New Contemporaries is a useful exhibition. Every year, it selects a group of “early-career UK-based artists” hot out of art school and presents them to us in a touring show. In the 77 years it has been going — the first effort was in 1949! — it has survived numerous rewrites and its chief ambition remains to give young artists a chance.

Its record in this is impressive. From David Hockney to Damien Hirst, from Paula Rego to Chantal Joffe, scores of notable talents have been unearthed and displayed at New Contemporaries.

Unfortunately, being useful is not the same thing as being rousing. I am trying to remember the last time I came out of the annual round-up feeling powerfully moved, excited, pleasured, uplifted. And I can’t. Usually, as with the 2026 version, you feel mildly tickled at best.

• Read more reviews by Waldemar Januszczak

Divided between the two spaces of the South London Gallery in Peckham, the latest version feels decidedly timid. Meandering from location to location, the show has difficulty building up a head of steam. And none of its artists appears to have noticed any of the elephants in the room. Ukraine, Gaza, Trump, AI, climate change, immigration are all studiously avoided. Not even the Beckhams get a mention.

Varvara Uhlik is Ukrainian. Given what is happening in her homeland, you would expect her work to be filled with passion. But no. What she gives us instead is a carefully constructed metal slide descending into a neat pool of black water. There’s unease here; slides are meant to be fun. But as an artwork it feels overly conceptual and tricky.

It’s a recurring mood. Alia Gargum is from Libya. Her contribution is a tower of flapping green fabric entitled This Was a Mosque. The specific tonality of the green, the green of flags and Arabian domes, feels as if it started out with spiky ambitions to bring up Islamic issues. But somewhere along the line, it decided to be elegant instead.

Alia Gargum’s This Was a Mosque

COLIN DAVISON

The 26 contributors have been split into four thematic groups of the kind modern curators love: States of Being, Connection, Architecture, Environments. The Architecture section, in which Gargum and Uhlik find themselves, is more interested in absences than in presences, a reminder, I presume, that one of the selectors this year is Louise Giovanelli, an artist who has spent her entire career obsessing about curtains rather than the shows taking place in front of them.

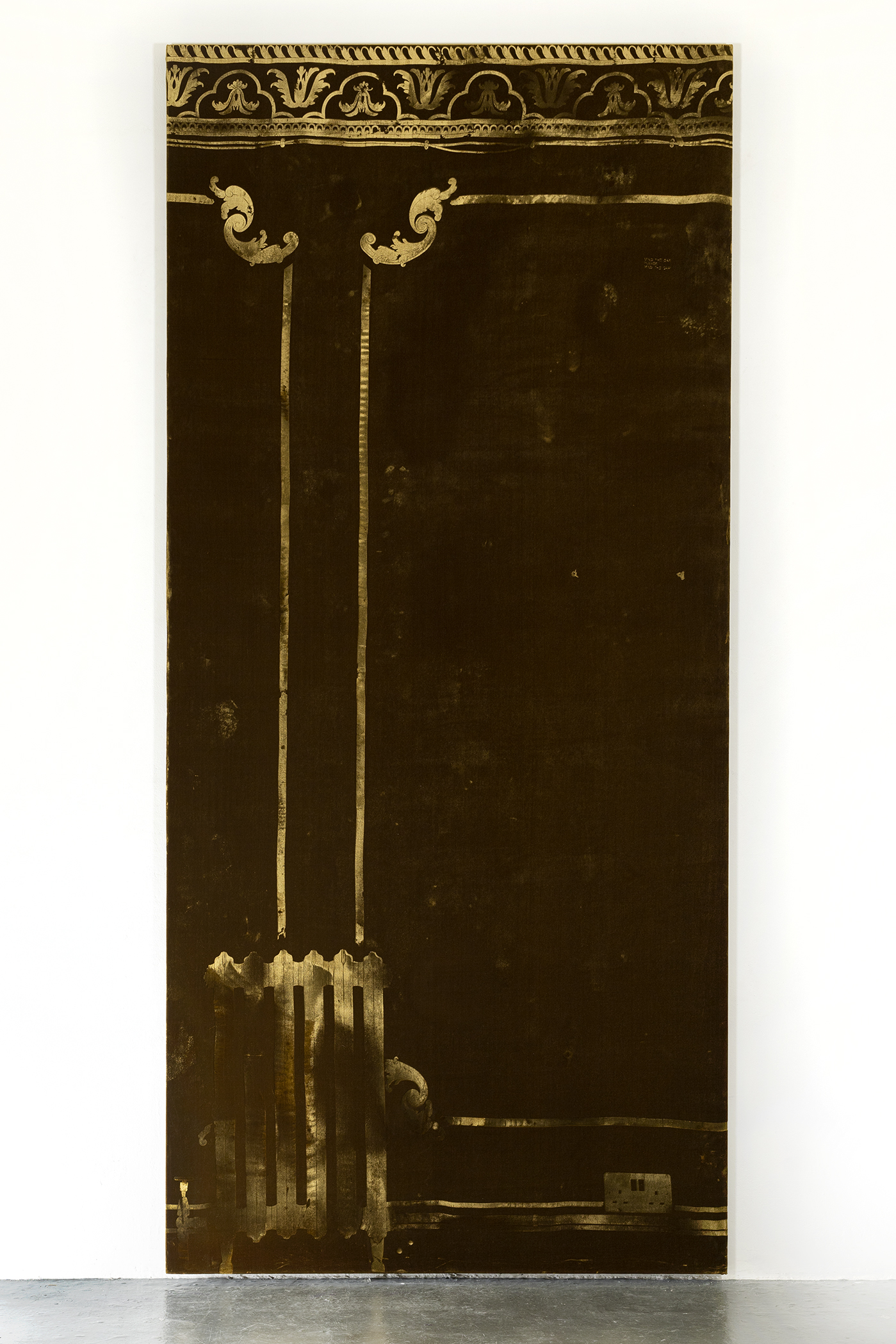

In a similar spirit, the Colombian artist Manuel Alejandro Hernandez Rivera, whose name demands the show’s biggest labels, presents a faded velvet wall on which we see the shadows of the radiator and the electric socket that were once attached to it. It’s a work about shifting fortunes and the passing of time. And the choice of faded velvet for the backcloth is poetically effective.

Manuel Alejandro Hernandez Rivera’s White wall variation one

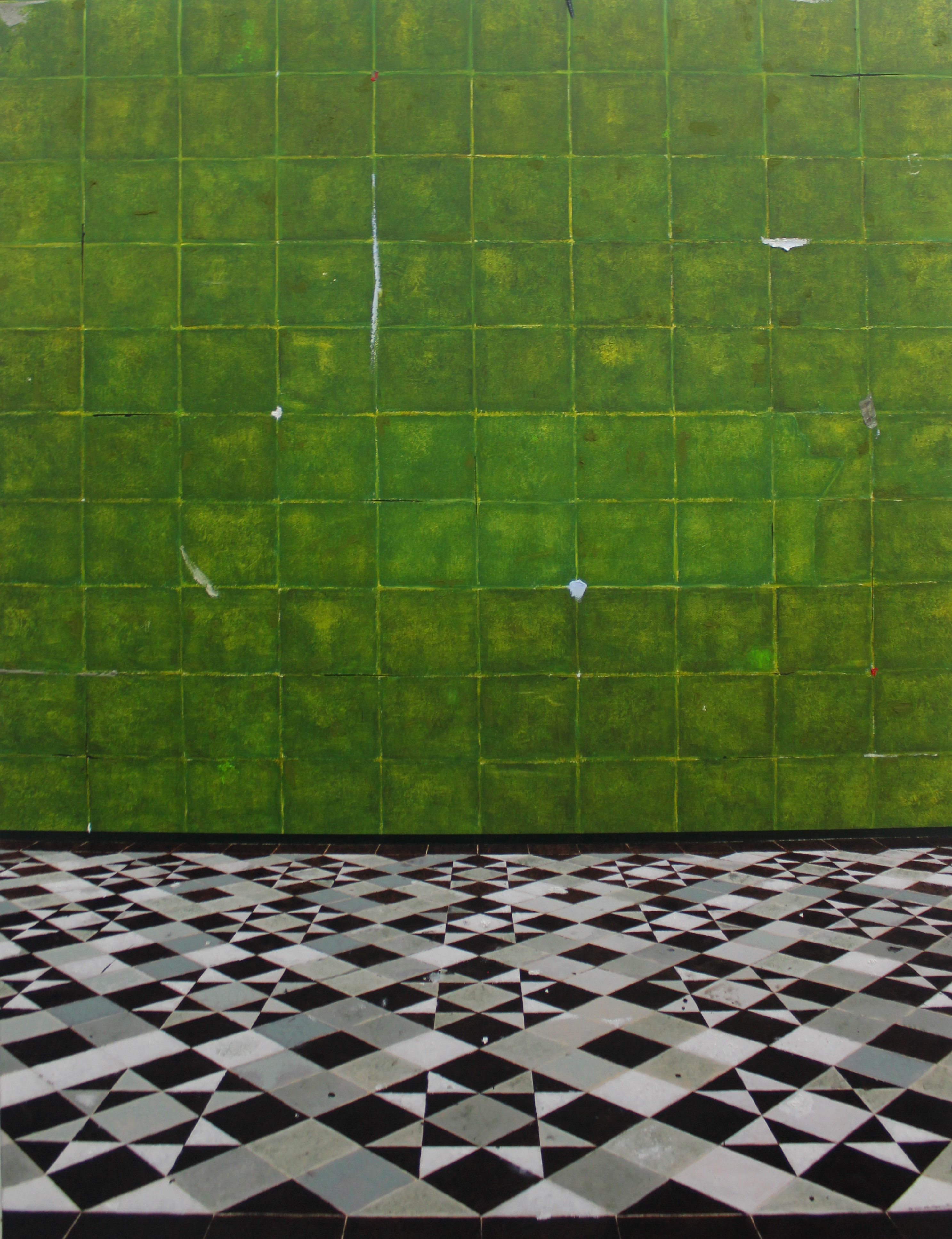

A little further down the wall, but still working the rich Giovanelli seam, Ally Fallon shows us the junction between a tiled floor and a tiled wall. The floor is geometrically decorated. The wall is plain green. Nothing else happens in the picture. But just as vacuums suck in oxygen, so architectural emptiness draws in our imaginings.

Ally Fallon’s In My Beginning Is My End

Elsewhere at the theme fest, States of Being turns out to be a fancy name for “identity issues”. With so many of the exhibitors coming from abroad, these are predictably popular. River Yuhao Cao is from China. His offering is a delicate film with fairytale moods about a nocturnal journey across a river that ends on the striking image of a Chinese “mourning truck”, a portable stage that travels from funeral to funeral on which an elegant female dancer enacts a last lament to sad and plucky music. It’s nicely shot and sporadically enchanting. But because it cannot possibly mean to us what it means to the artist, it ends up feeling like cultural tourism.

That said, States of Being turns out to be the show’s best section. Christopher Steenson, who is from Northern Ireland, has created an installation centred on the corncrake, a bird of the fields that was once plentiful in Ireland, but is now rare. Corncrakes, we learn, have a special place in the Irish sense of self. Even Gerry Adams, in a page of his autobiography included in the installation, sees something of himself in the disappearing bird.

So there are some decent moments here and plenty of variety with paintings, installations, photographs, sound works, sculptures and films. But instead of building a sense of exploration and adventure, the hopping about from medium to medium, style to style, feels tutored, as if everyone has been instructed to select from a contemporary book of patterns.

• Read more art reviews, guides and interviews

Indeed, the show as a whole appears over-curated, as if the art school system of today seeks to tame its students rather than release them. The days when art schools churned out John Lennons and David Bowies, Robbie Coltranes and Freddie Mercurys, are long gone. What used to be a launching pad for unruly talents that could not fit in elsewhere are now educational businesses charging impossibly high fees.

To go to art school today, especially if you’ve arrived from abroad, you need a rich mum and dad. The once fabulous Goldsmith’s School of Art in London charges foreign students £30,500 a year for a BA in fine art. That’s without accommodation and living!

Thus the passion, heat, wildness and sheer noisiness that artists used to exhibit at the start of their careers has been priced out of them. Like one of Rivera’s velvet walls, the old urgency of the British art school appears tragically to have faded.

New Contemporaries 2026 is at the South London Gallery, London, until April 12