Small flaws hidden inside batteries are quietly limiting how fast they can charge and how safely they can operate. As rapid charging becomes the norm for phones, laptops, and electric vehicles, those tiny defects are turning into a big problem.

The challenge is especially sharp in solid-state lithium metal batteries, which replace flammable liquids with hard ceramic layers.

While that swap promises safer, more powerful cells, the solid layer can crack under pressure during charging or manufacturing. Once a crack forms, lithium can push its way inside and trigger sudden failure.

Now, engineers at Stanford University report a subtle way to toughen that vulnerable layer before damage spreads.

The team explored how small surface changes could help solid batteries survive the stresses of fast charging without slowing the flow of power.

The promise of solid batteries

Most lithium-ion cells use a liquid electrolyte, the ion-carrying fluid between the two electrodes, and that solvent can burn if damaged.

Solid versions swap that liquid for a ceramic or glasslike slab that lets ions move while blocking leaks.

A 2022 review noted that dangerous heat and gas can still appear when lithium grows uncontrollably inside solid batteries.

That risk keeps researchers focused on the hard middle layer, because it must endure both chemical reactions and mechanical pressure.

Silver boost from within

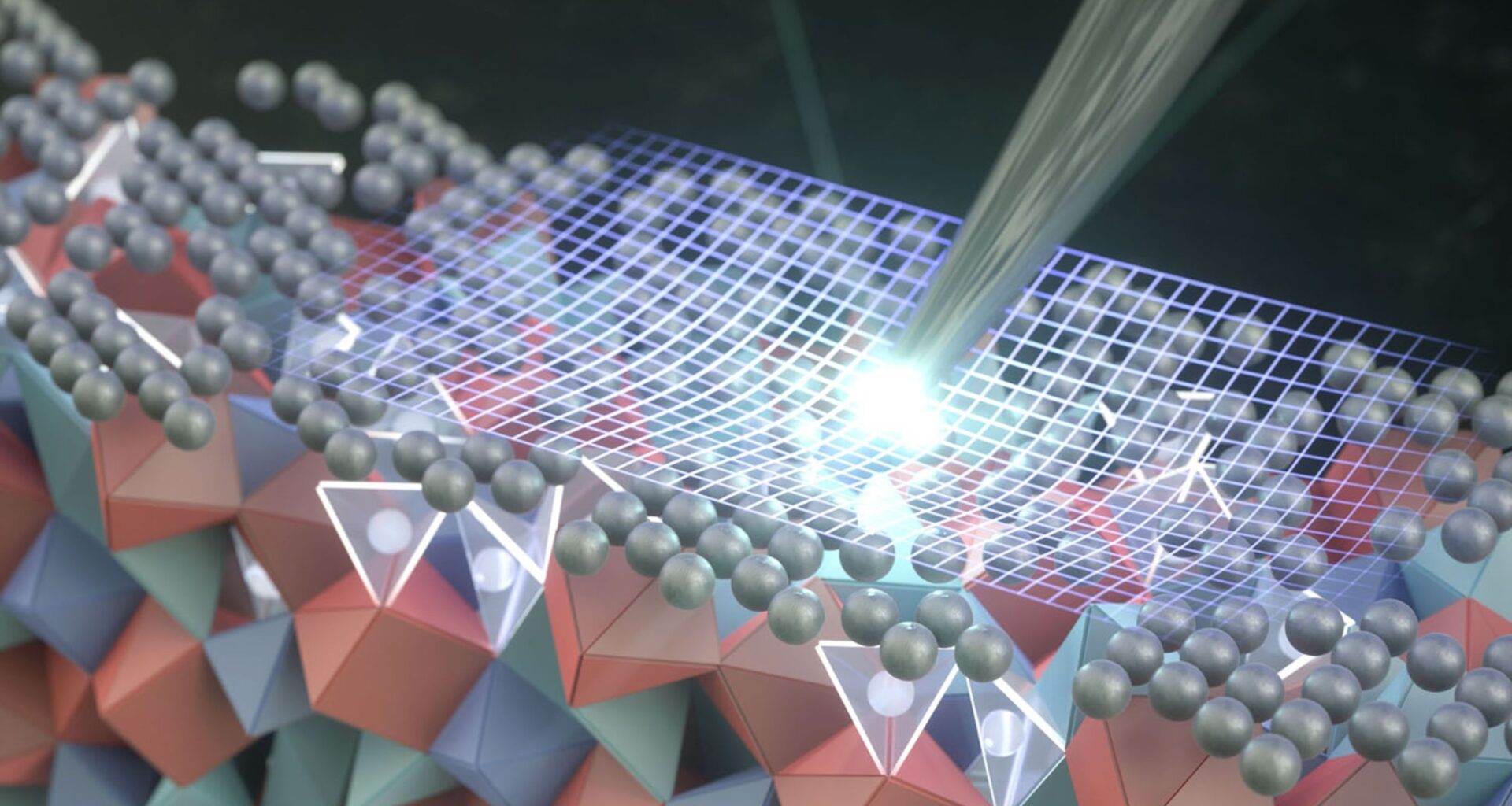

The work centered on a hard ceramic called LLZO, a material already used in experimental solid-state batteries to carry lithium without flammable liquids.

The researchers added an extremely thin layer of silver to the surface and gently heated it, allowing the metal to slip just beneath the outermost layer.

At that shallow depth, some silver atoms took the place of lithium rather than forming a separate coating. That subtle swap strengthened the surface from the inside out, without adding bulk or interfering with how lithium or electricity moves.

By crowding the surface slightly, the silver created steady internal compression that makes cracks harder to start and spread.

In battery-like conditions, that added toughness also limited lithium from forcing its way into tiny flaws during charging, lowering the risk that small defects could turn into short circuits.

Testing battery cracks under pressure

To measure strength directly, the team pressed a tiny probe into the material until cracks formed.

The silver-treated surface withstood nearly five times more force before breaking than the untreated version, showing that it was tougher even before any charging began.

That matters during manufacturing and handling, when solid battery layers are routinely cut, stacked, and compressed.

The added strength also changed how lithium behaved during fast charging. When lithium builds up quickly on the anode, it can form needle-like dendrites that drive stress into surface cracks and push them deeper.

On the silver-treated surface, cracks formed differently, encouraging lithium to spread across the surface instead of drilling inward.

This wider plating behavior could buy valuable time during high-current charging, though it still needs confirmation in full battery cells.

Searching for cheaper fixes

Silver is helpful but not cheap, so the researchers tested other metals that might deliver similar surface toughening.

Early lab trials suggested copper could also harden LLZO, because its ions can fit into surface sites after heating.

“We decided a protective surface may be more realistic, and just a little bit of silver seems to do a pretty good job,” said study co-author X. Wendy Gu, a professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering at Stanford University.

That flexibility matters as demand for lithium batteries keeps rising and supply chains face increasing pressure. The same surface strategy could even aid sodium cells later, which might ease pressure on lithium supply chains.

Taking coatings beyond the lab

So far, the silver treatment has only been tested on small electrolyte samples, not on complete battery cells with both electrodes attached.

Full cells introduce new failure points at their interfaces, where poor contact can slow ion flow and raise heat.

Even so, the coating did not noticeably change how electricity or lithium moved at the surface, pointing to added mechanical strength as the main source of improvement.

Across the study, this surface-focused fix turned a familiar weak spot into a tougher barrier against cracking and lithium intrusion.

If future tests confirm that durability holds across many charge cycles, the approach could pair with other strategies aimed at stabilizing solid-state batteries.

The challenge of mass production

Moving from the lab to the factory adds another layer of challenge. Solid electrolyte sheets are cut, stacked, and compressed thousands of times during assembly, making tiny imperfections almost unavoidable.

As one researcher noted, producing perfectly flawless layers at scale would be extremely difficult and costly.

Whether the silver-treated surface can survive those realities will decide if the technique reaches commercial batteries. Manufacturers will also have to manage costs and recycling impacts.

The study is published in the journal Nature Materials.

Image credit: Chaoyang Zhao

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–