Key Takeaways:

- Universities and companies are making devices inspired by biology and the human senses to help with health monitoring, semiconductor materials development, human-computer interfaces, and more.

- When this nascent technology becomes a viable product, government regulations will be needed to ensure consumer safety in tracking or treating their body and the environment.

- Quantum is a multiplier when it comes to experimentation in the medical space, particularly for drug and materials discovery.

Amazing developments are occurring in the bio-medical space, where new types of devices made of unusual materials and gels can measure tiny lab-grown brain cells, and sensors can measure every environmental and bodily function, from blood to heart and everything in between.

Together, these devices are going to offer a ton of data to companies, researchers, and — eventually, maybe, consumers — that can be used to investigate what is happening in the body and our world to a degree never before possible.

Among biomedical device and materials advances:

- Pennsylvania State University researchers found borophene may be better than graphene for advanced sensors and implantable medical devices.

- Penn State scientists created patchy nanoparticle-based thermogel materials, with potential for development of next-gen biomedical materials.

- University of Nebraska–Lincoln engineers took a systems-level approach for a soft robotics technology that can identify damage from a puncture or extreme pressure, pinpoint its location, and autonomously initiate self-repair.

- University of Massachusetts Amherst engineers created an artificial neuron with electrical functions that closely mirror those of biological ones, with potential for immensely efficient computers built on biological principles which could interface directly with living cells.

- Michigan State University researchers developed a way to grow crystals using laser pulses, for technologies such as medical imaging.

- University of Hong Kong, University of Cambridge, and University of Chicago researchers designed hydrogel-based 3D transistors that can mimic the behavior and structure of neurons in the human brain.

- University of Chicago Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering researchers discovered a hydrogel semiconductor that can create better brain-machine interfaces, biosensors, and pacemakers.

- University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign researchers developed a bioinspired approach to the rapid printing of fine fibers in gel, in pursuit of fine microstructures that cannot be realized using conventional semiconductor manufacturing techniques.

- Harvard University researchers developed a way to program liquid crystal elastomers with the ability to deform in opposite directions just by heating, for applications such as smart textiles or temperature-regulating robotic skins.

- Harvard bioengineers developed a soft, thin, stretchable bioelectronic device that can be implanted into a tadpole embryo’s neural plate.

- EPFL researchers developed a neural recording device called the “e-Flower” that gently wraps organoids in soft petals.

- imec and NeuroGyn, founded by Dr. Marc Possover of the University of Aarhus, developed PosStim, a neurostimulator for pelvic nerve disorders.

Challenges in consumer deployment and adoption

One of the most infamous examples of putting sensor technology in the hands of consumers is Theranos, which claimed to have created a blood-testing device capable of running hundreds of tests from a single drop of blood. Could a successful company do this next?

“What made Theranos not real was their assumption that blood was a homogeneous liquid and you could just dilute it down, and you get the same answer,” said David Fromm, COO at Promex. “Blood is the challenge, but there are several new companies that have very reliable technology, and they’re making it. Treatment has been run for the last 20 years in hospital, in pathology settings, and they’re pushing that to the point of care. Put a nasal swab in their consumable, put the consumable in a machine, and get an answer that says you have the flu or strep or covid with molecular tests, those are real.”

There are three main challenges to getting unlimited environmental and biometric data into consumers’ hands. “Compute, the sensors, and regulations,” said John Weil, vice president and general manager for IoT and edge AI processors at Synaptics. “The compute part is easy. MCUs offer more compute than you probably even need and can be very intelligent.”

The second problem is that sensor technology is still evolving, although many companies and researchers are working on this. The third problem is government regulation.

“Several governments in the world don’t want you to know various bits of data, so they classify it as protected knowledge,” said Weil. “The big one here in the U.S. is medical. The U.S. uses the FDA to regulate medical testing. The most sophisticated medical device you have at home is your bathroom scale, and that’s on purpose. They don’t want you using data about yourself to make a medical decision that might affect your life. The government in the U.S. isn’t the only one that does this. Now you start talking about water quality and other things. Not everybody wants everybody else to have the information.”

In general, governments want to protect consumers for their own good, rather than because they have a way to keep making money by keeping the technology out of consumers’ hands. “Take Apple’s smart watch,” said Weil. “It’s taken them years to get the EKG on your wrist, not because we as an industry didn’t know how to do it before. It took that long to get through the paperwork to get it approved. Because EKG is a protected medical thing, the government doesn’t want you using EKG to make life-altering decisions.”

A related challenge is that once people have the information that something is wrong with their body or environment, they may not have the ability to do anything about it.

“In the state of Missouri, they started a program a couple of years ago called Get The Lead Out,” said Adam Scotch, R&D director for Smart Devices at Brewer Science. “It requires every school district to monitor every school at least once a year, to measure every tap for lead, and then if it finds it, it has a certain period of time to remediate it. The lead concentration varies by tap, not by building, because of the local distribution. There are schools where every single water fountain or water source tap has elevated lead concentration — 20, 40, 50 parts per billion. There are some where it’s just one or two taps. It is such a local problem, and they didn’t know.”

The problem was that the program was unfunded. “If they measure an elevated amount of lead, they have to either shut off the tap or do remediation, and they don’t have the money for that either,” said Scotch. “Unfortunately, we see this not just in the school districts, but nobody wants to measure their water because they’re afraid that they’re going to have to take action. If they don’t measure it, then they don’t know. This is a challenge. This is going to be a dangerous area in the future. But it’s a good time to be a plumber.”

Brewer currently sells the water sensors business to business, but consumer could be next. Once people get sensors in their hands, they will start appealing to authorities to fix things.

“It’s necessary, because we’ve abandoned our water, which is our most precious natural resource,” said Scotch, who helped develop Brewer’s water sensors. “We’re always worried about oil and coal running out. There’s always concern about fossil fuels in general being depleted, or mining of precious metals, but nobody really thinks about water in quite the same way, until more recently.”

AI, the cloud, and security

Many companies are making low-power wellness and consumer connectivity devices that gather vitals and track physical activities, then use AI to assist with preventive health care. “We are building a walker that collects day-to-day activities from the user to ensure there is no unusual activity,” said Roberto Condorelli, marketing director of sensor systems for the Computing and Connectivity Business at Infineon Technologies. “When there is an aberration, the doctor is notified and contacts the user/patient to determine if there are more severe issues that need to be addressed immediately. Governmental regulators and other stakeholders play key roles in bringing more intelligence to wellness edge devices while ensuring data security and privacy for today’s consumers.”

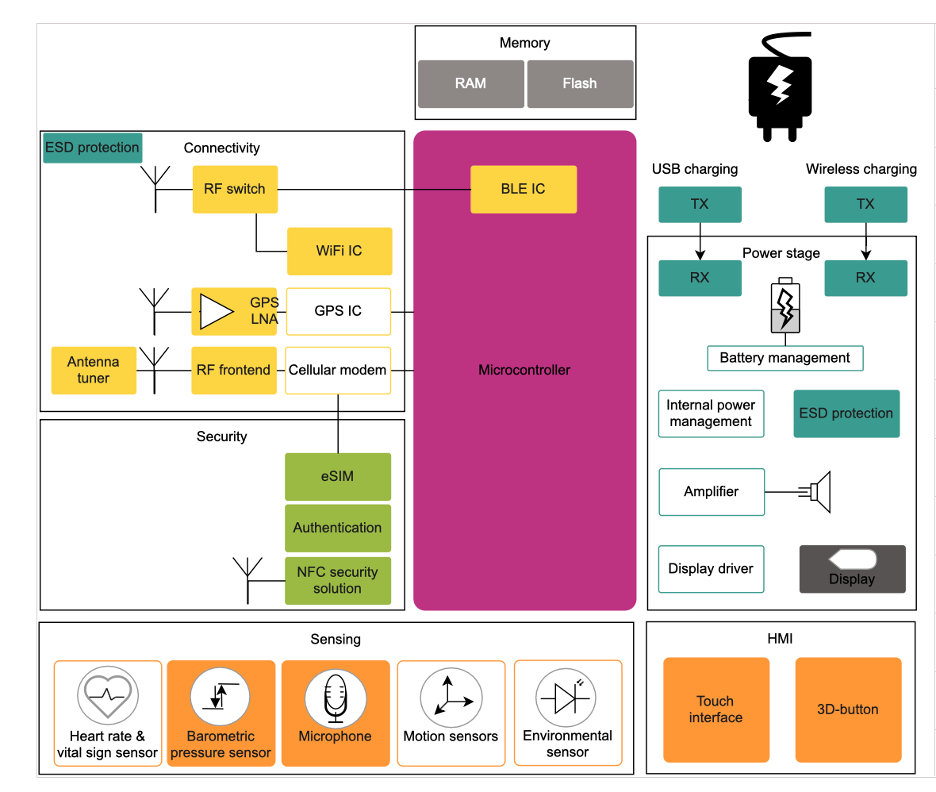

Fig. 1: A block diagram of a health wearable or disposable to monitor and deliver accurate, real-time data around-the-clock. Source: Infineon

In terms of security, regulations must be quickly adjusted for new med/consumer devices to guarantee user’s privacy. “In Europe, if someone steals my personal data on that medical device or consumer device, the company is liable under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR),” said Dana Neustadter, senior director of product management at Synopsys. “It goes beyond health care. It aligns with protecting data privacy.”

Security is the responsibility of the device makers and the regulators, but not necessarily of the consumer, Neustadter observed. “It should be transparent. If I buy a consumer device, whether it’s medical or not, it’s supposed to work and do the job. If I build a device and no one really comes after me, then I can sell anything I want, even if it’s not secure in the market. I can do it if no one tells me that I have to do otherwise.”

A regulated medical device needs to implement security features with a strong secure enclave. “It should have secure boot, tamper resistance, wireless security implemented, even supply chain tracking,” said Neustadter. “But when you think about these other medical devices from the consumer side, such as my Oura ring, or you have all sorts of blood monitors that appear overnight, they tend to have a more minimal oversight in terms of security, because they’re cost driven, they have maybe shorter lifetime cycles, often the security is done but it’s rushed. Sometimes you can modify the firmware or the software that runs on it, because the secure boot is not implemented properly. Then it may be easier to spoof or extract information.”

The medical industry has been slower to adopt cloud, partly due to concerns over security and privacy. The more data that medical devices generate, the more data there is to be stolen. “The stakes are very high for these devices,” Fromm noted. “They have some of the most intimate information you could have about people, and it seems like it’s going to be measuring everything.”

The FDA is creating guidance on how to manage the data, which is especially important now that AI/ML is pushing further into these edge devices and analyzing more data than ever before. “There’s a lot of experience and guidance that’s been happening there,” Fromm noted. “There’s a lot more infrastructure than there was a decade ago.”

Being cloud-connected does not necessarily pose a bigger risk to medical devices than to any other device, but there are different degrees of assurance needed, Neustadter noted. “If I talk about a pacemaker in someone’s body, and if that information is shared with the cloud — maybe the doctor wants to remotely monitor and regulate it or change some of the settings of that pacemaker — then we’re talking about someone’s life,” she said. “With that category of devices, the security protection is fundamental. The protection against failure has to be the highest, but then you may have other devices, like a blood glucose monitor, that’s not as critical as a pacemaker. Regardless, when you connect to the cloud, the communication needs to be the highest grade security. Then the data in the cloud needs to be protected, and usually the cloud infrastructure already has a lot of such mechanisms.”

Neuro developments

Brewer Science’s flexible, printed water quality sensors evolved out of long-term research into possible use cases for carbon nanotubes. Accidental discoveries like this are not uncommon in the sensor and biomedical space. Another case of happenstance led to the development of a flexible device to monitor the electrical activity of neural spheroids, which are 3D clusters of neurons that replicate some of the key functions of brain tissue.

“In our lab, we work on implants for the brain, in a very broad sense,” said Eleonora Martinelli, PhD candidate at the Laboratory for Soft Bioelectronic Interfaces at EPFL. “I don’t work on devices for the brain, but for these brain mimics called brain organoids and spheroids. My colleague Outman [Akouissi] was working on implants for the brain and for spine peripheral nerves. If you reduce the stiffness of the implant to get closer to the stiffness of the tissue — which are not stiff at all, they’re very soft — then you reduce the foreign body reaction. You reduce the reaction that your body has against the implant that you are inserting. Outman, in his work, was looking at using hydrogels as coatings for flexible implants, to see if this could be used as a solution to reduce the foreign body reaction in the human body. He had a lot of flexible implants that he was coating with these hydrogels. At that point he noticed that the implants would curl due to the swelling of the hydrogel. In his case, this curling was not wanted, because he wanted to insert the implant inside the nerve, transversal to the nerve itself. For that, it’s very important to keep the location of the electrodes very precise, so having this uncontrolled curling was something he didn’t want to have in his implant.”

It was at this point that Martinelli joined the lab. “I was working on brain organoids and spheroids,” she said. “One of the challenges in the field was to obtain another implant, a microelectrode array, that could envelop such tissues. In order to do that, you need a mechanical actuation mechanism. At that point, the idea was, why don’t we use this combination between the flexible implant and the hydrogel to actuate our implant around the surface of the brain organoid or spheroid? This is basically how everything started. In the end, Outman did not continue using the hydrogels in his main project, the initial one, but we shifted completely to using them for the spheroids.”

The resultant device is an e-Flower, which is designed to be compatible with existing electrophysiological systems, offering a plug-and-play solution for researchers that bypasses complex external actuators or harmful solvents. Once applied to organoids,

the technology can record electrical activity from all around the brain-like cells to help understand brain processes and assist in areas such as drug discovery.

The role of quantum

High-performance computing and quantum technology are being used to speed up materials and drug discovery, with huge implications for engineering, biology and medicine.

“The rate of innovation into this field has really made quantum the landscape in 2025 not a stay tuned, but hurry up and listen,” said Rajeeb Hazra, CEO of Quantinuum, speaking at Infineon’s OktoberTech event. “It’s not so much just the companies that are taking this very seriously in terms of betting their next generation strategic infrastructure on quantum computing being there, but also the breadth of the markets. Finance, transportation, energy, pharma, sustainability, materials, cyber. If you look at some of the use cases — I could spend hours talking about it, don’t worry, I won’t — these are transformational to businesses.”

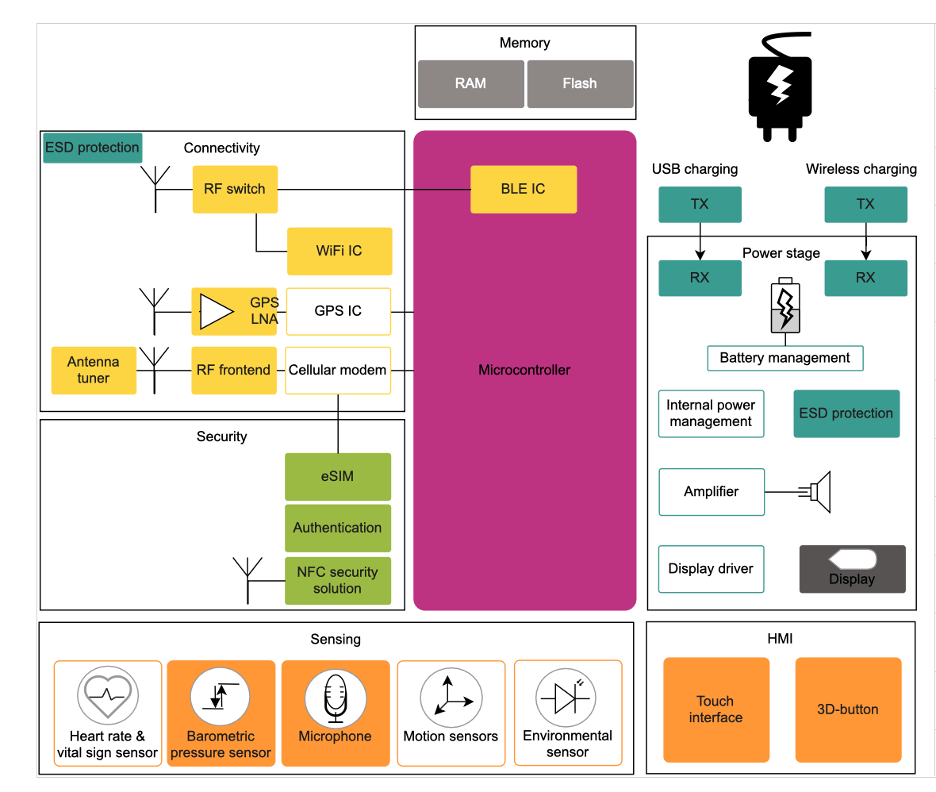

Fig. 2: Quantum and GenAI can create breakthroughs in drug discovery and quantum topological data analysis in areas such as health. Source: Semiconductor Engineering/Quantinuum at Infineon’s OktoberTech

This is not about the next 10% or 15% of efficiency, which is important at scale. It’s about fundamentally recharging and rejuvenating the process of discovery. “How do you create the next material that absorbs carbon dioxide in the atmosphere more effectively and more efficiently than you do today?” asks Hazra. “Or the creation of new materials that you see when it says ‘long acting’ on the side of the box for Tylenol, for instance, that it is truly long acting — not as a guess of how fast some object dissolves in your body, but actually goes to the spot and then crumbles, if you will, to deliver the medicine of very tight kinematic control to the pathology. These are the things that quantum computing revolutionizes in a way that it’s not just about more and more and faster and cheaper. I hate to say this as an old semi guy, but it’s not about Moore’s Law anymore. It is about an architectural breakthrough that is more to the power of more. We stand at an amazing point in time where we have this thing called AI.”

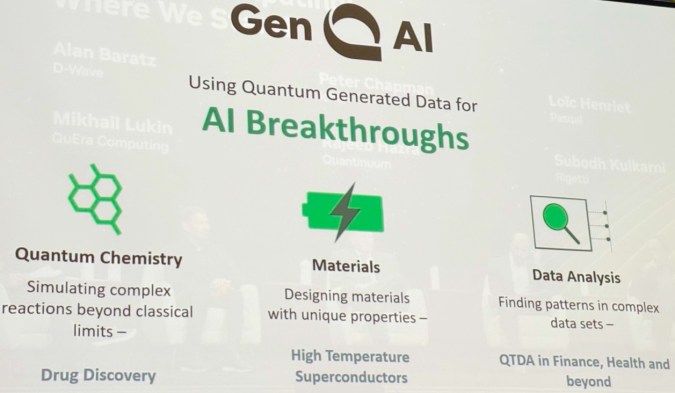

Fig. 3: Quantum eras from now until 2029. Source: Semiconductor Engineering/Quantinuum at Infineon’s OktoberTech

Conclusion

Researchers and engineers are working on sensors and devices to learn more about the human brain, the body, and everywhere in the environment we breathe, drink, eat, and touch. Consumers have a desire to learn and monitor more for themselves, without doctors and corporations serving as middlemen. But here are risks to a do-it-yourself approach, and governments are proceeding cautiously.

Selected Technical Papers

- Apple: “Foundation Model Hidden Representations for Heart Rate Estimation from Auscultation.”

- Kyungpook National University in South Korea, and others: “High-Resolution Mechanoluminescent Haptic Sensor via Dual-Functional Chromatic Filtration by a Conjugated Polymer Shell.”

- Meta Reality Labs: “A generic non-invasive neuromotor interface for human-computer interaction.”

- Osaka University: “Information Processing via Human Soft Tissue: Soft Tissue Reservoir Computing.”

Related Reading

Environmental Sensors Catch More Data For A Greener World

New types of sensors can generate environmental data in real time using a range of tools, including flexible, printed ICs and AI/ML.

Wearable Connectivity, AI Enable New Use Cases

New types of wearables and devices can record bodily data or simulate the senses without needing to meet stringent med-tech rules.