Norway is extending its Northern Lights project to include 5,000,000 tons of carbon dioxide undersea storage, storing emissions below the seabed rather than above the atmosphere. Whether this is bold or reckless, it could change the climate trajectory for Norway. Is this a real step towards decarbonisation, or a reckless abandonment of fossil usage, or a desperate attempt?

Diving into the details of Norway’s top project, taking the world by storm

For many years, the source of Norway’s wealth was the oil and gas that drove much of Europe. Now, however, the offshore expertise that has drilled for fossil fuels is being repurposed to store carbon dioxide instead of hydrocarbons.

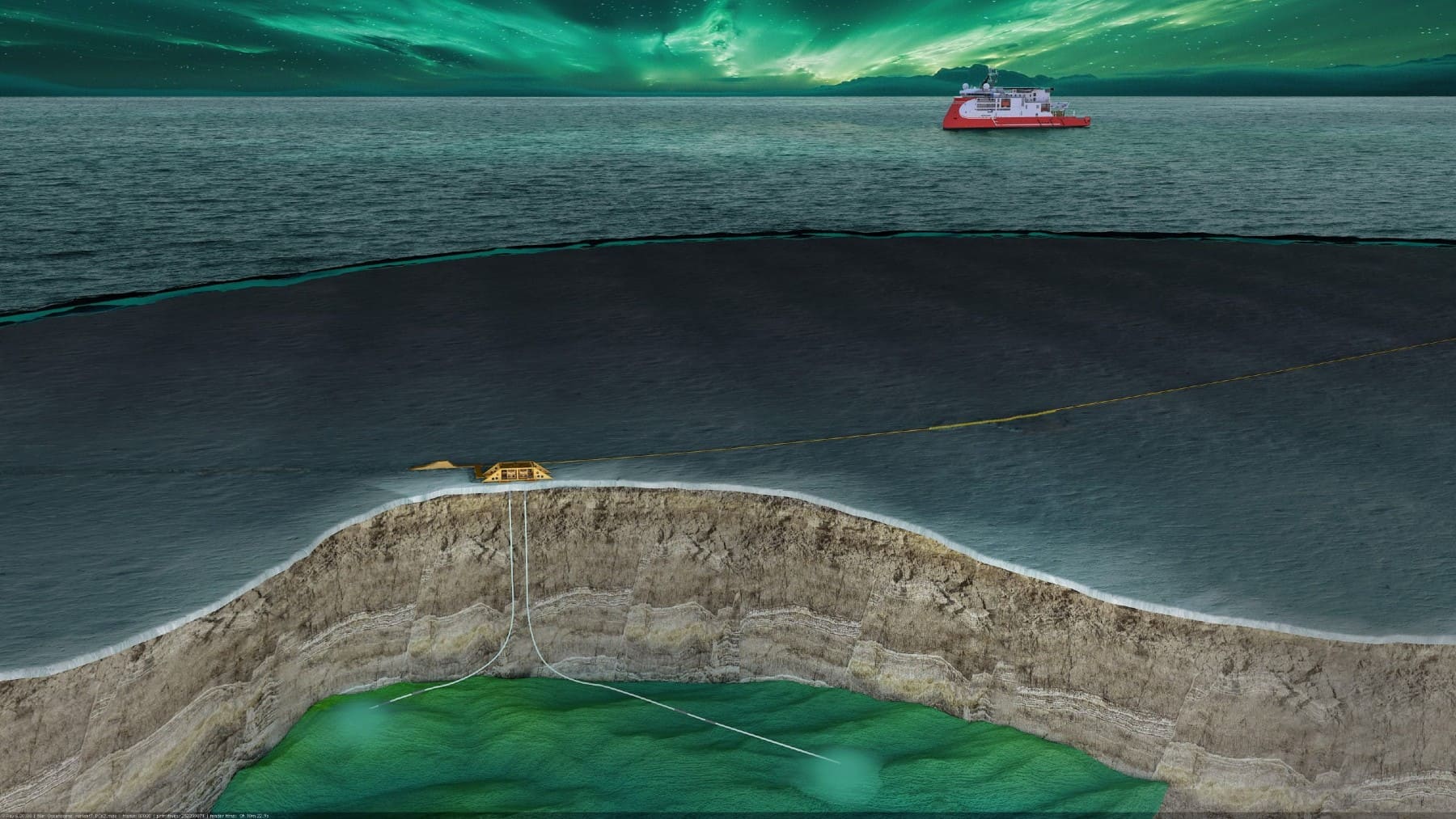

At the center of the transition is Northern Lights, the world’s first commercially viable open-access carbon dioxide transport and storage network. It is part of Norway’s state-funded Longship CCS initiative, which is designed to capture CO2 from the various industrial sites across Europe, liquefy the carbon dioxide, ship it to the Norwegian coast, and store it permanently 2,600 meters underneath the North Sea.

Phase 1, which is already in operation, traps about 1.5 million tons of CO2 per annum, equivalent to removing 750,000 cars annually. Nevertheless, Phase 2 is the time when the actual progress is made since it not only satisfies the ambitions of Norway but also invests in the future of the carbon market in the world.

Phase 2: Norway, 5 million tons of CO2 undersea storage, a deeper dive into what comes next

The next phase, which was announced in 2025, will expand Norway’s sub-seabed capacity for storing CO2 from 1.5 to a minimum of five million tons per annum. This phase will involve the construction of new injection wells, larger above-ground storage tanks at the Øygarden terminal, and enhanced shipping capacity for more frequent deliveries by emitters from across Europe

By 2028, the project is supposed to scale up, and it should enable companies based in Germany, the Netherlands, and possibly Poland to transport their CO2 emissions to Norway, where they can be permanently stored and used undersea, just like the underground salvation silent tank.

How the undersea storage process works to keep CO2 locked safely beneath the seabed

The procedure is complicated, albeit beautiful. Emitted CO2 is liquefied and transported to the Øygarden terminal in western Norway. From there, it is sent via a 100-kilometre-long pipeline to an offshore injection site. Two wells, soon to become four, inject a mixture of CO2 deep into the saline aquifers, where it is sealed under a bed of impermeable rock.

The movement of the injected CO2 and the pressure monitoring are now observed and verified through ever-improved sensor systems and satellites, ensuring CO2 remains sealed for long periods of time. What brought in the economic activity is now locking the climate hazard down.

Exploring the risks, the challenges, and broader climate implications

Norway’s project has obvious benefits. It supports sectors that have been slower to decarbonize, capitalizes on the country’s expertise in oilfields, and may start an entirely new green industry, generating jobs and promoting global leadership on climate.

Addressing the challenges, carbon capture and storage processes face high cost, and capturing 5 million tons annually has little effect in relation to Europe’s total emissions. Critics caution that carbon capture and storage alternatives may postpone serious transformations away from fossil fuels, while environmental groups are concerned about leakage and the long-term stability of storage sites.

Nevertheless, as a global standard-setter, Norway’s venture of putting 5 million tons of CO2 under the sea is notable and is an experiment. It serves as an example of a fossil-fuel nation actually taking climate change seriously while exploring whether it can be scaled. It will not alleviate the climate crisis, but it is a useful step towards a plausible future, just like this groundbreaking Arab’s clean energy leap.

Disclaimer: Our coverage of events affecting companies is purely informative and descriptive. Under no circumstances does it seek to promote an opinion or create a trend, nor can it be taken as investment advice or a recommendation of any kind.