Economists say house price growth in 2026 is likely to stay muted. Would that be such a bad thing, writes Catherine McGregor in today’s extract from The Bulletin.

To receive The Bulletin in full each weekday, sign up here.

Fixed rates near the bottom of the cycle

The Reserve Bank’s 25-basis-point cut this week – taking the OCR to 2.25% – immediately flowed through to floating and flexible home loan rates. But for fixed-term borrowers, the effect is more muted. Markets had fully priced in the move, and economists now believe the downtrend in mortgage rates is close to bottoming out. Swap rates even lifted slightly after the announcement, signalling limited room for further drops unless the economic outlook worsens.

BNZ chief economist Mike Jones told RNZ the downtrend in fixed rates “was on its last legs anyway”, with the Reserve Bank’s shift toward a more neutral stance reducing the chances of further significant falls. Longer fixes, such as five-year rates, may already be at or near their lowest. Analysts from Kiwibank, Infometrics and ANZ expect the next phase of the rate cycle to be stability rather than continued declines, with gentle increases possible from mid-2026.

Supply glut limits impact on house prices

The OCR cut is expected to ease mortgage pressure but not to drive any near-term increase in house prices. A surge in new listings through October and November pushed total stock back towards its peak level for the year, giving buyers more choice and reducing urgency. In commentary republished in Newsroom, BNZ’s Jones said new listings growth “continues to nullify any pressure on house prices to rise and is in contrast to expectations the inventory overhang would be worked off this year”.

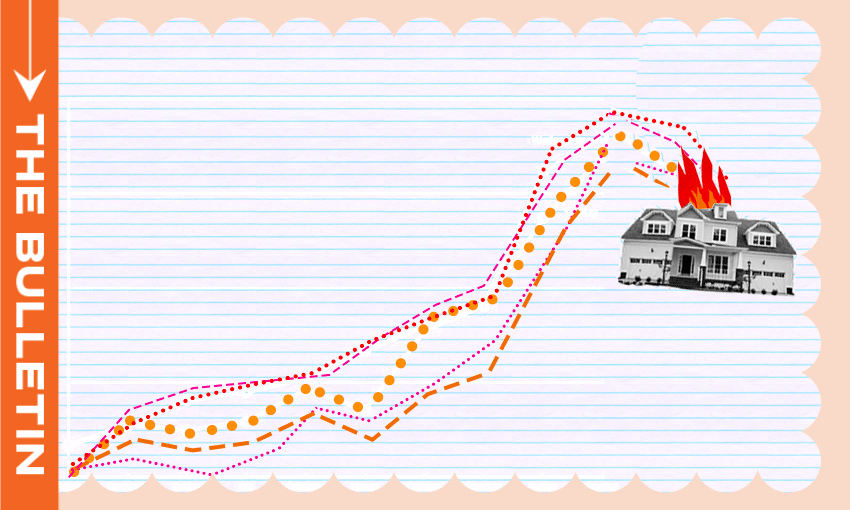

Nationally, prices remain nearly flat, with slight monthly fluctuations but no consistent momentum. Looking to 2026, most forecasters, including the Reserve Bank, expect modest growth of around 4%. The reasons for an increase, however small, include a small recovery in population growth, mortgage rates staying low, and the broader economy slowly regaining traction. However, as in the last few months, high numbers of listings are expected to keep price rises contained.

Should we want higher prices?

Forecasts for price increases are often treated as a positive, with this week’s story on the NZ house market by Reuters’ Lucy Craymer finding deep anxiety about the end of automatic capital gains. After the boom-and-bust cycle of the past few years – including a 40% Covid-era surge followed by falls of up to 30% in some cities – the downturn has “had a chilling effect on consumption and the economy”, Craymer reports. With more than half of New Zealand’s household wealth tied up in property, that shift in sentiment has been powerful, she wrote.

But there is increasing pushback against the assumption that rising prices stimulate the economy. The NZ Herald’s Liam Dann (paywalled) recently highlighted Motu research showing that most households actually spend less when property prices rise, as mortgages or rents grow alongside them. Only outright owners tend to spend more. As Dann wrote, “Locally, at least, the Motu data effectively negates the last remaining argument for a housing market boom, even as a short-term economic panacea.”

Pushing back against the ‘wealth effect’

That broader rethink was also the focus of Hayden Donnell’s piece in The Spinoff skewering the belief – still echoed by politicians including prime minister Christopher Luxon – that rising property values are something to be encouraged. Donnell cited Infometrics forecaster Gareth Kiernan, who argued the wealth effect may be a “correlation causation error”, with confidence driven by other factors such as low unemployment rather than house prices themselves. And even if homeowners do feel richer, Donnell warned, that confidence “may be a double-edged sword, worsening the shock when the economy turns and homeowners find themselves with a declining property asset and ongoing debt repayments to make on their stupid new speedboat”.

The deeper problem, Donnell concluded, is that the ostensible wealth effect leaves so many people behind. Any benefit to homeowners, he wrote, “tends to come with a corresponding ‘I’m on the bones of my arse’ effect for those who don’t own homes.”

Subscribe to +Subscribe