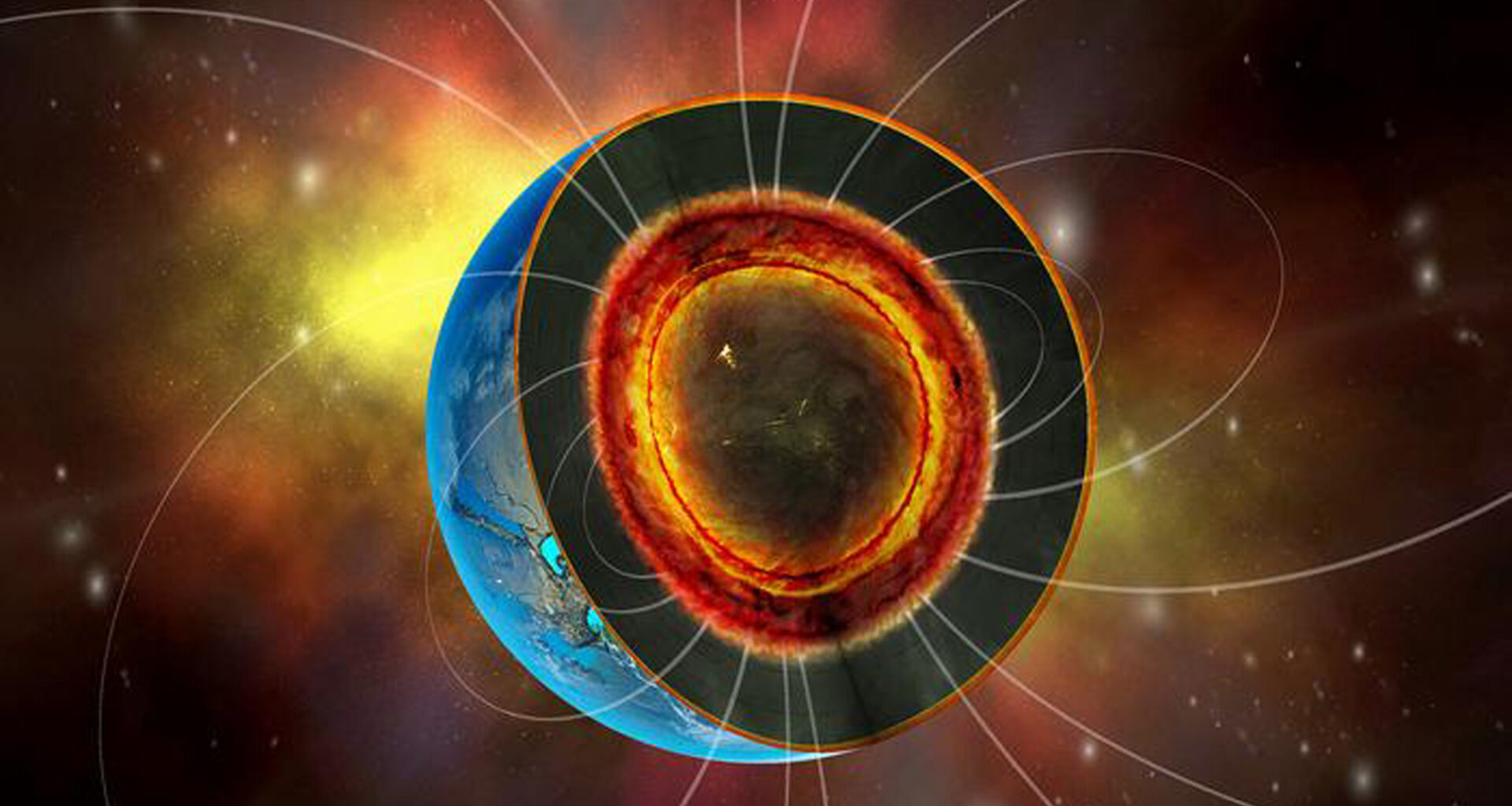

Deep layers of molten rock inside large rocky planets have been shown to generate magnetic fields strong enough to persist for billions of years.

Such long-lived shields can decide whether a planet holds onto its atmosphere or is slowly stripped bare by radiation.

Under the extreme pressures found deep inside super-Earths, molten mantle material has been observed to become electrically conductive in ways that can power planetary magnetism.

Miki Nakajima and colleagues at the University of Rochester document this behavior by showing that compressed mantle melt can sustain electric currents under interior planetary conditions.

Her research focuses on violent planet formation and the hidden layers that decide whether atmospheres survive long enough for chemistry.

New results tie that survival to magnetic fields generated within layers of deep molten rock.

Why magnetic shields matter

Life on land depends on a magnetosphere, a magnetic bubble that steers charged particles away from the surface.

On Earth, swirling liquid iron in the outer core generates currents, and those currents build the global magnetic field.

When stars release charged gas and high-energy particles, magnetic fields can steer much of that material away.

Many rocky planets appear to lose that protection, so magnetism has become a key habitability checkpoint for astronomers.

Bigger planets break old rules

Astronomers keep finding super-Earths – planets more massive than Earth yet lighter than Neptune – around other stars.

Their extra mass squeezes interiors hard, changing how iron and rock behave and sometimes leaving a core that stops stirring.

A planet can have a solid core too stiff to flow, or a fully liquid one without the right layering.

Either way, the classic iron-core engine for magnetism can fade, even while the surface still looks rocky.

A second magnetic engine

Early Earth likely carried a deep molten layer, and larger rocky planets may keep it long after surfaces harden.

Researchers call this layer a basal magma ocean, a melt zone resting at the mantle’s bottom.

If the melt conducts electricity, its slow circulation can drive a dynamo, the process that converts fluid motion into a magnetic field.

That idea changes the habitability math, because a magnetic field might survive even when an iron core cannot.

Rebuilding alien pressures here

At URochester’s Laboratory for Laser Energetics, pulses hit targets and launched shock waves – pressure fronts that squeeze materials fast.

“This work was exciting and challenging, given that my background is primarily computational and this was my first experimental work,” said Nakajima.

Those brief tests then informed computer models that estimated whether the same melt could remain active for billions of years.

Under crushing pressure, molten rock that normally blocks electric current began to carry it, behaving as a conductor rather than an insulator.

The pressure pushed atoms closer together, allowing electrons to move more freely and lose less energy.

At deep pressures, magnesium oxide and lightly iron-tinted versions showed similar conductivity. In both cases, the molten material could carry electric current.

That result undercut earlier expectations that iron would boost current flow by orders of magnitude in the deepest melt.

Scale makes shields last

Planet size mattered because thick mantles hold heat and keep the deep melt moving for much longer.

As a world grows, convection spans a larger distance, and faster flow strengthens the magnetic feedback that keeps fields stable.

Models suggested planets above three to six times Earth’s mass could sustain magma-driven fields almost ten times stronger for several billion years.

Even then, a strong field was not guaranteed as cooling rates and internal composition determine whether the melt keeps moving.

Finding fields from far

Magnetic fields do not show up directly in most telescope images, so researchers hunt for indirect signs.

One approach looks for radio emission produced by aurora-like activity when stellar particles collide with a magnetized planet.

Another path tracks how stellar outbursts disturb a planet’s upper atmosphere, since magnetic defenses can change the timing and pattern.

Even promising signals can have other causes, so a magnetic field claim usually needs several lines of evidence.

Why magnetism is not enough

Habitability still depended on many details, from a star’s flare behavior to whether a planet can keep water and air.

“A strong magnetic field is very important for life on a planet,” said Nakajima.

A deep-melt dynamo could help by lowering atmospheric erosion, because fewer charged particles reach the upper air with enough speed.

Yet a field alone could not guarantee habitable ground, since temperature, chemistry, and time also set the limits for biology.

By linking deep molten rock to long-lived magnetism, the work expanded the range of rocky planets considered promising for habitability studies.

If upcoming observations can spot these fields, researchers will better judge which super-Earths hold atmospheres steady for billions of years.

The study is published in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Photo credit: University of Rochester Laboratory for Laser Energetics illustration / Michael Franchot

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–