Dark matter near the center of our galaxy is “flattened,” not round as previously thought, new simulations reveal. The discovery may point to the origin of a mysterious high-energy glow that has puzzled astronomers for more than a decade, although more research is needed to rule out other theories.

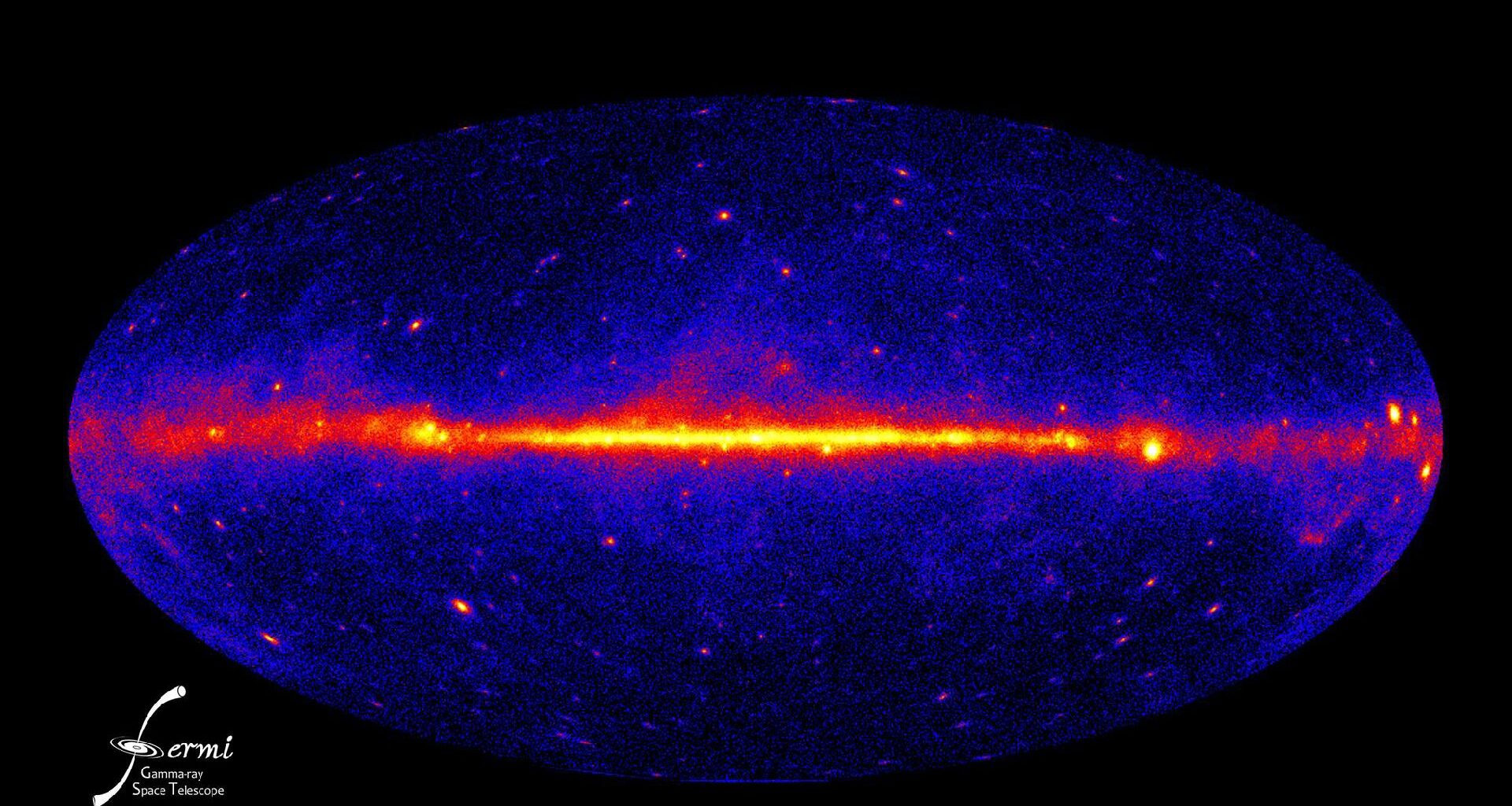

“When the Fermi space telescope pointed to the galactic center, it measured too many gamma rays,” Moorits Mihkel Muru, a researcher at the Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam in Germany and the University of Tartu in Estonia, told Live Science via email. “Different theories compete to explain what could be producing that excess, but nobody has the definitive answer yet.”

Early on, scientists proposed that the glow might come from dark matter particles colliding and annihilating each other. However, the signal’s flattened shape didn’t match the spherical halos assumed in most dark matter models. That discrepancy led many scientists to favor an alternative explanation involving millisecond pulsars — ancient, fast-spinning neutron stars that emit gamma-rays.

You may like

Now, a study published Oct. 16 in the journal Physical Review Letters and led by Muru challenges the long-standing assumption about the shape of dark matter. Using advanced simulations of the Milky Way, Muru and his colleagues found that dark matter near the galactic center is not perfectly round, but flattened — just like the observed gamma-ray signal.

A persistent cosmic puzzle

Gamma-rays are the most energetic form of light. They are often produced in the universe’s most extreme environments, such as violent stellar explosions and matter swirling around black holes. Yet even after accounting for known sources, astronomers have consistently found an unexplained glow coming from the Milky Way‘s core.

One proposed explanation is that the radiation originates from dark matter — the invisible substance that makes up most of the universe’s mass. Some models suggest that dark matter particles can occasionally smash together, converting part of their mass into bursts of gamma-rays.

“As there are no direct measurements of dark matter, we don’t know a lot about it,” Muru said. “One theory is that dark matter particles can interact with each other and annihilate. When two particles collide, they release energy as high-energy radiation.”

But this theory fell out of favor when the flattened, disk-like shape of the gamma rays failed to match up with the hypothesized shape of dark matter haloes — which are thought to be spherical.

Astronomers suspect that many galaxies, including the Milky Way and NGC 24 (shown here), are contained within extended, spherical haloes of invisible dark matter. (Image credit: NASA / Hubble)Rethinking the shape of dark matter

Muru and his colleagues set out to revisit the basic assumption that dark matter in the inner galaxy must be spherical. Using high-resolution computer simulations known as the HESTIA suite, which re-creates Milky Way-like galaxies within a realistic cosmic environment, the team studied how dark matter behaves near the galactic center.

They found that past mergers and gravitational interactions can distort the distribution of dark matter, flattening it into an oval or box-like shape — much like the bulge of stars seen in the middle of our galaxy.

You may like

“Our most important result was showing that a reason why the dark matter interpretation was disfavored came from a simple assumption,” Muru said. “We found that dark matter near the center is not spherical — it’s flattened. This brings us a step closer to revealing what dark matter really is, using clues coming from the heart of our galaxy.”

This revised picture means that the pattern of gamma-rays expected from dark matter annihilation could naturally look very similar to what astronomers observe. In other words, the dark matter explanation might have been underestimated simply because scientists were using the wrong shape.

What comes next

Although the new findings strengthen the case for dark matter as the origin of the gamma-ray signal, they don’t close the debate. To distinguish between dark matter and pulsars, astronomers need sharper observations.

“A clear indication for the stellar explanation would be the discovery of enough pulsars to account for the gamma-ray glow,” Muru said. “New telescopes with higher resolution are already being built, which could help settle this question.”

If upcoming instruments, such as the Square Kilometre Array (SKA) and the Cherenkov Telescope Array (CTA), reveal many tiny, point-like sources at the galactic center, it would favor the pulsar explanation. If, instead, the radiation remains smooth and diffuse, the dark matter scenario would gain support.

“A ‘smoking gun’ for dark matter would be a signal that matches theoretical predictions precisely,” Muru noted, adding that such a confirmation will require both improved modeling and better telescopes. “Even before the next generation of observations, our models and predictions are steadily improving. One future outlook is to find other places to test our theories, such as the central regions of nearby dwarf galaxies.”

The mystery of the gamma-ray excess has endured for more than 10 years, with each new study adding a piece to the puzzle. Whether the glow comes from dark matter, pulsars or something entirely unexpected, Muru’s results highlight how the galaxy’s structure itself may hold vital clues. By reshaping our understanding of the Milky Way’s dark core, scientists are inching closer to answering one of the most profound questions in modern astrophysics — what dark matter really is.