Navigate to:

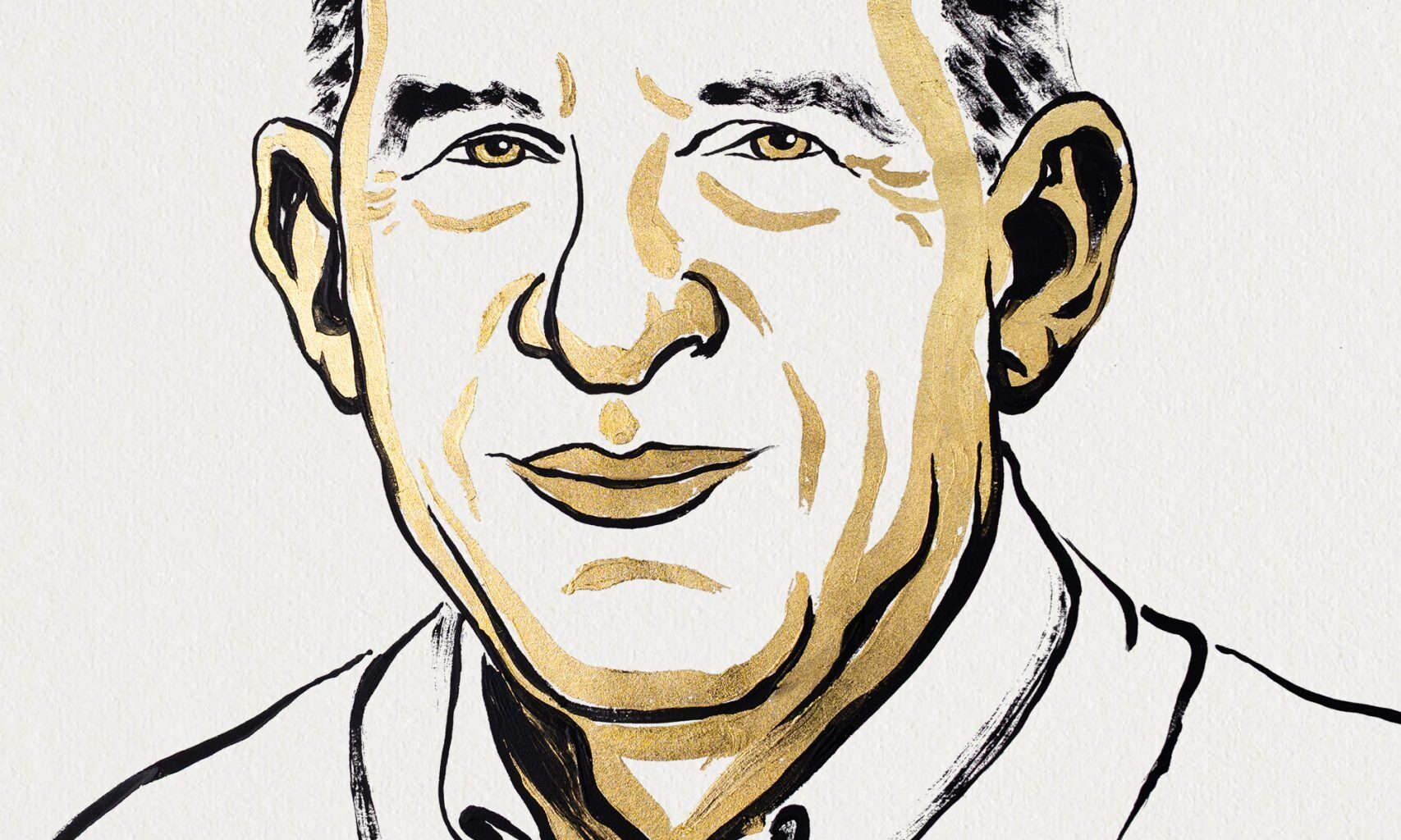

Summary- John Clarke– Facts– Interview– Photo gallery– Other resources- John M. Martinis Prize announcement Press release Advanced information Popular information

First reactions. Telephone interview, October 2025

“I would say a fundamental discovery really becomes true when you can apply it to something concrete.”

Michel Devoret reflects on the excitement of seeing the fruits of research. He also talks about his co-laureate John Clarke, one of his role models, together with Lord Kelvin. Devoret describes how he woke on announcement day to find that the world already knew the news: “I had completely forgotten that October was the Nobel Prize month!”

Transcript

Michel Devoret: Yes, hello.

Adam Smith: Hello, this is Adam Smith calling from the website of the Nobel Prize. Am I speaking to Michel Devoret?

MD: Yes, unfortunately there’s a conflict. There is an organisation, the nobelprize.org, and that was maybe a confusion.

AS: No, that’s me. I’m the one calling from nobelprize.org.

MD: There’s been a little confusion.

AS: It’s been a confusing week, generally, and it must have been a very confusing two days for you.

MD: Well, I guess it has been like when you received the Nobel Prize.

AS: Yeah, that pretty much sums it up, I agree. How did the news actually reach you?

MD: When I woke up at 7am California time on Tuesday, and there was a lot of activities on my cell phone and on my computer, but I thought it was a joke. I didn’t take it too seriously, and then it seemed intense. So just to be sure, I called my daughter who is living in Paris, so she’s nine hours ahead of me, and I was able to then see that this was for real.

AS: Yes, she had had some time to live with the news for a while.

MD: Exactly, exactly. Plus, I had completely forgotten that October was Nobel Prize month.

AS: Completely unprepared.

MD: Yes, completely unprepared. And you know, some physicists may feel some anxiety at the beginning of October, but that was absolutely not the state of mind at all.

AS: Luckily, you had a proper night’s sleep before you had to confront the press, so you were well prepared.

MD: Yes, the same. A similar story happened to John Martinis, whose wife did not wake him up, as I’m sure you…

AS: Yes, indeed, he told us it was so generous of her to take all the flack herself for a few hours. Indeed, John Martinis and John Clarke have both spoken so warmly of that time 40 years ago when you were working together in the lab in Berkeley, and how there was such a lovely interchange of ideas between the three of you. How do you remember those years, -82 to -84?

MD: Yes, I have similar memories. These are very, very fond memories of this work in the lab, working on a fundamental question of physics in a way that was totally free. We could mull over what the experiment was meaning, and it was marvellous.

AS: And it’s interesting that, well, all three of you from different places, but you end up working on the west coast of the US, and indeed, I think six out of nine of the scientists announced this week, who’ve been awarded the Nobel Prize, have ended up working on the west coast. What is it about the environment that makes it so productive, do you think?

MD: Well, the west coast of the United States has been described by a friend on the east coast a long time ago as the America of America. I think that’s a good short description. It’s doubly American in some sense, and there’s still a marvellous sense of adventure, and also Berkeley is a lovely university, extremely well placed on the Pacific coast with marvellous views of the Golden Gate. This is a wonderful environment, of course.

AS: Yeah, indeed. And you’ve worked in different places, and you like to work on grand challenges. Now you find yourself as chief scientist at Google Quantum AI. What sort of challenge attracts you? What sort of problem do you like to get to grips with?

MD: Well, you see, so we were lucky 40 years ago to be able to work on a very fundamental problem, a very fundamental question that is at the heart of the formulation of quantum mechanics. But very luckily for us, our initial discovery was developed by many labs around the world. This became bigger than us in some sense, this whole work, international work on quantum superconducting circuit. And Google recently has been in the front line for creating quantum superconducting circuit with which you could start to do quantum computing, and in particular quantum error correction, which is essential in the building up of large-scale quantum computers. So this is what has attracted me to work at Google. They were developing these circuits for quantum computation. Actually, as you know, John had the vision that these circuits could be scaled up. And in some sense, he’s part of the foundation at Google of their work on quantum computation.

AS: It’s extraordinary to observe the development. It takes time though. It takes time.

MD: Yes, I think we can say that indeed from an initial discovery to the start of an industry, you see you have many decades.

AS: Yeah, it’s an extraordinary thing to witness and be involved in. Are you surprised by your own evolution from fundamental questions now to attempted application?

MD: I think really, I would say that a fundamental discovery really becomes true when actually you can apply it to something concrete. You know, I’ve been inspired by other scientists, and particularly those who were able to conduct both fundamental research and applied research at the same time. So my model was actually John Clarke. I joined this laboratory because I was, you know, extremely impressed by the fact that he was conducting fundamental research on superconductivity, but he was also working on SQUIDs, which are sensing devices with many, many applications. This combination of fundamental research and application. We have a glorious predecessor, Lord Kelvin, one of the founding fathers of thermodynamics, he played also an immense role in electromagnetism. He was part of a company that created this telegraphic line between the United States and England, this transatlantic telegraphic line. So he had this activity both in very fundamental science, but at the same time, really, it’s quite obvious that he participated into a large scale industrial application of electricity.

AS: It’s fascinating to look back at those who have trod the path before and to make the comparison, very interesting. So how much of a disruption is all of this going to be to your work?

MD: Well, it’s a disruption, but at the same time, it will allow me to speak to young students and do my share in essentially, speaking for the interest of science and give back in some sense, because I have myself been very impressed by scientists who were able to explain their work in simple and clear terms.

AS: It is wonderful to hear you say that you want to give back to young scientists and engage with them.

MD: We learn science at school, but it resonates completely when you see a scientist, you really see the freedom and independence of mind that is not always apparent in school programs.

AS: The personification of great science is so much more approachable than the dry textbook. It’s been a huge pleasure speaking to you and I wish you a relaxing and wonderful weekend when it comes.

MD: Yes, thank you very much.

AS: Thank you.

To cite this section

MLA style: Michel H. Devoret – Interview. NobelPrize.org. Nobel Prize Outreach 2025. Wed. 22 Oct 2025.

Back To Top

Takes users back to the top of the page