Chronic constipation is one of the most common disorders of gut-brain interaction, affecting around one in ten adults worldwide. It has a substantial impact on quality of life and is associated with economic burdens, including direct costs and lost productivity1.

Emerging evidence suggests that gut transit time is a key factor in shaping the gut microbiota composition and metabolic activity, which is likely to have implications for constipation and long-term gut health. While people often first try dietary changes to manage constipation symptoms, existing guidelines for constipation management generally include limited dietary advice, focusing mainly on increasing fiber intake and ensuring adequate fluid intake1.

The new British Dietetic Association (BDA)’s guidelines provide the first comprehensive, evidence-based recommendations for the use of supplements, foods and drinks, and whole diets for chronic constipation2,3.

The guidelines were developed through four systematic reviews and meta-analyses of 75 randomized controlled trials and appraised using the GRADE approach with a Delphi consensus process.

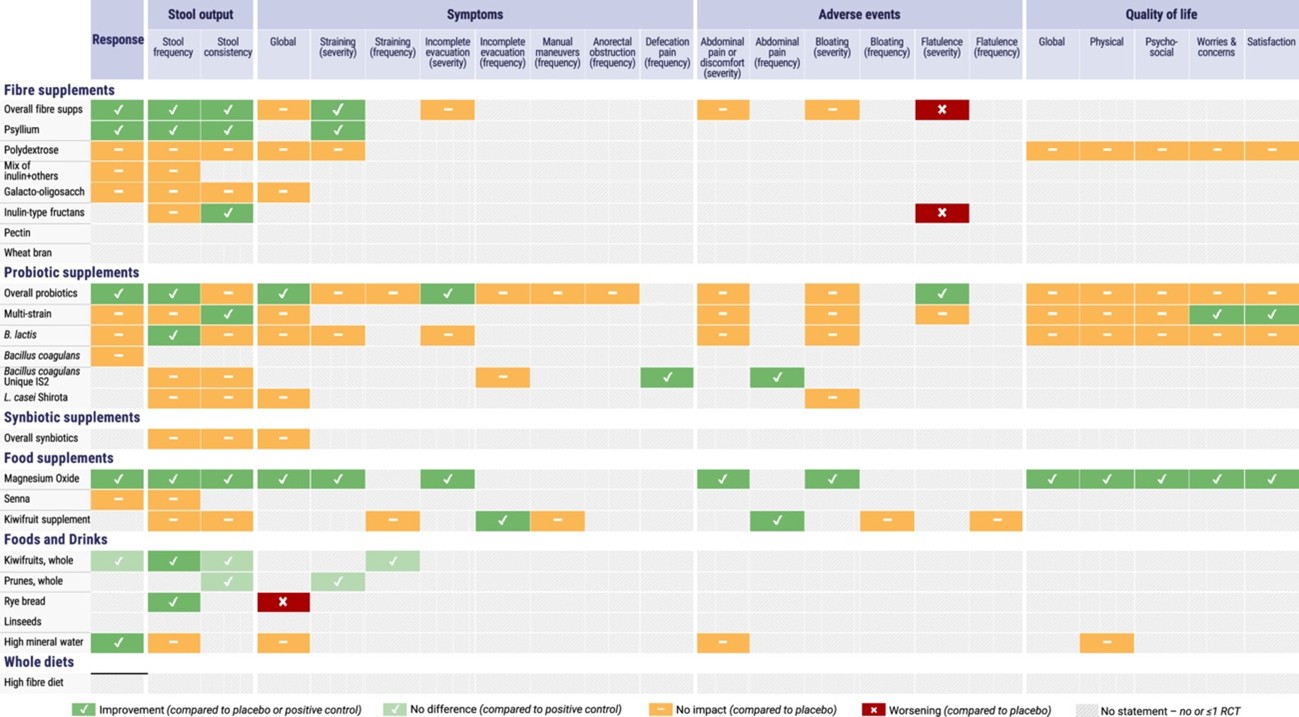

A total of 59 recommendations are included in the guidelines, with evidence supporting the use of kiwifruits, prunes, rye bread, and high-mineral-content water. Six randomized controlled trials (RCTs) showed that 2-3 kiwifruits per day might increase stool frequency and lower global gut symptoms. In particular, kiwifruits were associated with fewer side effects than prunes or psyllium supplements. Moreover, two RCTs showed that 6-8 slices of rye bread a day might increase stool frequency and shorten gut transit time, but might worsen gut symptoms compared with white bread. High-mineral-content water was another intervention that, compared with tap or low-mineral-content water, improved response to treatment in 4 RCTs.

Probably a synergy of multiple components in foods is responsible for their effects on specific outcomes of constipation. In particular, prunes and kiwifruits have been shown to modify the gut microbiota in human studies, with prunes increasing fecal weight and kiwifruits increasing small bowel and fecal water content4. To what extent water with high mineral content improves constipation through shaping the gut microbiome is unknown.

Beyond foods and drinks, several supplements can help relieve constipation. Psyllium supplements, kiwifruit supplements, magnesium oxide supplements, and certain probiotic strains might improve specific constipation outcomes. Multiple RCTs (n = 16) consistently showed that psyllium (ispaghula fiber) might improve stool output and straining, with optimal effects at doses higher than 10 g/day and longer treatment durations (³4 weeks). Based on 30 RCTs investigating probiotics, their effects were species-, strain-, and outcome-specific. Notably, Bifidobacterium lactis, Bacillus coagulans lilac-01, Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938, and Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 might improve stool frequency. Kiwifruit supplements might improve incomplete evacuation and abdominal pain. Magnesium oxide supplements (0.5-1.5 g/day) have been shown to consistently improve constipation outcomes, including response to treatment, stool frequency, stool consistency, and global constipation symptoms; note that the dose should be gradually increased to a monitored tolerance level.

Mechanisms by which probiotics could exert an effect on gut motility and constipation include affecting intestinal regulatory T cells, shaping the gut microbiota and fermentation byproducts, which in turn seem to affect gut motility via the enteric nervous system, rather than the brain-gut axis5.

However, there was insufficient evidence to support whole-diet approaches for constipation, including the traditional advice of adopting a high-fiber diet. In addition, there was a paucity of evidence for other interventions, including specific probiotics (e.g., Lactobacillus casei Shirota), prebiotics (inulin-type fructans softened stool consistency, but not resulted in a clinically meaningful effect), synbiotics, and senna supplements. Moreover, no eligible RCTs were found for oats and linseeds, so it is not possible to make any recommendation on their benefits for constipation.

A clinician-friendly tool has also been developed to support the implementation of these guidelines in everyday practice:

Source: Dimidi E, van der Schoot A, Barrett K, et al. British Dietetic Association guidelines for the dietary management of chronic constipation in adults. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2025; 38(5):e70133. doi: 10.1111/jhn.70133.

The BDA guidelines for chronic constipation highlight the importance of high-quality evidence in guiding dietary interventions for the management of disorders of gut-brain interaction. They also remind us that nutrition clinical trials face more challenges than trials of pharmacological interventions, especially given methodological issues, the complex composition of foodstuffs, monitoring of adherence, and the impact of background diet and diet-microbiome interactions on studied outcomes6.

While current evidence does not support some dietary interventions that target the gut microbiome in healthy adults with chronic idiopathic constipation, they could be worth trying in specific clinical contexts. For instance, in patients with Parkinson’s disease, a fermented milk with probiotics and prebiotics showed to improve constipation without major adverse events. With evidence now catching up the benefits of dietary interventions in constipation outcomes, healthcare professionals have effective options to offer to their adult patients with chronic constipation instead of the vague advice of eating more fiber, drinking more water, and do more physical activity.

References:

- The Lancet Gastroenterology Hepatology. Bridging the evidence gap in dietary approaches to gut disorders. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025; 10(12):1053. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(25)00326-7.

- Dimidi E, van der Schoot A, Barrett K, et al. British Dietetic Association guidelines for the dietary management of chronic constipation in adults. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2025; 38(5):e70133. doi: 10.1111/jhn.70133.

- Dimidi E, van der Schoot A, Barrett K, et al. British Dietetic Association guidelines for the dietary management of chronic constipation in adults. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2025; 37(12):e70173. doi: 10.1111/nmo.70173.

- Katsirma Z, Dimidi E, Rodriguez-Mateos A, et al. Fruits and their impact on the gut microbiota, gut motility and constipation. Food Funct. 2021; 12(19):8850-8866. doi: 10.1039/d1fo01125a.

- Dimidi E, Scott SM, Whelan K. Probiotics and constipation: mechanisms of action, evidence for effectiveness and utilisation by patients and healthcare professionals. Proc Nutr Soc. 2020; 79(1):147-157. doi: 10.1017/S0029665119000934.

- Staudacher HM, Yao CK, Chey WD, et al. Optimal design of clinical trials of dietary interventions in disorders of gut-brain interaction. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022; 117(6):973-984. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001732.

\\r\\n\\r\\n\\r\\n\\r\\n\\r\\n\\r\\n\”,\”body\”:\”\”,\”footer\”:\”\”},\”advanced\”:{\”header\”:\”\”,\”body\”:\”\”,\”footer\”:\”\”}}”,”gdpr_scor”:”true”,”wp_lang”:”_en”,”wp_consent_api”:”false”};

/* ]]> */