreak, prompting intensified monitoring and control efforts.

‘We’re beginning to see a build-up in adult crown-of-thorns starfish and we need to get on top of it as fast as we possibly can,’ Beeden said.

‘If left unmanaged, outbreaks can strip large areas of living coral and undermine recovery across otherwise healthy reefs.’

GBRMPA said response teams are prioritising high-value reefs for surveillance and targeted control as part of its Crown-of-thorns Starfish Control Program, which involves trained divers manually removing or injecting starfish to reduce their impact.

Long-term monitoring by the Australian Institute of Marine Science has identified crown-of-thorns starfish as one of the major drivers of coral decline on the Great Barrier Reef over recent decades.

Data from AIMS is used by reef managers to detect population increases early and guide intervention.

‘When we get very large numbers, they can have a very large impact upon coral cover on the Great Barrier Reef,’ said Beeden. ‘One single starfish can produce hundreds of millions of eggs, which can then spread through the marine park with the current flow.’

COTs are difficult to eliminate due to both their fecundity and remarkable capability for regeneration. Their spines are also venomous and, while generally not fatal to humans, are intensely painful.

Control is usually managed by injecting the starfish with vinegar or cow bile, which kills them rapidly without harming the surrounding environment. Where possible, they are often physically removed from the reef.

Beautiful but deadly, a COTS leaves a trail of devastation in its wake (Photo: Shutterstock)

Beautiful but deadly, a COTS leaves a trail of devastation in its wake (Photo: Shutterstock)

The stretch of the Great Barrier Reef where the outbreak is taking place is one of the most important parts of the reef for tourism, especially scuba diving, where many thousands of dives are made each year.

In response, the Reef Authority works with the tourism sector through the Tourism Reef Protection Initiative (TRPI), a long-running partnership that funds operators to assist with reef protection activities.

Under the programme, trained tour operators, including dive professionals, help monitor COTs outbreaks and assist with culling when possible to do so.

‘Protecting the Reef is not just an environmental priority – it is fundamental to the future of Reef communities, tourism jobs, and Australia’s most iconic natural asset,’ said Gareth Phillips, chief executive of the Association of Marine Park Tourism Operators (AMPTO).

‘Long before large-scale programs were established, tourism operators were on the water reporting outbreaks, supporting early intervention efforts, and working alongside scientists and the Reef Authority to protect the health of the Great Barrier Reef.

‘The current COTS control program is a strong example of what can be achieved when industry, science and government work together.’

Related articles

Crowley (known to his mum as Mark), packed in his IT job in 2005 and spent the next nine years working as a full-time scuba diving professional. He started writing for DIVE in 2010 and hasn’t stopped since.

![]() Latest posts by Mark ‘Crowley’ Russell (see all)

Latest posts by Mark ‘Crowley’ Russell (see all)