Prime Time’s Conor Wilson travelled to Estonia and Finland to understand how the two countries are dealing with an increase in hybrid warfare activity, four years on from Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, which massively heightened tension across eastern and northern Europe.

In the wake of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Mart Luik set up ‘Slava Ukrainia’, a restaurant in the centre of Estonia’s capital city, Tallinn, to help those displaced by the war.

In January last year, he woke to a phone call to say that the restaurant was on fire.

By the time he arrived, the fire was out, but clear CCTV footage of how it started was soon obtained.

“Basically, it was all there”, Mr Luik told Prime Time. “We saw how the guy prepared himself, smashed the window to throw the liquid into the cafeteria, set the fire and caught fire himself as well. You could see the burning man running towards the harbour area.”

Two men were on the scene, one lighting the fire and the other filming the action.

Both suspects were soon identified. They turned out to be Moldovan nationals. After a two-week investigation involving law enforcement agencies from several European countries, they were arrested in Italy.

Last July, they were convicted and jailed.

One was found guilty of arson committed in the interests and carried out on behalf of the intelligence services of another country.

The prosecution detailed how Ivan Chihail had been contacted by the GRU – Russian military intelligence – months beforehand, and previously been tasked with similar attacks, receiving payment in cryptocurrency.

To carry out the attack on the Slava Ukrainia restaurant, he recruited the other man – a relation. The accomplice had no idea that he was working on behalf of the GRU. He was sentenced to two-and-a-half years.

The investigation into the arson involved Polish, Lithuanian, Latvian, Estonian and Italian agencies. That such a scale of co-operation was put in place for what was a relatively minor crime speaks to the lengths Estonian police and intelligence services go to when they suspect an incident is more than routine.

They consistently do something services in few other European countries manage to do: attribute blame for hybrid attacks. It is not an easy process but something that Estonian services try to do whenever possible.

“When there is a reason to say it out loud, then we are saying that out loud,” Hanno Pevkur, Estonia’s Minister of Defence, told Prime Time.

“We have no reason to hide it. When you have proof and when you have the evidence, then I believe it is right to say to your citizens that this is the hybrid warfare or this is an operation which was operated and orchestrated by the Russian services.

“Russia is conducting that type of attacks and we have to be vigilant.”

Hanno Pevkur, Estonia’s Minister of Defence

Other cases have involved cyber attackers, or simple vandalism: for instance, the windows of cars belonging to anti-Kremlin politicians and prominent journalists were smashed.

The efforts of Estonian intelligence and law enforcement agencies are intended to undermine one of the defining characteristics of hybrid warfare activity: ambiguity.

Hybrid warfare is a type of military- or intelligence-linked activity that tries to leverage plausible deniability to disrupt a target country’s economy, society, or information environment, without provoking a direct or even similar response.

It is also the phrase on the lips of many senior military officials and politicians across Europe, in particular since the war in Ukraine ramped up.

Yet while many countries have claimed to have been subjected to an uptick in hybrid attacks in recent years, few have managed to obtain the evidence to back it up, leaving them open to accusations of pearl-clutching and Russophobia.

The recent dramatic spike of drone sightings across Europe is a good illustration. Flights were cancelled and airspace closed in many northern European countries between September and December last year, following reported sightings of drones in the vicinity of airports and air bases.

In the Netherlands, the Dutch military even opened fire on a suspected drone above one of its airbases. After reported drone activity closed Danish airports, the Danish Prime Minister called it a “serious attack” without ever attributing blame.

None ever released evidence to confirm that the drone activity actually occurred.

As a result, to some, the series of incidents – including reported drone activity off Dublin during the visit of Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky – is evidence of mass hysteria, social contagion or collective delusion, rather than hybrid warfare.

Russian President Vladimir Putin dismissed the idea of Russian involvement when asked about the reported sightings in October. “I won’t send any more (drones),” he said, laughing.

Russian President Vladimir Putin dismissed the idea of Russian involvement in airport drone activity

The pursuit of convictions in Estonia is intended to undermine the potential for such dismissiveness. However, experts say a lack of convictions elsewhere should not be taken as an absence of evidence that hybrid warfare is ongoing in parts of Europe.

In Romania, investigators found in May that hundreds of cameras at border crossings had been hacked as part of a wider cyber campaign, meaning observers could access CCTV feeds and track military imports and supplies into Ukraine.

A ‘Joint Cyber Security Advisory’ released by security agencies from approximately 20 western states described the campaign as ‘Russian-state sponsored’ and linked it to the GRU.

In August, pro-Russian cyber attackers opened a dam in Bremanger in Norway, releasing 500 litres of water per second for four hours.

“The aim of this type of operation is to influence and to cause fear and chaos among the general population,” a senior Norwegian intelligence official said, adding “our Russian neighbour has become more dangerous.”

The Russian embassy in Oslo said the comments were “unfounded and politically motivated”.

In November, an explosion on a Polish train line used to send supplies to Ukraine was described as an act of sabotage by Prime Minister Donald Tusk. He did not attribute blame, but Poland has pointed at Russia for dozens of acts of sabotage on its territory.

Finland too has found itself straining to deal with its fair share of incidents, ranging from undersea cable breakages, to cyber attacks, to those of an untypical nature.

“A bit more than two years ago, Russia pushed around 1,300 people of several nationalities across the border,” Jarmo Lindberg, a retired general and the country’s former Chief of Defence, told Prime Time.

“They gave them bikes because you can’t cross the border on foot, so you have to have a vehicle. They gave them bikes and they took their passports and money away and then pushed them to the Finnish border.”

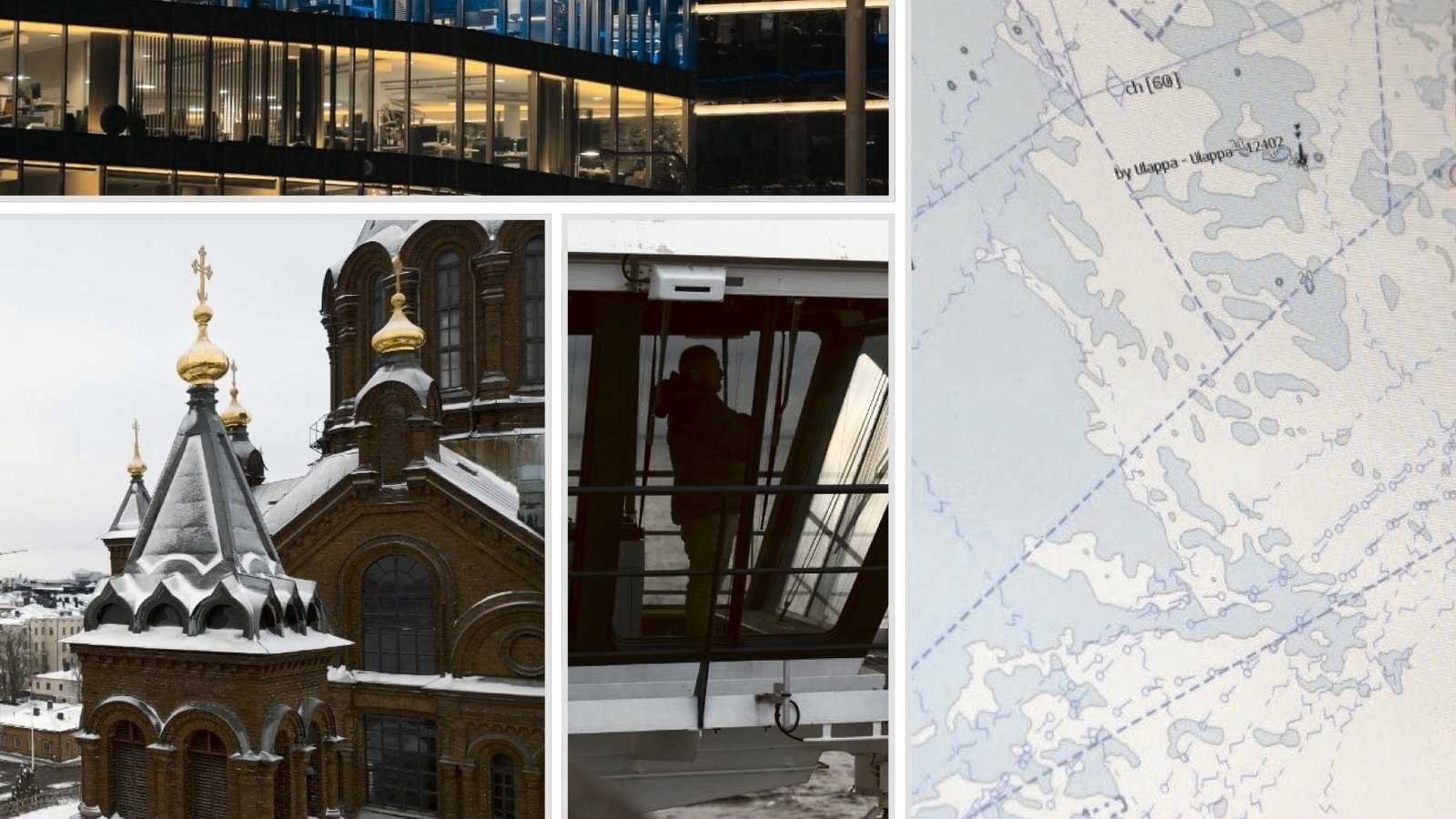

Helsinki is home to the European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats

Finland closed its border crossings with Russia in the wake of this incident and they have remained closed since.

Finns have also been dealing with an increased amount of GPS interference; there were 2,800 incidents of GPS jamming in 2024, up from just a couple of hundred in the previous year.

On New Year’s Eve, authorities detained a ship and its crew after yet another undersea cable was severed beneath the Gulf of Finland.

Perhaps for good reasons, Helsinki is home to the European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats. Its director Dr Teija Tiilikainen said that while her view is the current situation does not meet the definition for war, “we are in a serious conflict”.

She said the intention is “to weaken us, our unity, our possibilities to protect our societies, our democracy, our democratic values. This is how it goes.”

Regardless, the country appears prepared for war, conventional and unconventional.

In a quayside tavern in Helsinki’s port, a woman enjoying a post-work glass of wine tells us that in the event of an invasion she will be reporting to a shelter near her home and immediately starting work as an administrator. A man said that if war breaks out, his father has been tasked with blowing up a bridge close to where he lives.

Dr Teija Tiilikainen said that ‘a lot of harm can be caused to societies’

These are preparations for bombardment, invasion, boots on the ground. Yet the question for Finland now, and for many in the rest of us in Europe, is increasingly how to handle hybrid threats.

The answer is not a straightforward one, but Dr Tiilikainen said that is being taken “extremely seriously”.

“A lot of harm can be caused to societies. Entire societies can be paralysed if there are well-planned attacks, for instance, against critical infrastructures,” she said.

Jarmo Lindberg, the former Chief of Defence, has spent the last three years as a member of parliament. He said that while attributing hybrid events is difficult, there are many cases about which there is little doubt.

“We know it’s Russia who’s pushing the people across the border, and we know that it’s Russia who’s jamming the GPS signal” he said.

“When there have been so many incidents throughout the years, then people are concerned. And also people are asking the government officials and politicians that, ‘what are we going to do about it?’”

“We’re not at war”, he said, “but it’s not peace either. It’s something in between.”

A special report on hybrid warfare by Conor Wilson and producer Isabel Perceval will be broadcast on the 3 February edition of Prime Time, on RTÉ One and the RTÉ Player