Certain hidden fat patterns inside the body have emerged as markers of faster brain aging and greater loss of brain tissue.

The finding reframes brain risk as something that can build quietly, even in people who do not appear outwardly obese.

Inside detailed body and brain scans, the strongest warning signs appeared where fat settled deep in organs rather than under the skin.

By examining those scans, Dr. Kai Liu and colleagues at The Affiliated Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University (XMU) documented how pancreatic fat and so-called skinny fat tracked closely with shrinking brain regions and poorer cognitive scores.

These patterns stood apart from overall body weight, revealing that where fat accumulates can matter more than how much is visible from the outside.

That boundary sets the stage for a closer look at why some forms of hidden fat carry heavier neurologic consequences than others.

Six different fat patterns

Instead of treating all obesity the same, the researchers sorted people by where fat settled across the body.

They adjusted each fat measure for body mass index (BMI), a weight-for-height screening number used in clinics, then grouped similar patterns together.

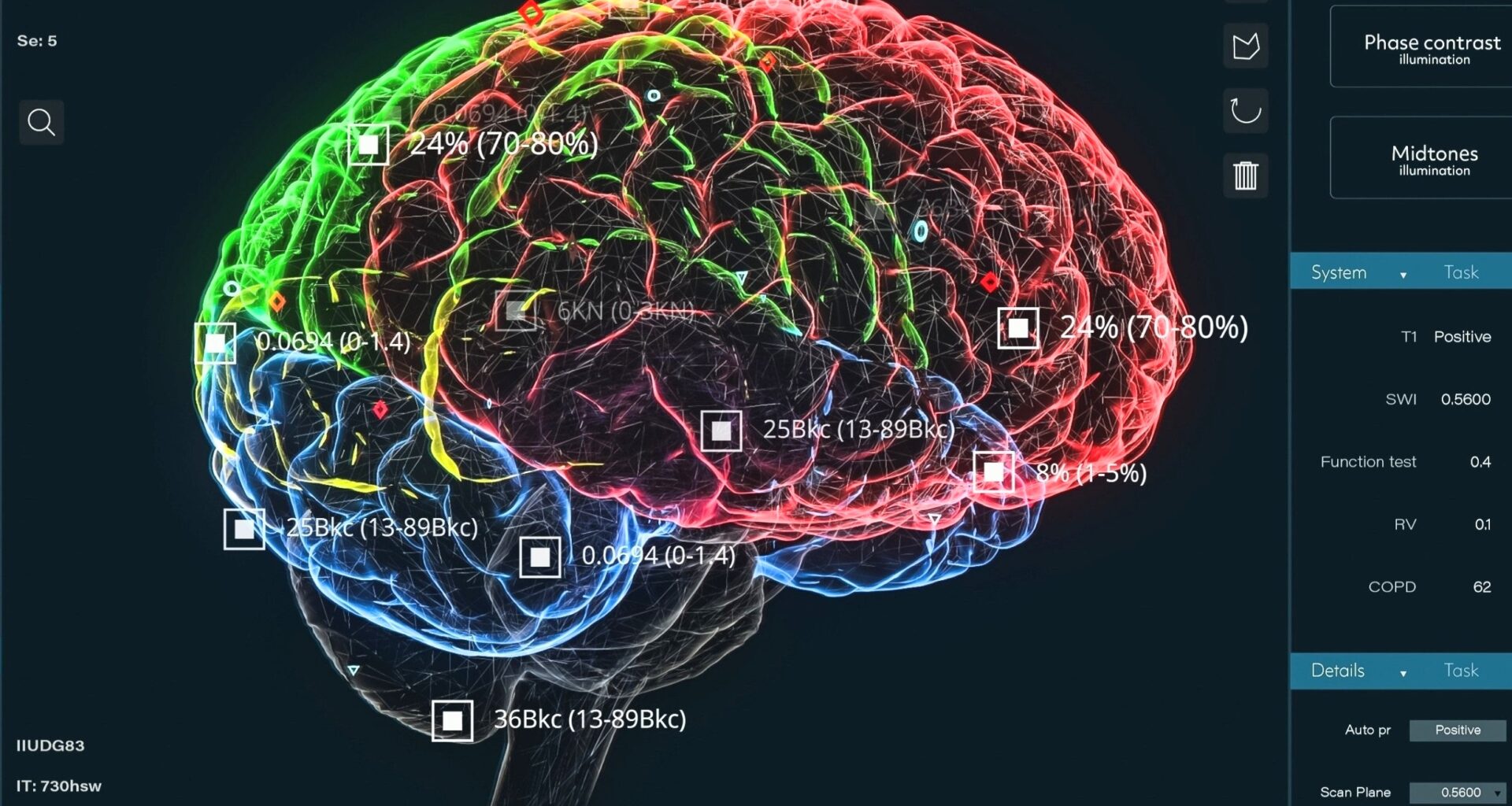

Magnetic resonance imaging, a scan that maps soft tissue clearly, served as their main tool, and MRI captured eight fat depots.

Out of six profiles created, two drew the strongest links to brain loss: pancreatic-predominant and skinny-fat.

Pancreas fat harms the brain

One high-risk group carried unusually heavy fat in the pancreas, even when MRI showed the liver did not look as fatty.

A short report described MRI estimates of about 30 percent fat in pancreatic tissue in detail.

The pancreas fat level ran two to three times higher than other categories and up to six times higher than lean people.

Normal weight, hidden danger

The skinny-fat profile looked less alarming on the outside, yet scans showed a high fat burden across much of the body.

Clinicians call this normal weight obesity, high body fat despite average weight, and it can hide behind routine measures.

Many in this group carried more fat in the belly and a higher weight-to-muscle ratio, body weight compared with muscle mass.

“Therefore, if one feature best summarizes this profile, I think, it would be an elevated weight-to-muscle ratio, especially in male individuals,” Liu said.

Organ fat causes inflammation

Fat becomes more than storage when it builds up in organs, where cells handle it differently than under the skin. This ectopic fat has been previously linked to insulin problems.

When tissues stop responding to insulin, glucose stays higher in blood, and that fuels inflammation that can damage small vessels.

That same stress can also reach the brain, since blood vessel injury and inflammation often travel together across the body.

Brain shrinks with fat

Past imaging work already tied abdominal fat to brain changes, and a 2023 review summarized those links.

The current study went further by matching fat profiles with gray matter, brain cells that process information, and it found broad loss.

The researchers also saw more white matter hyperintensities, bright spots linked to small vessel injury, in those higher-risk profiles.

Those markers lined up with older-looking brains in men, raising concern that damage can build before clear symptoms.

Memory and speed decline

Brain scans were not the only signals, since several thinking tests showed weaker performance in the higher-risk profiles.

On a quick matching task, some participants needed about 543 milliseconds to respond, compared with 517 milliseconds in the lean group.

Memory also declined, including prospective memory and visual recall, and men with the skinny-fat pattern showed sharper drops.

These were small differences for an individual, but they mattered at population scale because they tracked with brain structure changes.

Stroke and depression

Medical records added a sharper edge, because high-risk fat patterns lined up with higher odds of several neurologic disorders.

Men in the skinny-fat profile had about three times higher odds of a depressive episode and nearly twice the risk of stroke.

Women with pancreatic-predominant fat showed more than twice the odds of stroke and more than three times the risk of epilepsy.

Limitations of the study

Even with imaging, the study could not show that fat patterns directly caused cognitive decline.

The researchers measured fat and brain features at one point in time, so earlier illness or long-term habits could shape both.

Follow-up scans over years would help test whether changing fat stores changes brain trajectories, and whether sex differences persist.

The findings suggest that hidden fat in the pancreas or paired with low muscle may flag brains under stress.

If clinics start measuring organ fat and muscle more often, they could spot higher-risk patients earlier and study targeted prevention.

The study is published in the journal Radiology.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–