The light of a soft winter sun illuminates the faces of two very different women.

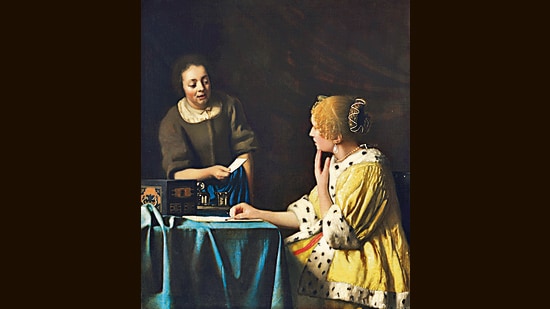

PREMIUM Mistress and Maid (1664-1667) (The Frick Collection, New York/Joseph Coscia Jr.)

PREMIUM Mistress and Maid (1664-1667) (The Frick Collection, New York/Joseph Coscia Jr.)

One leans over a desk, writing a letter. The other, her maid, looks toward the window with an air of mild impatience. The light streaming in through a window picks out tiny details in this scene of seemingly mundane domesticity: a quietly chaotic painting on a wall, a piece of discarded parchment on the floor.

Painted between 1670 and 1672, Woman Writing a Letter with Her Maid is one of three epistolary works displayed side-by-side at The Frick Collection in New York, in its first show after a major, five-year renovation.

All three works are by the Dutch master Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675), known best for A Girl with a Pearl Earring (1665). Vermeer died aged just 43, bankrupt and in a state of penury. Only 37 of his paintings survive. Most depict scenes of serene domesticity. We’ll get to why that’s ironic in a bit.

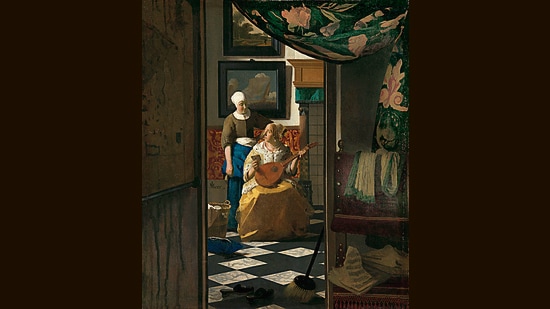

First, the three paintings. In addition to Woman Writing a Letter…, there is Mistress and Maid (1664-1667), showing a woman mid-scribble, wearing a perplexed expression, as her maid hands her a folded-up note; and The Love Letter (1669-70), in which a timid-looking woman pauses her playing of a stringed instrument to take a written missive from the rather triumphant-looking help.

The Frick museum went to great pains to bring these works together. Two were shipped, on loan, from Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam and the National Gallery of Ireland in Dublin.

Here’s why they went to all that trouble: sitting side-by-side, the paintings constitute a rare view of domesticity in 17th-century Denmark. One sees here how Vermeer used women as his primary protagonists, and how he placed those of different social classes on an equal footing, turning them into the shared focus of each work (an approach that was unusual for his time; maids, for instance, were usually relegated to corners and backgrounds).

Letters were a way to explore something of these women’s shared inner lives.

They were often used in art of the time, to inject emotion and interaction into a still life, says Robert Fucci, an art history scholar and lecturer at University of Amsterdam and curator of the exhibition.

“The depiction of the ‘internal’ was seen as a great challenge for painters,” he adds. “Letters offered them a chance to reflect on mental activity and emotional responses.”

The Love Letter (1669-1670). These works offer a rare view of domesticity in 17th century Denmark. (Rjiksmuseum, Amsterdam)

The Love Letter (1669-1670). These works offer a rare view of domesticity in 17th century Denmark. (Rjiksmuseum, Amsterdam)

A canvas of contrasts

Now to the matter of Vermeer and peaceful domesticity.

The artist was born to Reynier Vermeer, a textile trader and a successful art dealer. By 1641, the family is said to have been prosperous enough to acquire an inn in the Delft market square.

Vermeer inherited both businesses after his father’s death, and ran them successful, for a time, during the country’s Golden Age. This was a period when the Dutch empire was growing, and the country becoming increasingly prosperous.

Vermeer was, by this time, a highly respected artist himself, serving more than once as head of the painters’ guild. Still, his art was not widely collected in his time. For one thing, he was not prolific, says Fucci. For another, “a primary patron appears to have snapped up many if not most of his works, leaving him with little visibility in a booming art market.”

At 21, meanwhile, he fell in love with and married Catharina Bolnes, converting from Protestantism to Catholicism for her. By 1969, the 37-year-old and his wife were raising 11 children together.

Then came the Rampjaar or “Disaster Year” of 1672.

The Dutch economy was faltering, a condition made worse by the six-year Franco-Dutch war. The art market was one of a number of luxury segments that collapsed. Left with piles of art that now wouldn’t sell, Vermeer was ruined. He borrowed money, leveraging property as surety. In a note to his creditors after his death, Bolnes wrote of the toll his financial burdens had taken. “In a day and a half he went from being healthy to being dead,” she said.

The family was so penniless by this time that Bolnes gave two of the three paintings in the Frick show (The Love Letter and Woman Writing a Letter with Her Maid) to the local baker in an effort to clear her debt with him, on condition that he would allow her to buy them back one day. She does not appear to have gained them back at any point.

Both were recent works. Through his life, Vermeer had continued to paint his scenes of quiet domesticity, placing himself and his viewer in simpler times.