On set, a young director named Victor Velle was rehearsing the train-station scene with the actors playing George and Uncle Jack. Velle, who wore a neck brace (Fourth of July diving accident), was joined by Katya Alexander, who had worked at the Sphere before Saatchi hired her as Fable’s head of production. They would shoot the actors talking face to face, to create emotional depth, but then separate them for the A.I. work, which for some shots required the use of a motion-controlled robotic camera.

“It’s not just putting together this puzzle,” Velle said. “It’s re-creating the pieces so that the puzzle fits together.” Tiny dramaturgical details had been lost to time. In the train station, Uncle Jack holds an umbrella while accepting cash from George. “Is it going to be weird for him to fumble with an umbrella as he puts the money in his pocket?” Alexander asked. “How does he pick up the suitcase? We don’t have a shot of him picking it up.”

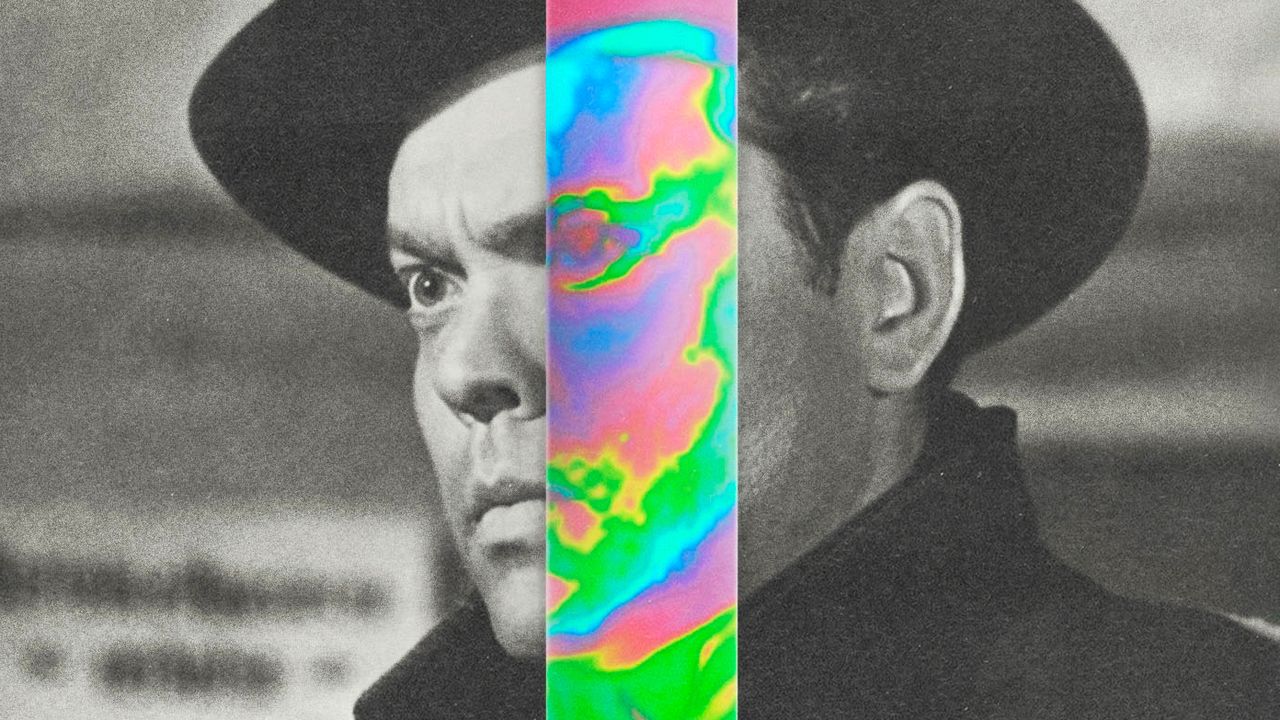

Velle added that Welles’s actors often handled props in an “aesthetically pleasing” way: “Orson is the king of cool, so how to do it with his flavor?”

They had put out a call for actors in Backstage, seeking not exact look-alikes but people with what Velle described as a “regal nineteen-forties vibe.” He said, “In that period, a lot of people would act as if they had tons of Botox—their foreheads don’t move.” The three actors they hired worked with a coach, Kimberly Donovan, to study their 1942 counterparts. “You’re reverse engineering someone else’s performance,” Donovan told me. Holt, for example, “attacks every word,” whereas Moorehead’s delivery can be “soft and kitten-like.”

Cody Pressley, an actor with a sonorous Wellesian voice, was playing both George and Eugene in separate scenes. Pressley said that he often gets cast in period pieces. (Previous roles include Gerald Ford’s photographer in “The First Lady” and a drunk teen in “Stranger Things.”) He’d been camping in Colorado when he got the call from Fable and rushed back to L.A. “It’s so very technical,” he told me. “You have to match the cadence of an actor from the forties. You have to match the words verbatim. And you basically have to keep your head still.”

They started shooting the scene. John Fantasia, who was playing Uncle Jack, stumbled over a wordy bit of dialogue. “Cut!” Velle yelled. He gave Pressley a note: “George’s voice is a tiny bit higher pitch than what you did.” They rolled again, as the robotic camera whirred. Later, Fantasia told me that he had limited knowledge of A.I. “As an actor, I thought, I don’t think I’ll ever want to do this, because it’s contributing to the downfall,” he said. “But then I thought, It’s already seeped into the Hollywood subculture.” Plus, he added, “it’s a paying gig.”

In the afternoon, Saatchi and Rose took me to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’s Margaret Herrick Library. The two made an odd couple. Saatchi was in minimalist black-and-white, in the style of a Silicon Valley guru. Rose, who had flown in from Missouri, wore a tucked-in plaid shirt with a tie and had a Nikon camera hanging from his shoulder, like a tourist at Niagara Falls. We sat in a reading room and opened a folder of weathered correspondence. First came a letter dated August 18, 1941, in which the R.K.O. employee Reginald Armour gushed to Welles, “If the picture turns out to be as good as the script, you already have another smash hit on your hands.”