Only around a third of the latest country climate pledges submitted to the UN express support for the “transition away from fossil fuels”, according to Carbon Brief analysis.

Several countries even have used their 2035 climate plans to commit to increasing the production or use of fossil fuels, predominately gas, the analysis finds.

The first global stocktake of progress to tackle climate change, agreed at the COP28 climate summit in Dubai in 2023, calls on all countries to contribute to “transitioning away from fossil fuels”.

Countries were meant to explain how they are implementing the outcomes of the global stocktake, including their contribution to transitioning away from fossil fuels, in their latest climate plans.

However, just 23 of the 63 plans submitted to the UN so far express support for “transitioning away from fossil fuels”, or the “phase out” or “phase down” of their use.

In addition, six countries, including Russia, Nigeria and Morocco, use their climate plans to commit to boosting gas production.

Some two-thirds of countries have not yet announced or submitted their pledges, missing not only the UN deadline of 10 February, but also an extension to September.

How to address the lack of sufficient action from countries with their latest plans is billed to be one of the major issues up for debate at the COP30 climate summit in Brazil next month.

Taking stock

In 2015, countries forged the Paris Agreement, the landmark deal to keep temperature rise “well-below” 2C, with “aspirations” to limit global warming to 1.5C of warming by the end of this century.

At the time, countries’ initial pledges were not enough to put the world on track to meet the temperature targets, so they built a “ratchet mechanism” into the Paris Agreement, requiring them to keep increasing their ambition in the following years.

As part of this, countries agreed to submit new, more ambitious plans every five years detailing what they are doing to take action on climate change and adapt to its impacts. These are called “nationally determined contributions” (NDCs).

The Paris Agreement also stated that, following on from these plans, “global stocktakes” should be conducted to assess collective progress in meeting the temperature goal.

The first global stocktake concluded at the COP28 climate summit in Dubai in 2023, with countries agreeing to a new document setting out how they will respond to a lack of sufficient action to meet the Paris goals.

The two-week talks saw fierce debate about how fossil fuels – the main driver of human-caused climate change – should be referred to in this text.

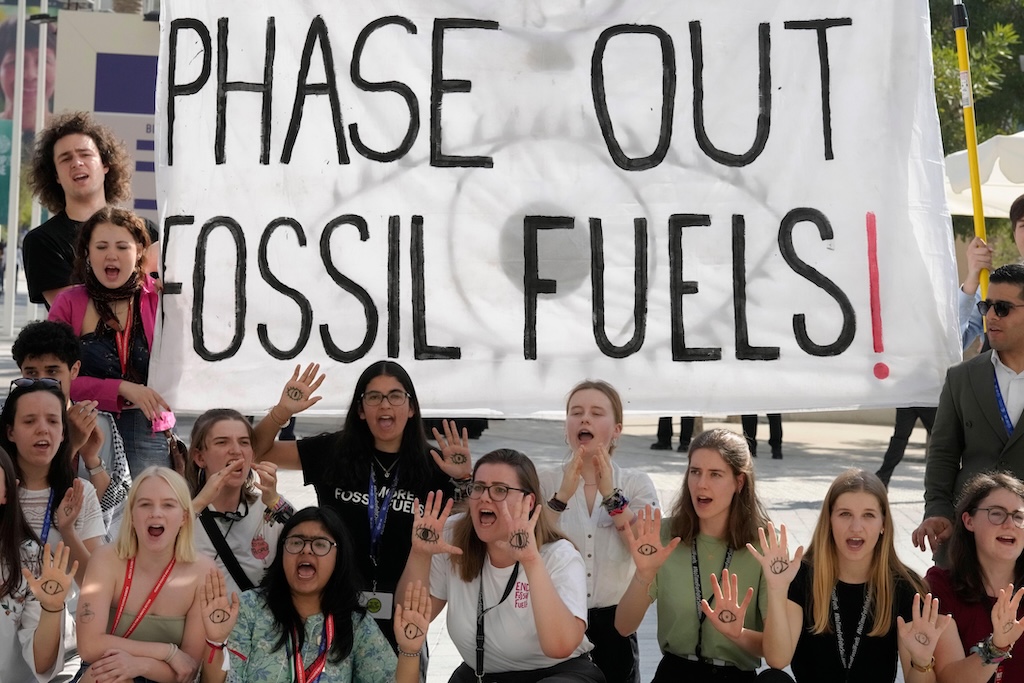

Activists demonstrating at the 2023 COP28 climate summit in Dubai Credit: Associated Press.

Activists demonstrating at the 2023 COP28 climate summit in Dubai Credit: Associated Press.

In the end, the stocktake “calls on” all countries to “contribute to” a list of global goals, including “transitioning away from fossil fuels…accelerating action in this critical decade” towards net-zero by 2050.

It was the first time that countries formally acknowledged the need to transition away from fossil fuels in almost 30 years of international climate negotiations.

However, many countries were disappointed that the text did not contain a firmer commitment to phase out all fossil fuels, or even just those with “unabated” emissions.

After Dubai, countries were expected to come up with new NDCs for 2035 that explained how they responded to the priorities set out in the stocktake.

The deadline for submitting the “3.0” NDCs was 10 February 2025, which 95% of countries missed.

On 24 September, the UN convened a climate summit in New York at the sidelines of the UN general assembly in the hope of encouraging more countries to come forward with new NDCs.

China stole the show at the event, announcing a pledge – although not yet formally submitted to the UN – to cut greenhouse gas emissions to 7-10% below peak levels by 2035. Several other countries announced new plans, including Russia, Turkey and Bangladesh.

Following the summit, around one-third of countries have announced or submitted their 2035 NDCs.

Fossil-fuel focus

For the analysis, Carbon Brief reviewed each of the NDCs submitted to the UN to determine whether they express support for “transitioning away” from fossil fuels or for phasing them out or “down”.

Countries were considered to have expressed support if they explicitly mentioned the terms “transition” or “phase out/down” in relation to “fossil fuels” when speaking about their own actions to address climate change.

Some countries spoke in general terms about “reducing” or “replacing” fossil fuels, but did not explicitly reference the need to transition away from or phase them down or out. Others spoke about transitioning to a clean or renewable-based economy, but did not explicitly mention fossil fuels.

For the purposes of this analysis, all of these countries were considered to have not expressed support for the need to transition away from fossil fuels.

In addition, some countries mentioned in their NDCs that the global stocktake calls for a transition away from fossil fuels, but did not say that transitioning away from fossil fuels would be part of their own actions to address climate change.

These countries were also considered to have not expressed support for the need to transition away from fossil fuels.

Overall, the results show that only one-third of countries express support for the need to transition away from fossil fuels in their NDCs.

Countries used varying language when speaking about the need to transition away from fossil fuels.

Some directly acknowledged that transitioning away from fossil fuels was a key conclusion of the global stocktake and committed to doing this within their own borders.

This includes the UK, Brazil, Canada, Australia, Singapore, Lebanon and Niue. For example, the UK’s NDC states:

“At home and in line with the outcomes of the GST [global stocktake], the UK is committed to transitioning away from fossil fuels to achieve net-zero by 2050.”

Other countries chose to commit to “phasing out” fossil fuels instead of “transitioning away”.

This includes Iceland and Vanuatu. Similarly, Colombia’s NDC says:

“NDC 3.0 reaffirms that the phasing out of fossil fuels is not only a climate imperative, but also an opportunity to strengthen energy sovereignty [and] democratise the benefits of the transition.”

(Colombia and Vanuatu were two of the countries that were disappointed not to see a commitment to phase out fossil fuels included within the global stocktake text.)

Barbados, an island nation known for its strong commitment to climate action, committed in its NDC to “achieve a fossil fuel-free economy” by 2040. In addition, Chile pledged to contribute to the “elimination of fossil fuels”.

In the analysis, these pledges were considered to be support for transitioning away from fossil fuels, despite not using the terms “transition” or “phase out”.

The table below shows the language used by each of the 21 countries that expressed support for transitioning away from fossil fuels, according to the analysis.

decision 1/CMA.5, through the policies and national efforts below, including those under the

National Climate Plan. In addition, Brazil would welcome the launching of international work for

the definition of schedules for transitioning away from fossil fuels in energy systems, in a just,

orderly and equitable manner, with developed countries taking the lead, on the basis of the best

available science, reflecting equity and the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities

and respective capabilities in the light of different national circumstances and in the context of

sustainable development and efforts to eradicate poverty, as per paragraph 6 of decision 1/

CMA.5.”

(GST), agreed at COP28…This includes…transitioning away from fossil fuels in energy systems.”

the Plan for Global Warming Countermeasures, which is a comprehensive implementation plan for achieving Japan’s NDC.”

the government.”

In particular, we detail our domestic actions to contribute to the collective commitments

made following the global stocktake, including the tripling of renewable energy, doubling of

energy efficiency and removal of fossil fuel subsidies, all in pursuit of accelerating the

transition away from fossil fuels this decade.”

towards total electricity generation based on renewable sources, to transition away from fossil fuels toward cleaner, decentralised energy systems.”

Source: Carbon Brief analysis of UN NDC registry

Separately, the thinktank E3G has examined how countries speak about their policies for reducing fossil fuels in their NDCs.

It found that more than two-thirds of countries include “explicit references to displacing fossil fuels in their electricity mix”.

However, E3G also noted that “specific language on winding down the production of coal, oil, and fossil gas is lacking in almost all NDCs”.

‘Transitional fuel’

Carbon Brief also examined each of the submitted NDCs to see how countries speak about new fossil-fuel production and use within their borders.

Six of the 64 nations – around 10% – used their NDCs to pledge to increase fossil-fuel production or use, predominately gas, claiming this could contribute to their efforts to lower emissions.

In its NDC, the world’s fourth biggest emitter, Russia, says it “emphasises the importance of implementing a just transition to low-emission development models using all available solutions”, including “gas as a transition fuel and technologies for reducing emissions in coal-fired power generation”.

During negotiations on the stocktake text in 2023, Russia had pushed successfully to include a controversial paragraph that says “transitional fuels can play a role in facilitating the energy transition while ensuring energy security”, Climate Home News reported.

The publication noted that, after this text was agreed, Antigua and Barbuda negotiator Diann Black-Layne called it a “dangerous loophole”, adding that gas is also a fossil fuel that “we need to transition away from”.

Several African nations, including Nigeria, Morocco, Mauritius and Zimbabwe, also pledged to boost the production or use of gas as part of their “climate” actions.

Nigeria, Africa’s second biggest emitter, says that the country “relies heavily on the oil and gas industry” and that the sector will be “called upon to further grow while adopting sustainability measures”. It continues:

“Natural gas use will be boosted, serving as a key transition fuel in Nigeria’s move towards increased adoption of renewable energy for meeting its net-zero emissions target.”

The world’s energy watchdog, the International Energy Agency, recently reemphasised that there would be no need for any new fossil-fuel production, if the world cuts emissions in line with limiting global warming to 1.5C.

It comes after the world’s top court this year concluded that new fossil-fuel production, consumption, the granting of exploration licences or the provision of subsidies “may constitute an internationally wrongful act”, leaving the states involved vulnerable to legal action.

COP30 calls

After nearly all nations missed the deadline for submitting NDCs in February, UN climate chief Simon Stiell asked laggard countries to do so by the end of September.

This will allow their plans to be included in a new report synthesising the level of progress contained within the latest NDCs, which is due to be published on 24 October. (Less than a third of nations met Stiell’s request.)

The report will come just before COP30, which will take place from 10-21 November in the rainforest Brazilian city of Belém.

Whether and how to respond to the insufficient progress contained within these NDCs, including whether to call for increased ambition in line with the outcomes of the first global stocktake, are among the key issues up for debate at the summit.

The Brazilian presidency is pushing for a formal COP decision on any “disappoint[ment]” over NDCs falling short, collectively, of what is needed to avoid dangerous global warming.

However, other countries would need to agree to this proposal at the summit.