After the shock of her husband’s death by suicide, Trudy Meehan’s biggest concern was how she would support their two-year-old daughter, Meara.

“There’s obviously grief and shock and — with death through suicide — the stigma that’s still around, the guilt,” Meehan says. “And ours wasn’t the usual story: Our relationship had broken up, and he died after that. A relationship break-up is a big trigger for suicide,” says Wexford-based Meehan, who sees a lot of talk about suicide prevention, but not much about the people left behind.

“We need to have more public [conversations] about the impact on family,” she says, pointing to a survey of people bereaved by suicide in Ireland.

“It shows people never stop asking ‘why?’, and that we need resources in the community to help people talk about bereavement by suicide.”

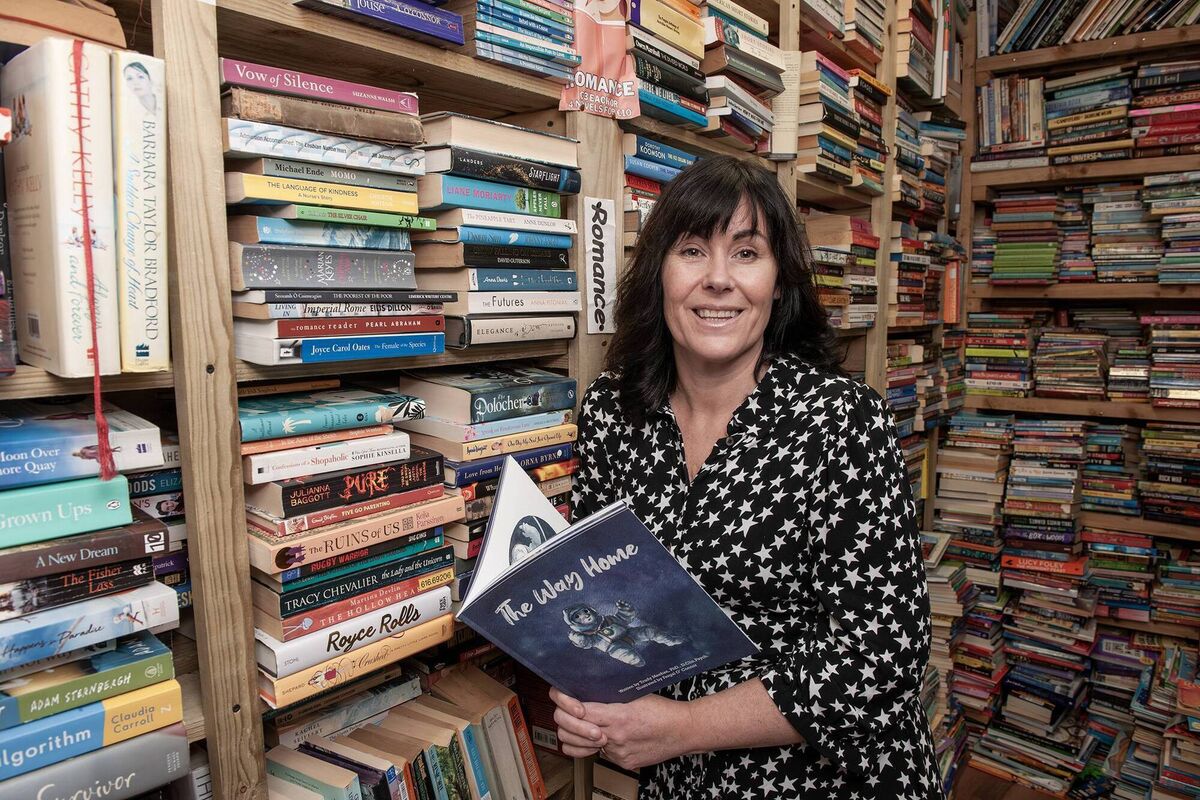

Trudy Meehan pictured in Red Books, Wexford town. Pic: Jim Campbell

Trudy Meehan pictured in Red Books, Wexford town. Pic: Jim Campbell

The Way Home, by Trudy Meehan

The Way Home, by Trudy Meehan

- Be honest, but keep it appropriate for the child’s age and development. Be concrete. Don’t use euphemisms (say ‘dead’, not ‘gone to sleep’). It’s OK to say, ‘I don’t know the answer to that’, or ‘I don’t have the right words to explain that to you, but I promise I’ll find them and come back to answer your question’.

- With growth and maturity, children’s understanding of death increases — they may need to revisit their grief over the years. It’s natural for them to try to understand the loss when they’ve developed a better ability to do so.

-

Follow the child’s lead, but offer openings for them to talk — the adult provides space and opportunity, the child decides if they take the opportunity, and when to end. Remember:

Children may process through movement, play, song, dance, art, making or breaking things, or feeling physical pain. Conversations or processing are often very short and momentary — go with their flow.